Researchers harness 2D magnetic materials for energy-efficient computing

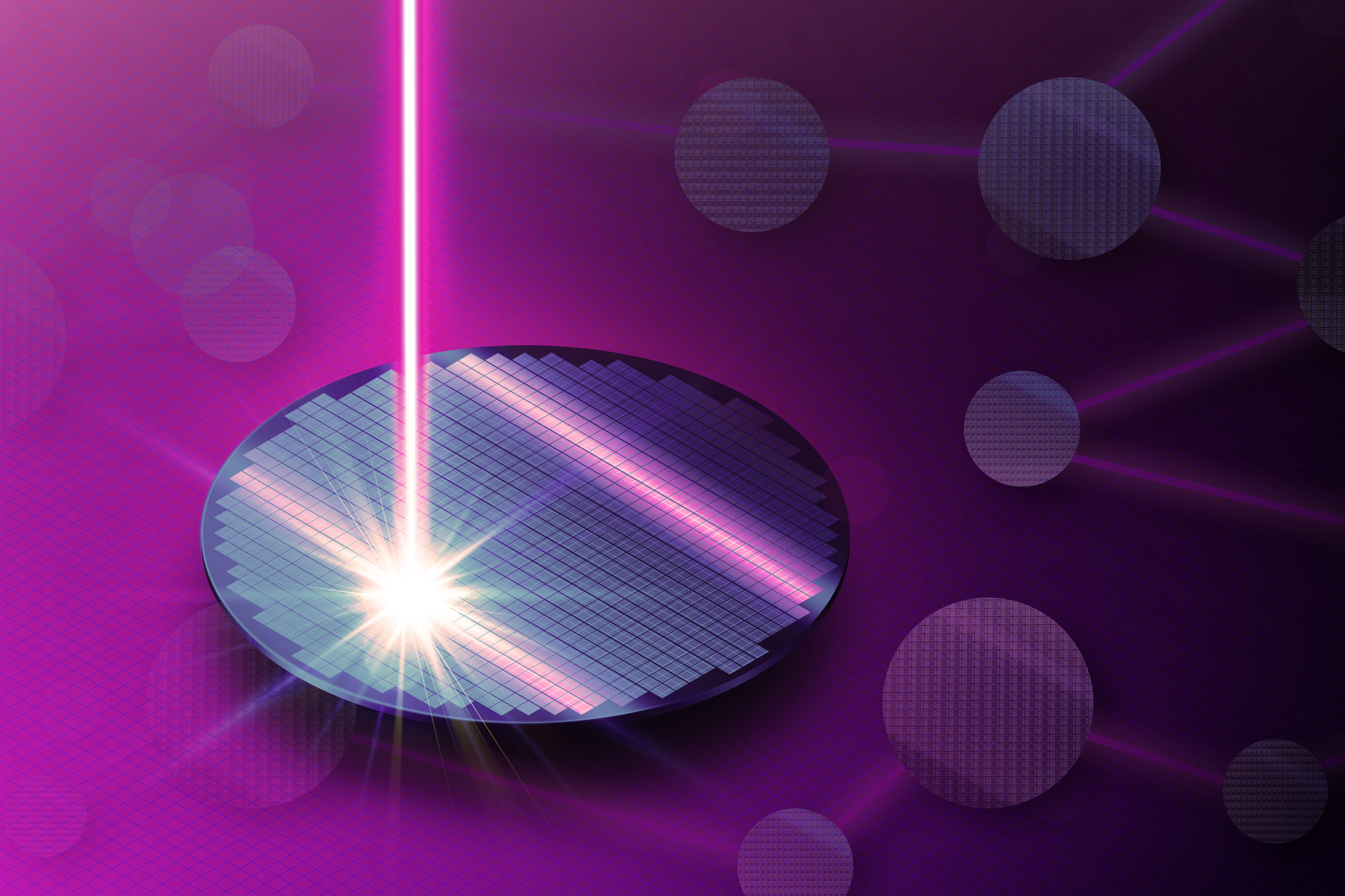

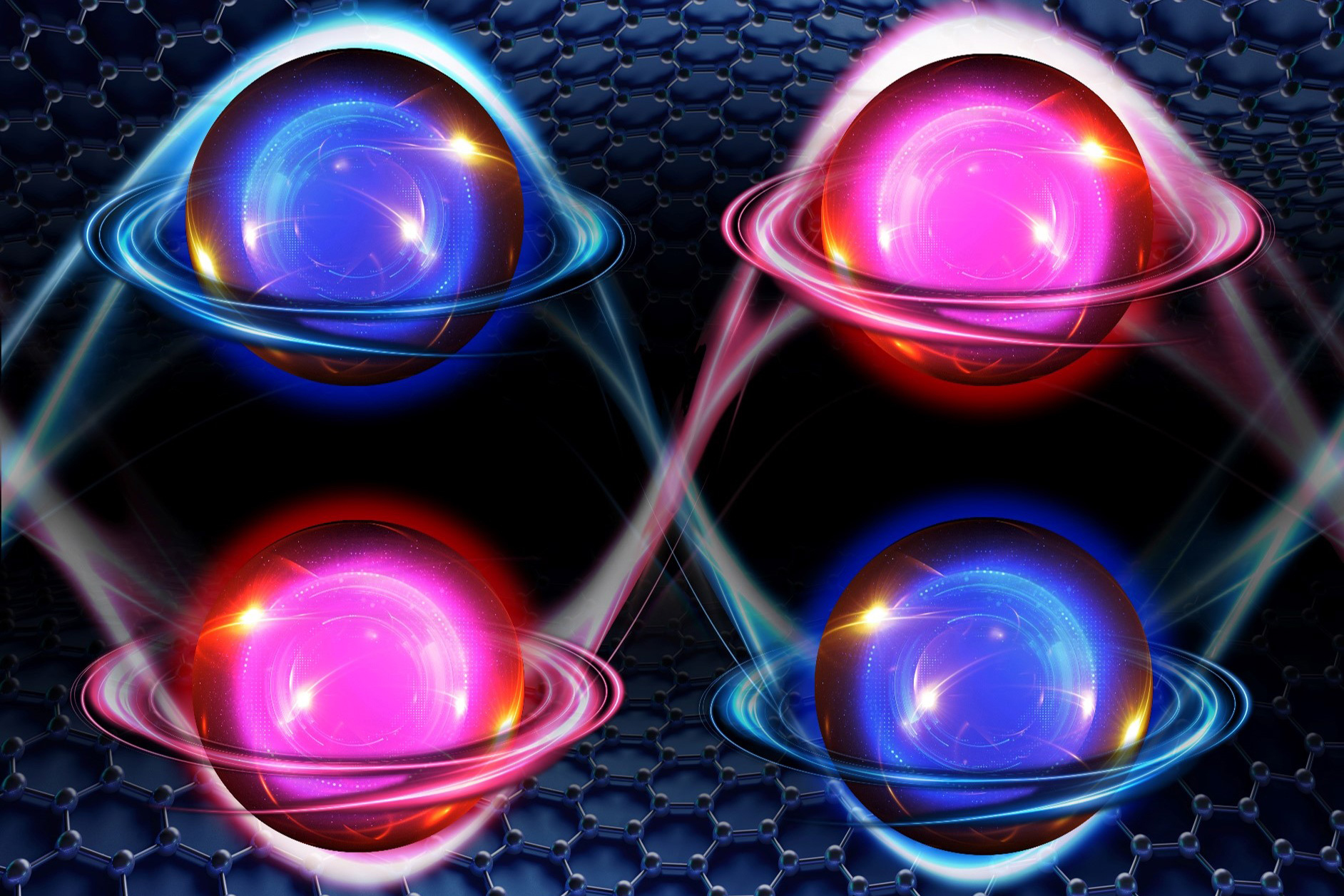

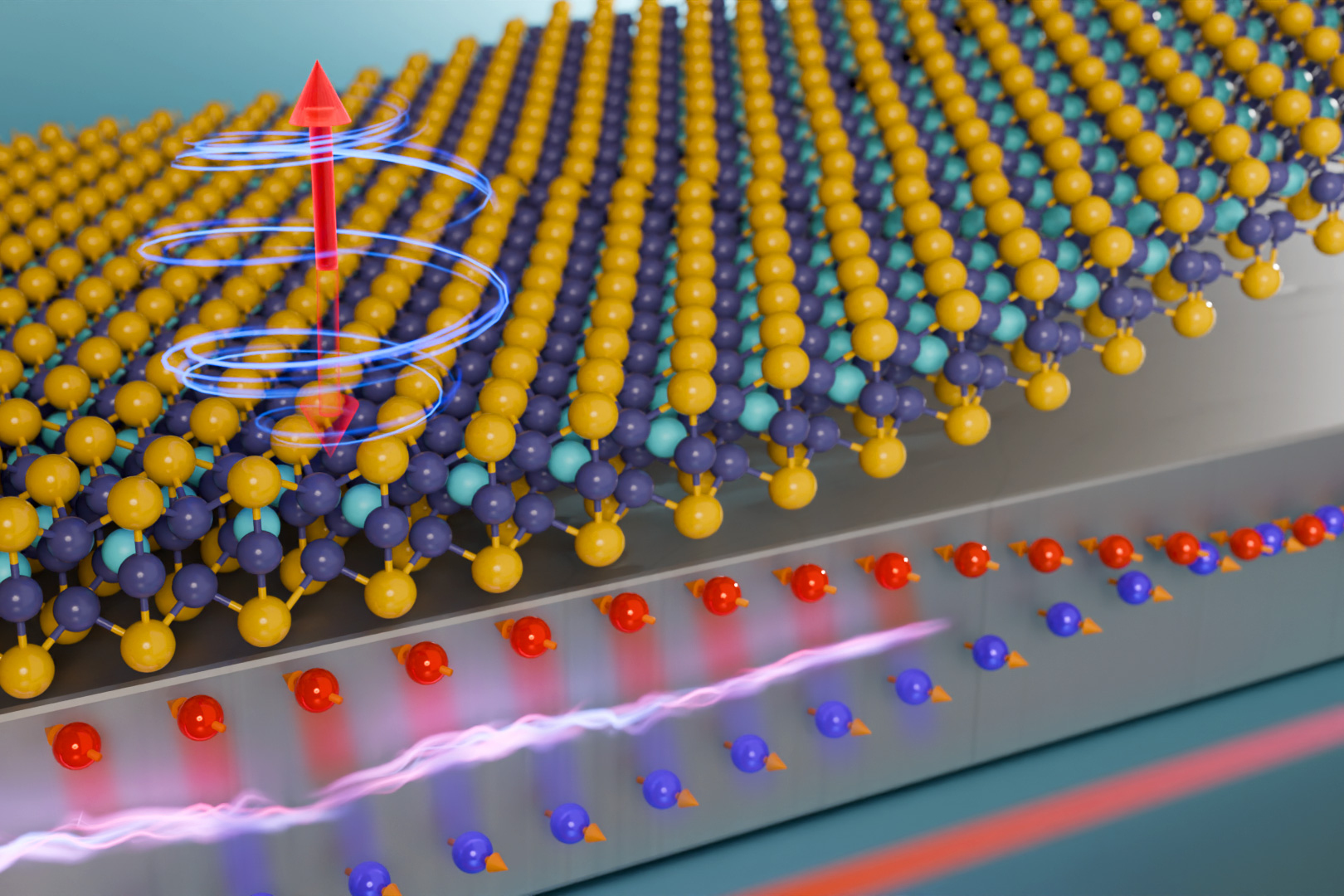

Experimental computer memories and processors built from magnetic materials use far less energy than traditional silicon-based devices. Two-dimensional magnetic materials, composed of layers that are only a few atoms thick, have incredible properties that could allow magnetic-based devices to achieve unprecedented speed, efficiency, and scalability.

While many hurdles must be overcome until these so-called van der Waals magnetic materials can be integrated into functioning computers, MIT researchers took an important step in this direction by demonstrating precise control of a van der Waals magnet at room temperature.

This is key, since magnets composed of atomically thin van der Waals materials can typically only be controlled at extremely cold temperatures, making them difficult to deploy outside a laboratory.

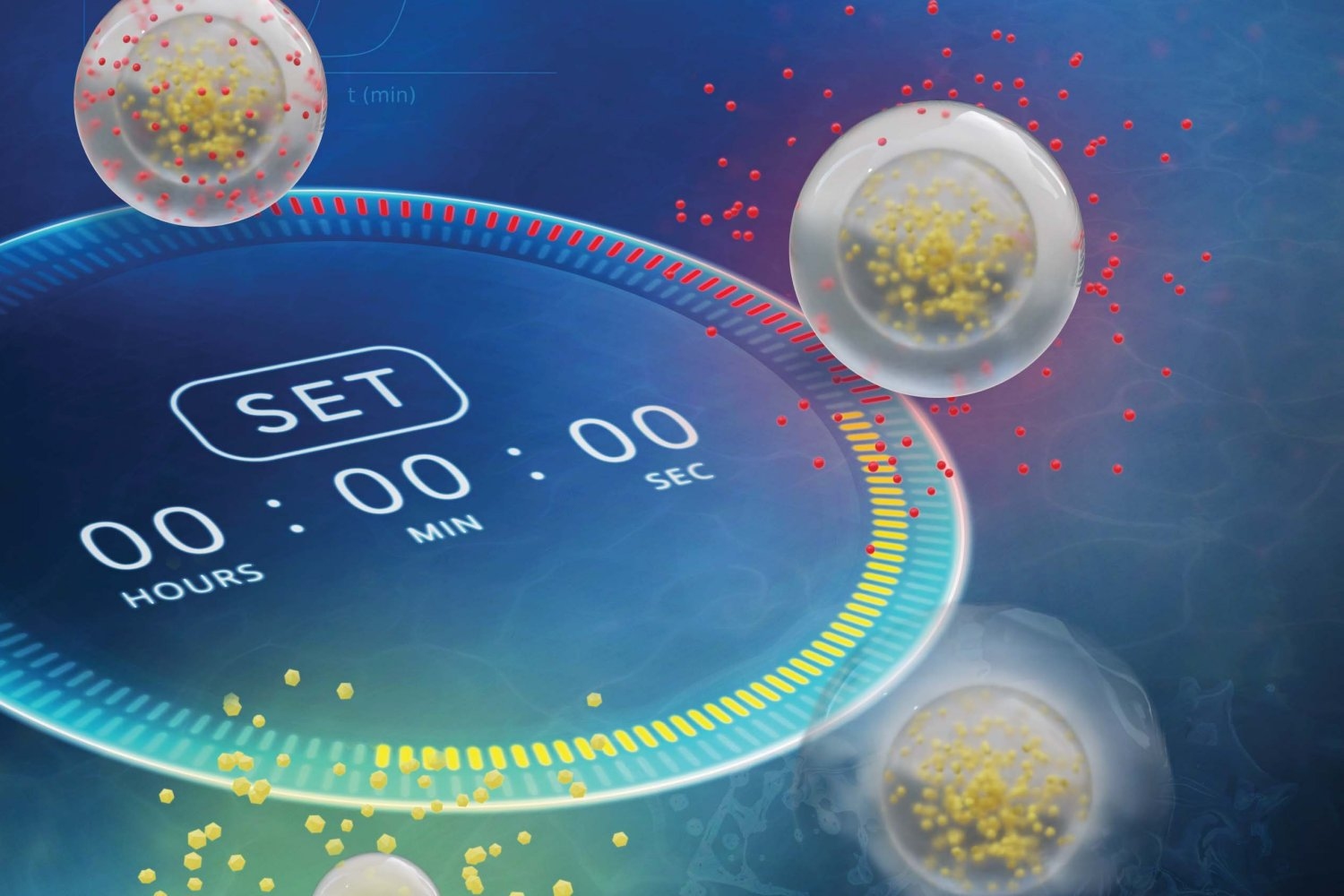

The researchers used pulses of electrical current to switch the direction of the device’s magnetization at room temperature. Magnetic switching can be used in computation, the same way a transistor switches between open and closed to represent 0s and 1s in binary code, or in computer memory, where switching enables data storage.

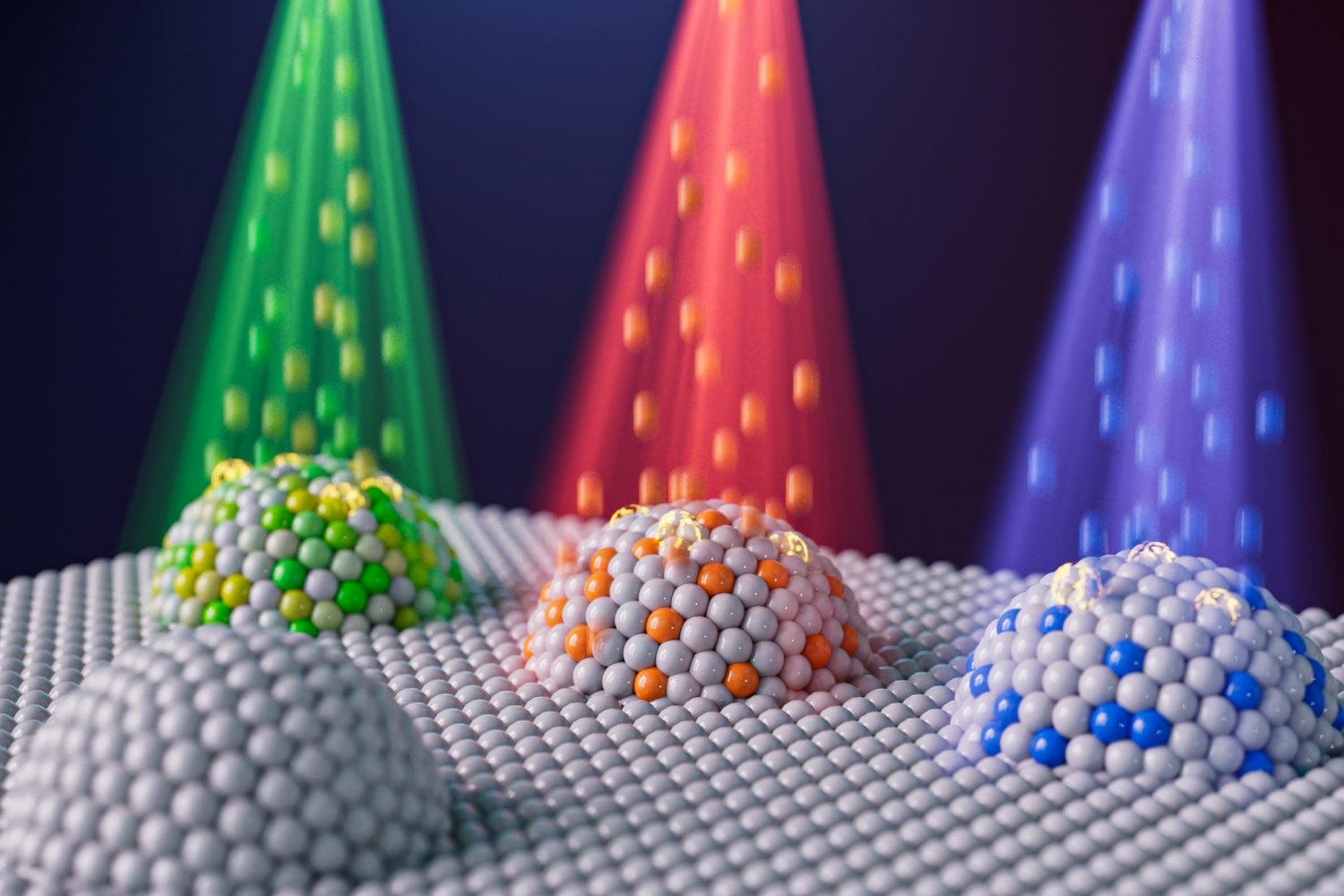

The team fired bursts of electrons at a magnet made of a new material that can sustain its magnetism at higher temperatures. The experiment leveraged a fundamental property of electrons known as spin, which makes the electrons behave like tiny magnets. By manipulating the spin of electrons that strike the device, the researchers can switch its magnetization.

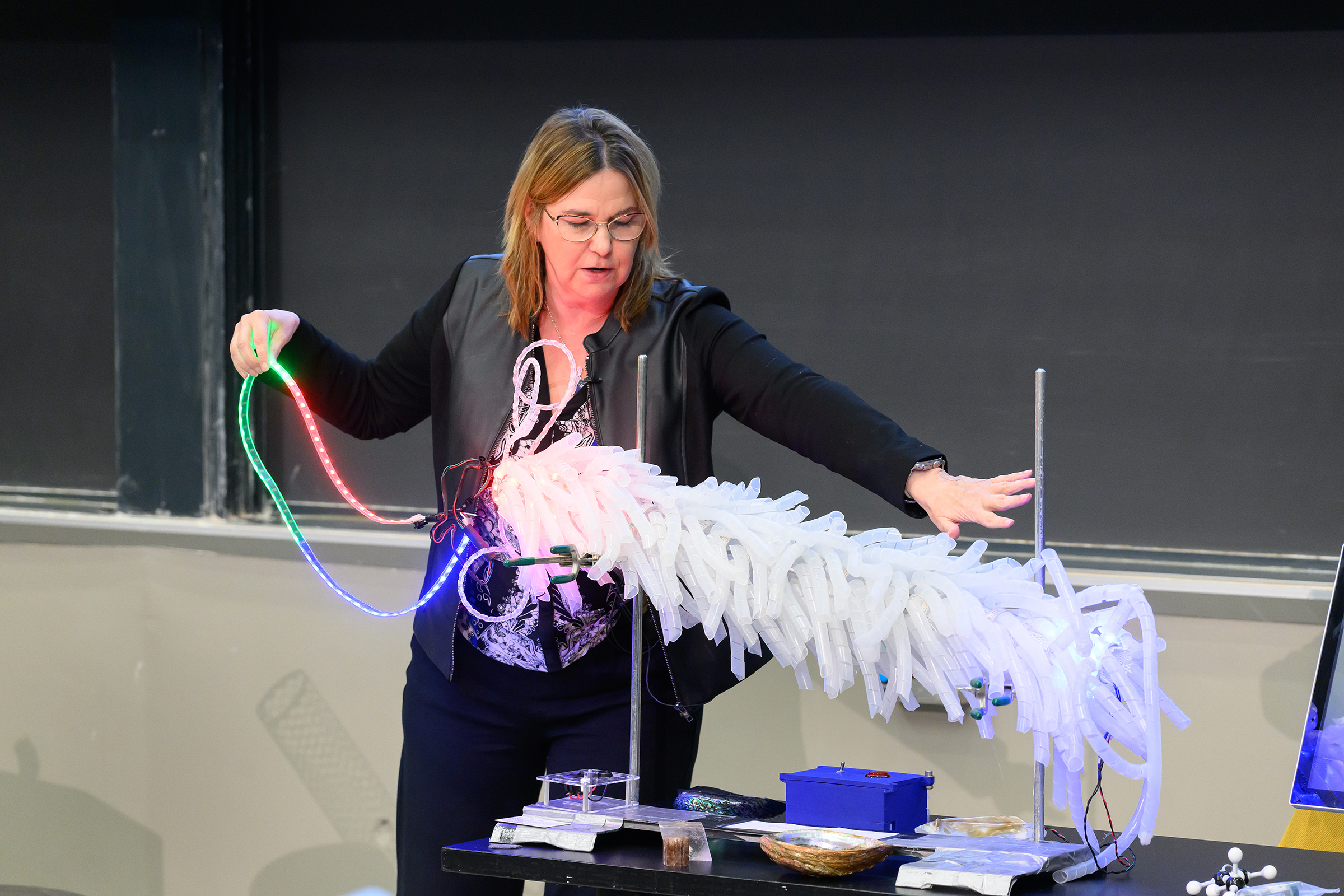

“The heterostructure device we have developed requires an order of magnitude lower electrical current to switch the van der Waals magnet, compared to that required for bulk magnetic devices,” says Deblina Sarkar, the AT&T Career Development Assistant Professor in the MIT Media Lab and Center for Neurobiological Engineering, head of the Nano-Cybernetic Biotrek Lab, and the senior author of a paper on this technique. “Our device is also more energy efficient than other van der Waals magnets that are unable to switch at room temperature.”

In the future, such a magnet could be used to build faster computers that consume less electricity. It could also enable magnetic computer memories that are nonvolatile, which means they don’t leak information when powered off, or processors that make complex AI algorithms more energy-efficient.

“There is a lot of inertia around trying to improve materials that worked well in the past. But we have shown that if you make radical changes, starting by rethinking the materials you are using, you can potentially get much better solutions,” says Shivam Kajale, a graduate student in Sarkar’s lab and co-lead author of the paper.

Kajale and Sarkar are joined on the paper by co-lead author Thanh Nguyen, a graduate student in the Department of Nuclear Science and Engineering (NSE); Corson Chao, a graduate student in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering (DSME); David Bono, a DSME research scientist; Artittaya Boonkird, an NSE graduate student; and Mingda Li, associate professor of nuclear science and engineering. The research appears this week in Nature Communications.

An atomically thin advantage

Methods to fabricate tiny computer chips in a clean room from bulk materials like silicon can hamper devices. For instance, the layers of material may be barely 1 nanometer thick, so minuscule rough spots on the surface can be severe enough to degrade performance.

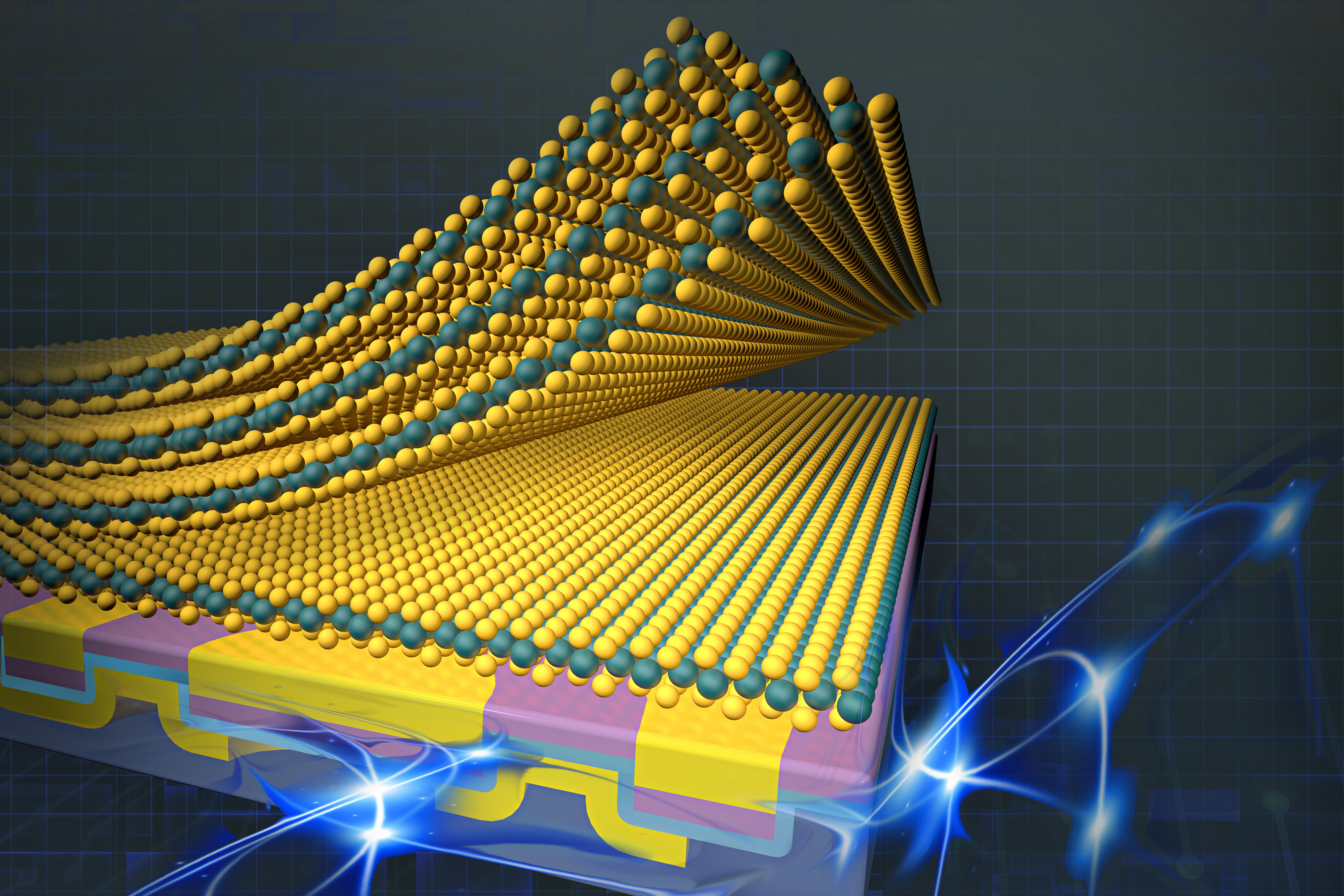

By contrast, van der Waals magnetic materials are intrinsically layered and structured in such a way that the surface remains perfectly smooth, even as researchers peel off layers to make thinner devices. In addition, atoms in one layer won’t leak into other layers, enabling the materials to retain their unique properties when stacked in devices.

“In terms of scaling and making these magnetic devices competitive for commercial applications, van der Waals materials are the way to go,” Kajale says.

But there’s a catch. This new class of magnetic materials have typically only been operated at temperatures below 60 kelvins (-351 degrees Fahrenheit). To build a magnetic computer processor or memory, researchers need to use electrical current to operate the magnet at room temperature.

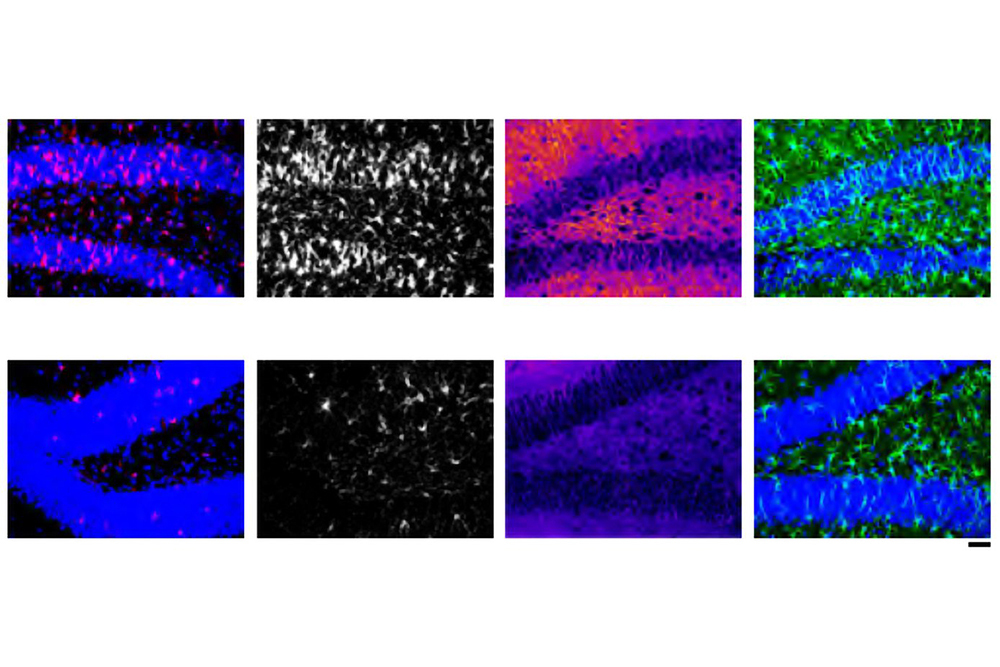

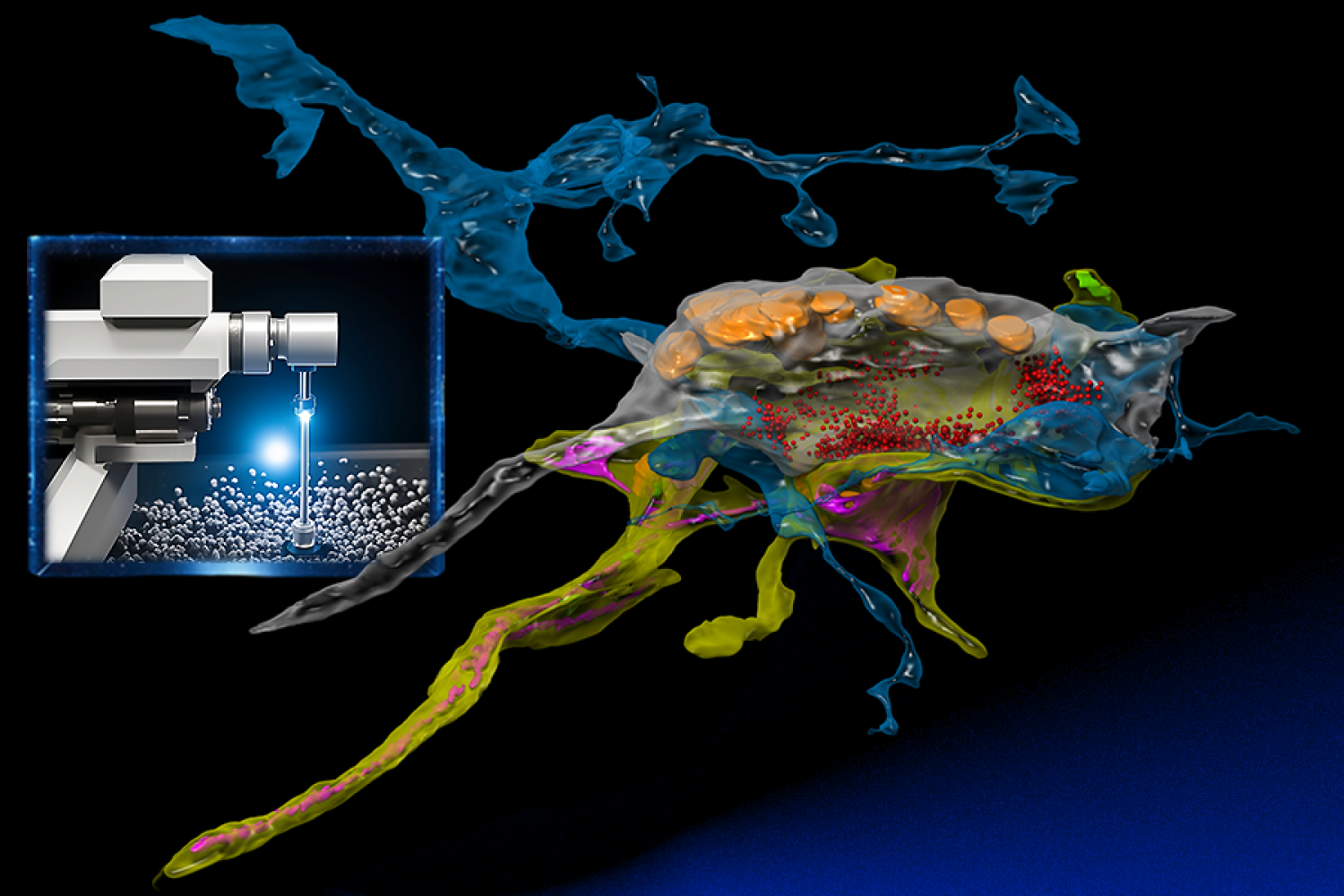

To achieve this, the team focused on an emerging material called iron gallium telluride. This atomically thin material has all the properties needed for effective room temperature magnetism and doesn’t contain rare earth elements, which are undesirable because extracting them is especially destructive to the environment.

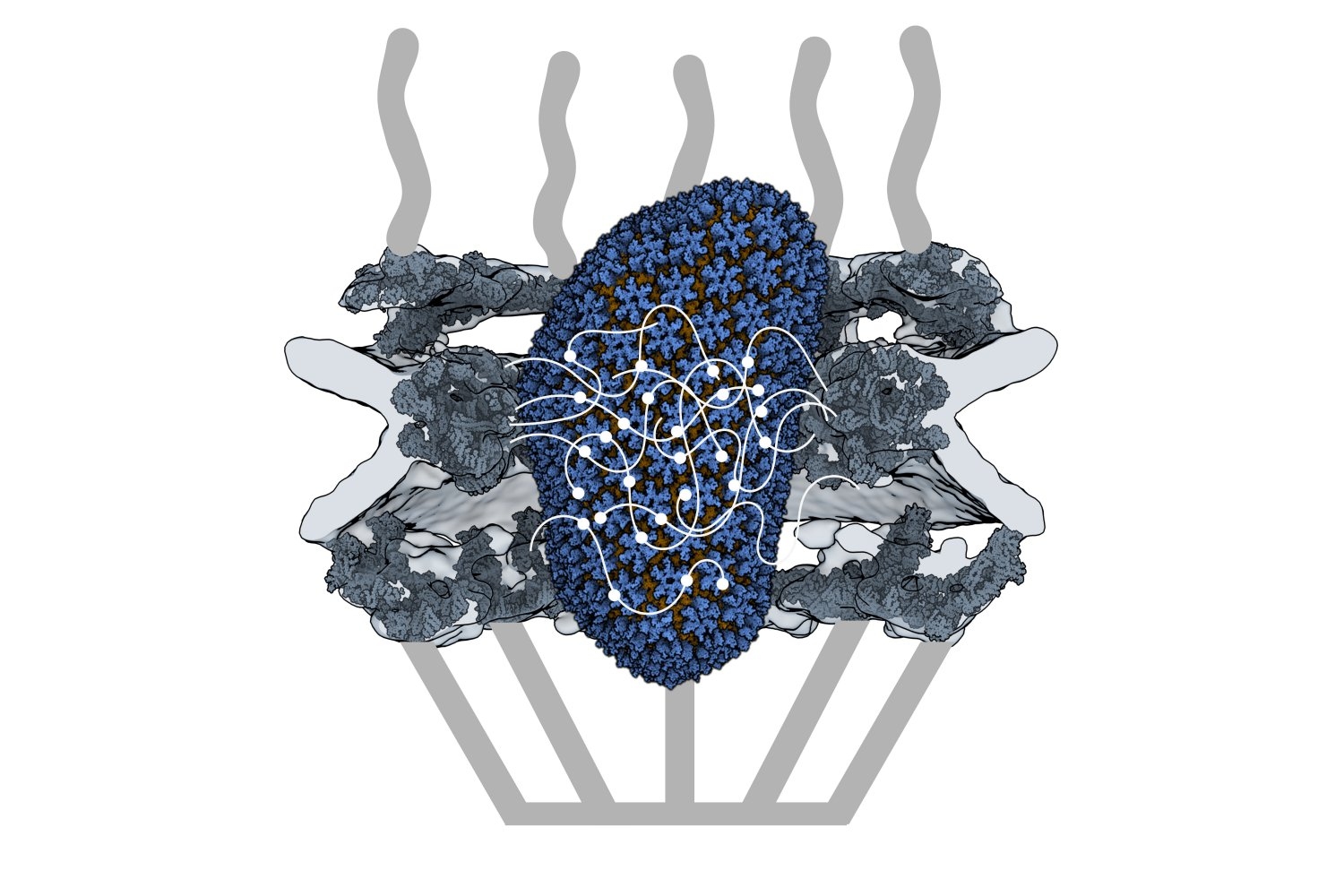

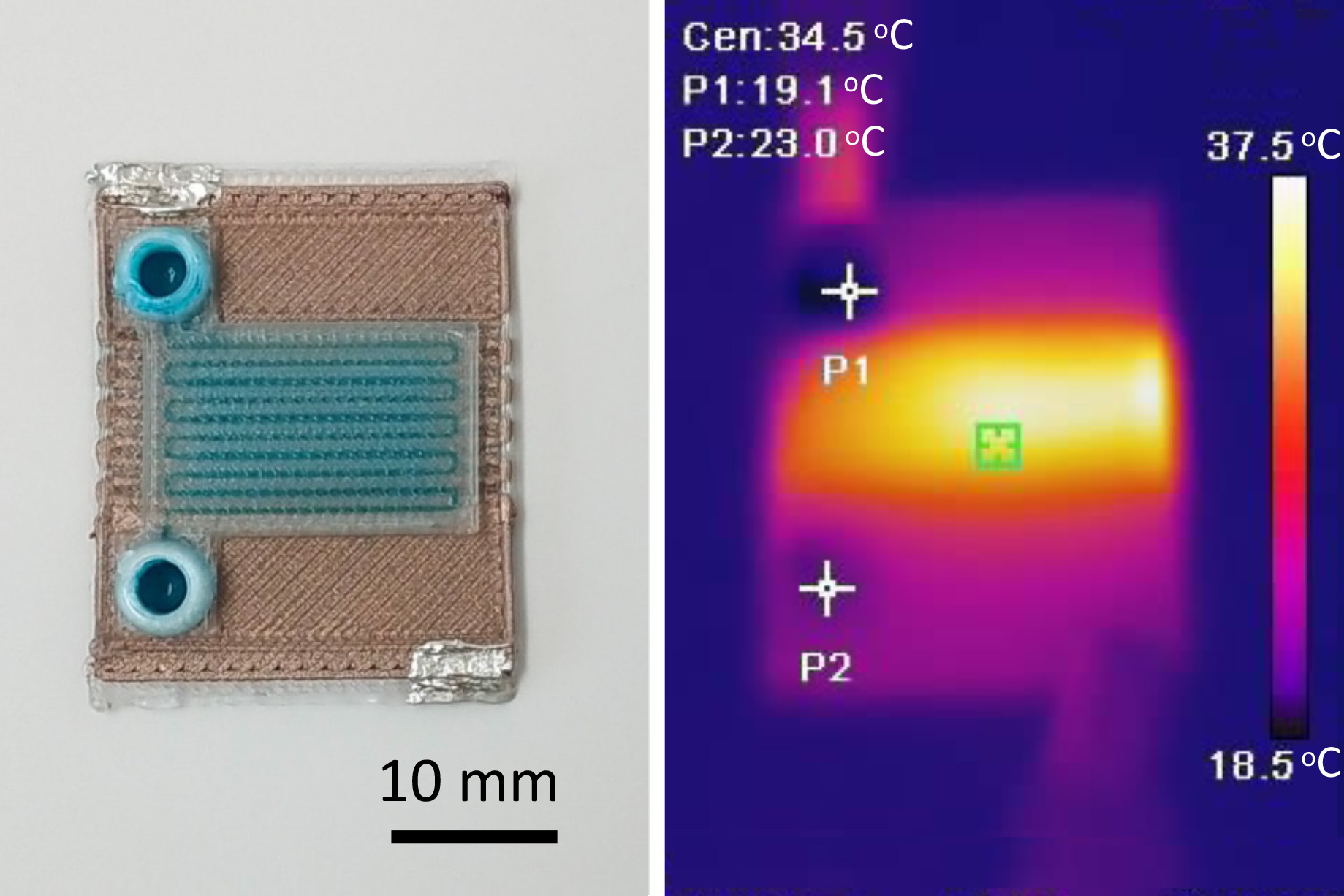

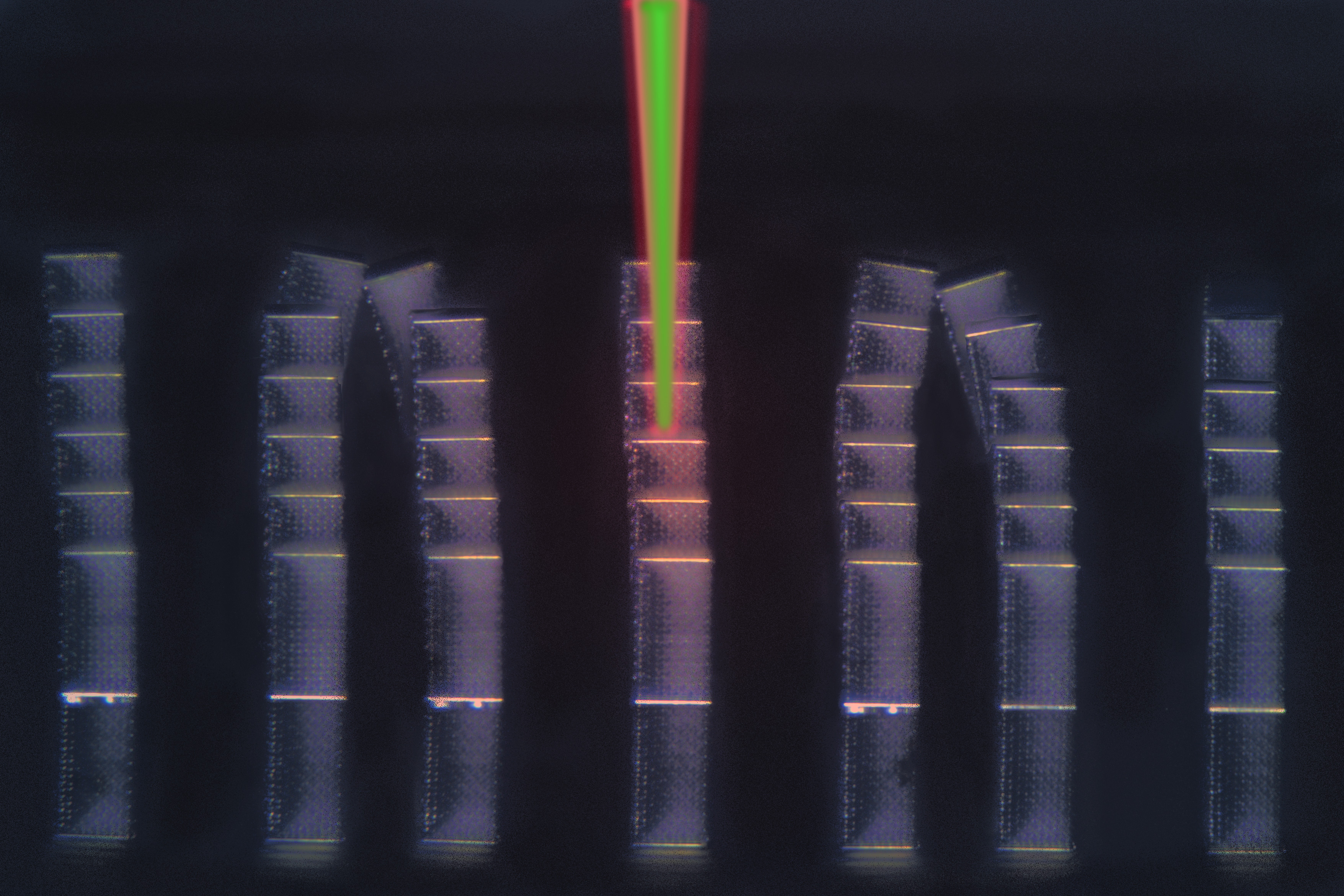

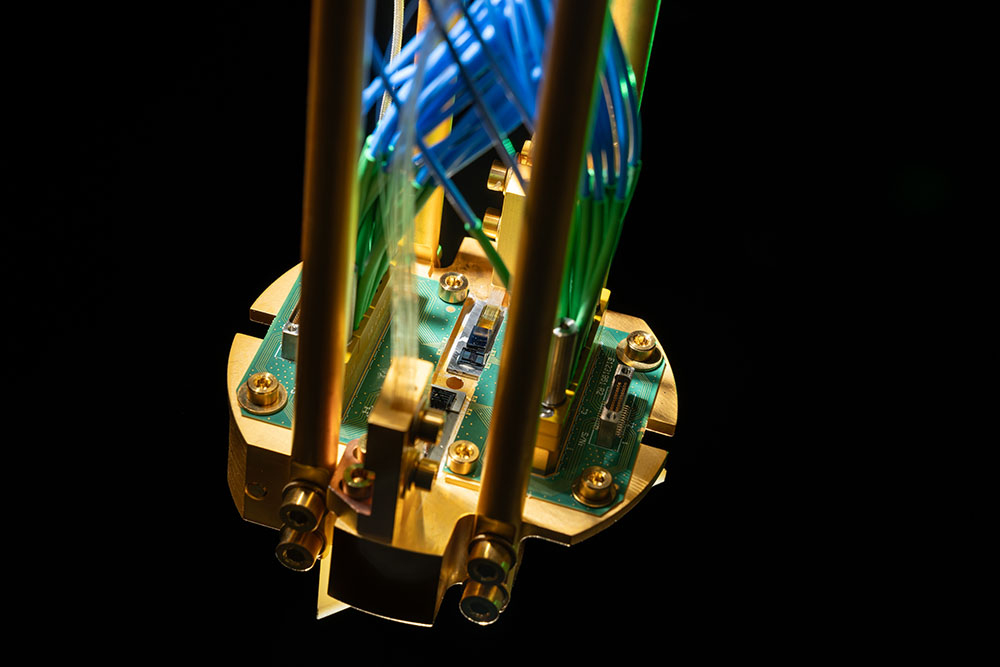

Nguyen carefully grew bulk crystals of this 2D material using a special technique. Then, Kajale fabricated a two-layer magnetic device using nanoscale flakes of iron gallium telluride underneath a six-nanometer layer of platinum.

Tiny device in hand, they used an intrinsic property of electrons known as spin to switch its magnetization at room temperature.

Electron ping-pong

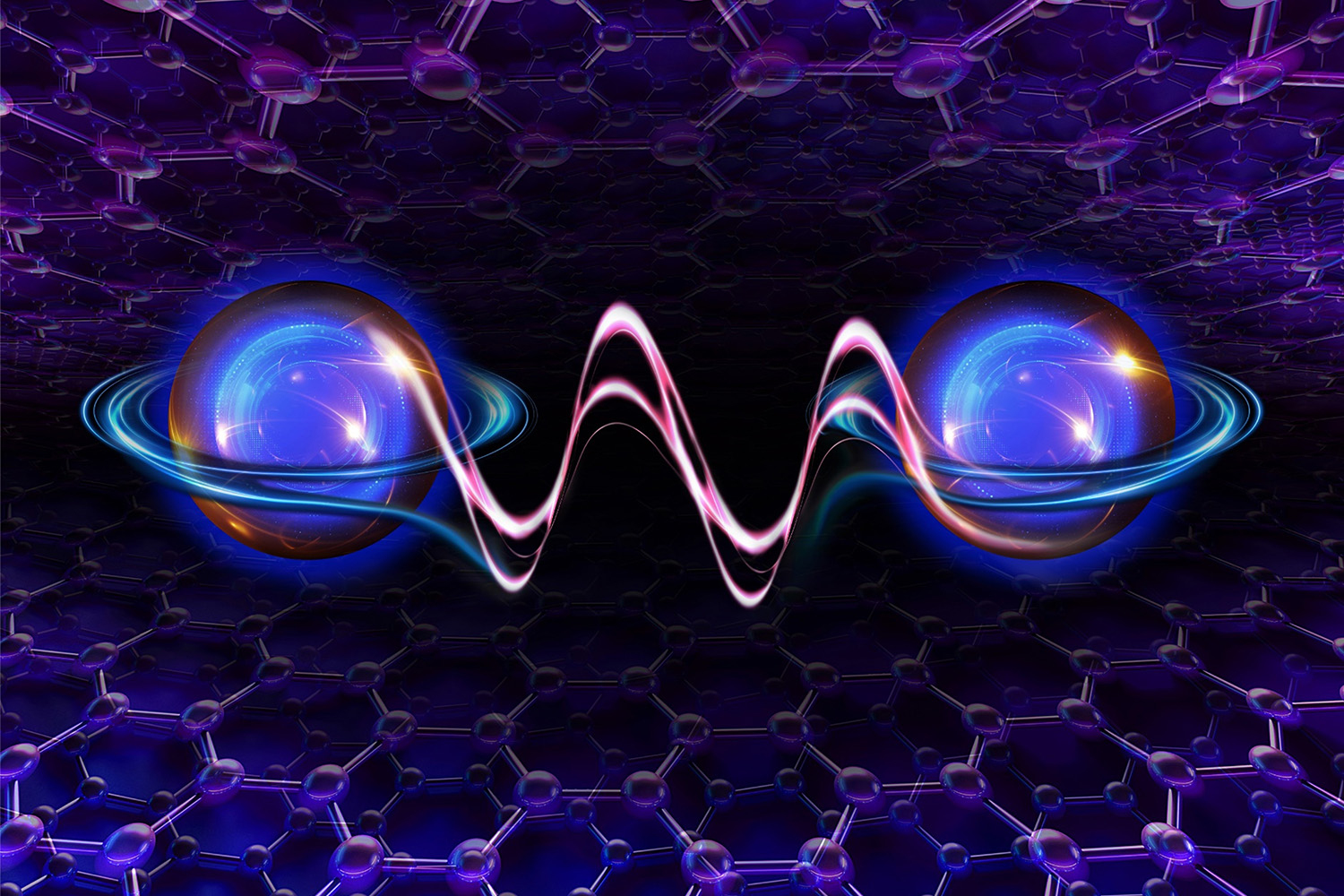

While electrons don’t technically “spin” like a top, they do possess the same kind of angular momentum. That spin has a direction, either up or down. The researchers can leverage a property known as spin-orbit coupling to control the spins of electrons they fire at the magnet.

The same way momentum is transferred when one ball hits another, electrons will transfer their “spin momentum” to the 2D magnetic material when they strike it. Depending on the direction of their spins, that momentum transfer can reverse the magnetization.

In a sense, this transfer rotates the magnetization from up to down (or vice-versa), so it is called a “torque,” as in spin-orbit torque switching. Applying a negative electric pulse causes the magnetization to go downward, while a positive pulse causes it to go upward.

The researchers can do this switching at room temperature for two reasons: the special properties of iron gallium telluride and the fact that their technique uses small amounts of electrical current. Pumping too much current into the device would cause it to overheat and demagnetize.

The team faced many challenges over the two years it took to achieve this milestone, Kajale says. Finding the right magnetic material was only half the battle. Since iron gallium telluride oxidizes quickly, fabrication must be done inside a glovebox filled with nitrogen.

“The device is only exposed to air for 10 or 15 seconds, but even after that I have to do a step where I polish it to remove any oxide,” he says.

Now that they have demonstrated room-temperature switching and greater energy efficiency, the researchers plan to keep pushing the performance of magnetic van der Waals materials.

“Our next milestone is to achieve switching without the need for any external magnetic fields. Our aim is to enhance our technology and scale up to bring the versatility of van der Waals magnet to commercial applications,” Sarkar says.

This work was carried out, in part, using the facilities at MIT.Nano and the Harvard University Center for Nanoscale Systems.

© Image: Courtesy of the researchers