AMD’s Zen 5 is a missed opportunity in messaging

Last week AMD did their 'Tech Day' and it was anything but.

Read more ▶

The post AMD’s Zen 5 is a missed opportunity in messaging appeared first on SemiAccurate.

Last week AMD did their 'Tech Day' and it was anything but.

Read more ▶

The post AMD’s Zen 5 is a missed opportunity in messaging appeared first on SemiAccurate.

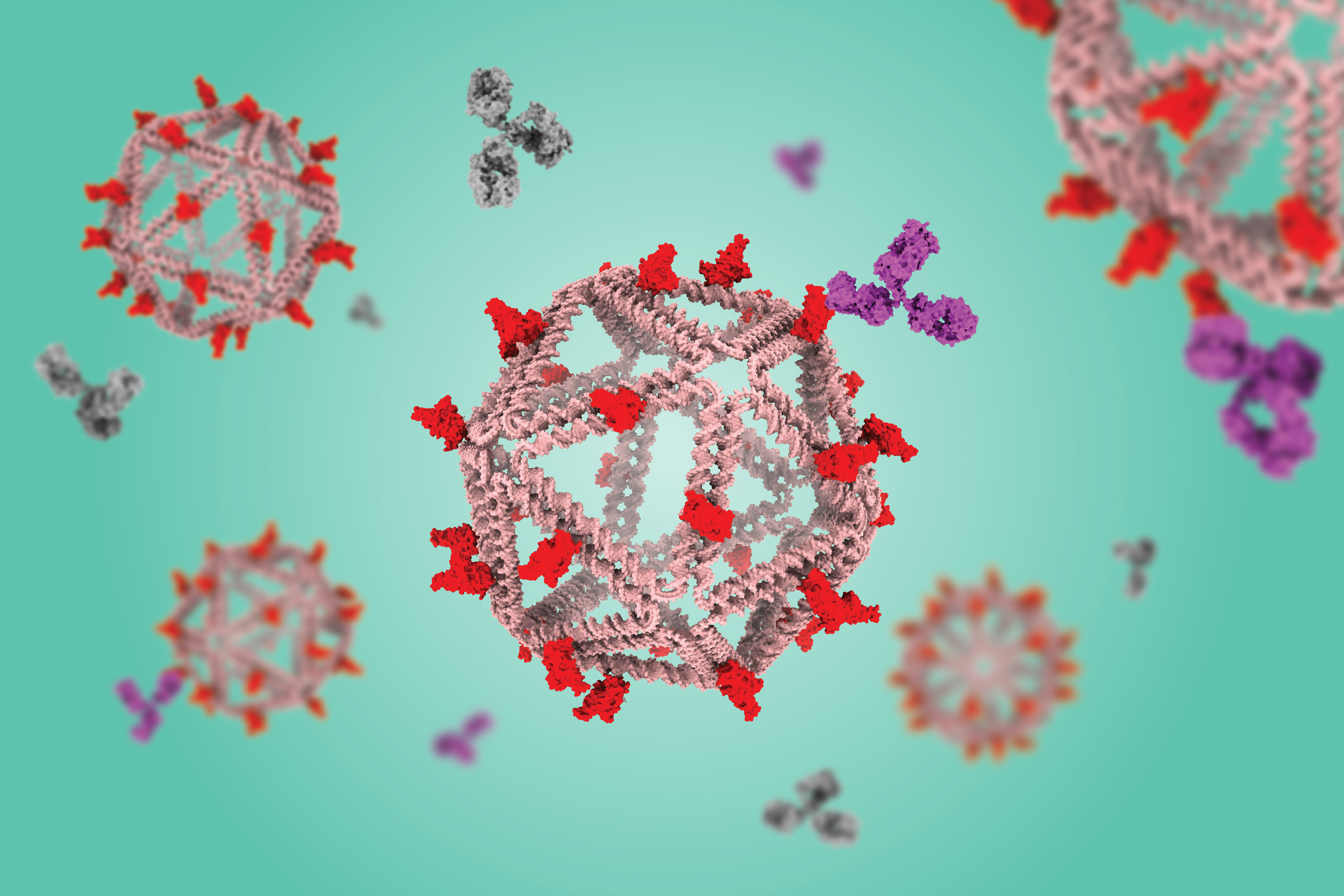

Using a virus-like delivery particle made from DNA, researchers from MIT and the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard have created a vaccine that can induce a strong antibody response against SARS-CoV-2.

The vaccine, which has been tested in mice, consists of a DNA scaffold that carries many copies of a viral antigen. This type of vaccine, known as a particulate vaccine, mimics the structure of a virus. Most previous work on particulate vaccines has relied on protein scaffolds, but the proteins used in those vaccines tend to generate an unnecessary immune response that can distract the immune system from the target.

In the mouse study, the researchers found that the DNA scaffold does not induce an immune response, allowing the immune system to focus its antibody response on the target antigen.

“DNA, we found in this work, does not elicit antibodies that may distract away from the protein of interest,” says Mark Bathe, an MIT professor of biological engineering. “What you can imagine is that your B cells and immune system are being fully trained by that target antigen, and that’s what you want — for your immune system to be laser-focused on the antigen of interest.”

This approach, which strongly stimulates B cells (the cells that produce antibodies), could make it easier to develop vaccines against viruses that have been difficult to target, including HIV and influenza, as well as SARS-CoV-2, the researchers say. Unlike T cells, which are stimulated by other types of vaccines, these B cells can persist for decades, offering long-term protection.

“We’re interested in exploring whether we can teach the immune system to deliver higher levels of immunity against pathogens that resist conventional vaccine approaches, like flu, HIV, and SARS-CoV-2,” says Daniel Lingwood, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School and a principal investigator at the Ragon Institute. “This idea of decoupling the response against the target antigen from the platform itself is a potentially powerful immunological trick that one can now bring to bear to help those immunological targeting decisions move in a direction that is more focused.”

Bathe, Lingwood, and Aaron Schmidt, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School and principal investigator at the Ragon Institute, are the senior authors of the paper, which appears today in Nature Communications. The paper’s lead authors are Eike-Christian Wamhoff, a former MIT postdoc; Larance Ronsard, a Ragon Institute postdoc; Jared Feldman, a former Harvard University graduate student; Grant Knappe, an MIT graduate student; and Blake Hauser, a former Harvard graduate student.

Mimicking viruses

Particulate vaccines usually consist of a protein nanoparticle, similar in structure to a virus, that can carry many copies of a viral antigen. This high density of antigens can lead to a stronger immune response than traditional vaccines because the body sees it as similar to an actual virus. Particulate vaccines have been developed for a handful of pathogens, including hepatitis B and human papillomavirus, and a particulate vaccine for SARS-CoV-2 has been approved for use in South Korea.

These vaccines are especially good at activating B cells, which produce antibodies specific to the vaccine antigen.

“Particulate vaccines are of great interest for many in immunology because they give you robust humoral immunity, which is antibody-based immunity, which is differentiated from the T-cell-based immunity that the mRNA vaccines seem to elicit more strongly,” Bathe says.

A potential drawback to this kind of vaccine, however, is that the proteins used for the scaffold often stimulate the body to produce antibodies targeting the scaffold. This can distract the immune system and prevent it from launching as robust a response as one would like, Bathe says.

“To neutralize the SARS-CoV-2 virus, you want to have a vaccine that generates antibodies toward the receptor binding domain portion of the virus’ spike protein,” he says. “When you display that on a protein-based particle, what happens is your immune system recognizes not only that receptor binding domain protein, but all the other proteins that are irrelevant to the immune response you’re trying to elicit.”

Another potential drawback is that if the same person receives more than one vaccine carried by the same protein scaffold, for example, SARS-CoV-2 and then influenza, their immune system would likely respond right away to the protein scaffold, having already been primed to react to it. This could weaken the immune response to the antigen carried by the second vaccine.

“If you want to apply that protein-based particle to immunize against a different virus like influenza, then your immune system can be addicted to the underlying protein scaffold that it’s already seen and developed an immune response toward,” Bathe says. “That can hypothetically diminish the quality of your antibody response for the actual antigen of interest.”

As an alternative, Bathe’s lab has been developing scaffolds made using DNA origami, a method that offers precise control over the structure of synthetic DNA and allows researchers to attach a variety of molecules, such as viral antigens, at specific locations.

In a 2020 study, Bathe and Darrell Irvine, an MIT professor of biological engineering and of materials science and engineering, showed that a DNA scaffold carrying 30 copies of an HIV antigen could generate a strong antibody response in B cells grown in the lab. This type of structure is optimal for activating B cells because it closely mimics the structure of nano-sized viruses, which display many copies of viral proteins in their surfaces.

“This approach builds off of a fundamental principle in B-cell antigen recognition, which is that if you have an arrayed display of the antigen, that promotes B-cell responses and gives better quantity and quality of antibody output,” Lingwood says.

“Immunologically silent”

In the new study, the researchers swapped in an antigen consisting of the receptor binding protein of the spike protein from the original strain of SARS-CoV-2. When they gave the vaccine to mice, they found that the mice generated high levels of antibodies to the spike protein but did not generate any to the DNA scaffold.

In contrast, a vaccine based on a scaffold protein called ferritin, coated with SARS-CoV-2 antigens, generated many antibodies against ferritin as well as SARS-CoV-2.

“The DNA nanoparticle itself is immunogenically silent,” Lingwood says. “If you use a protein-based platform, you get equally high titer antibody responses to the platform and to the antigen of interest, and that can complicate repeated usage of that platform because you’ll develop high affinity immune memory against it.”

Reducing these off-target effects could also help scientists reach the goal of developing a vaccine that would induce broadly neutralizing antibodies to any variant of SARS-CoV-2, or even to all sarbecoviruses, the subgenus of virus that includes SARS-CoV-2 as well as the viruses that cause SARS and MERS.

To that end, the researchers are now exploring whether a DNA scaffold with many different viral antigens attached could induce broadly neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and related viruses.

The research was primarily funded by the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, and the Fast Grants program.

© Credit: The Bathe Lab

Using a virus-like delivery particle made from DNA, researchers from MIT and the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard have created a vaccine that can induce a strong antibody response against SARS-CoV-2.

The vaccine, which has been tested in mice, consists of a DNA scaffold that carries many copies of a viral antigen. This type of vaccine, known as a particulate vaccine, mimics the structure of a virus. Most previous work on particulate vaccines has relied on protein scaffolds, but the proteins used in those vaccines tend to generate an unnecessary immune response that can distract the immune system from the target.

In the mouse study, the researchers found that the DNA scaffold does not induce an immune response, allowing the immune system to focus its antibody response on the target antigen.

“DNA, we found in this work, does not elicit antibodies that may distract away from the protein of interest,” says Mark Bathe, an MIT professor of biological engineering. “What you can imagine is that your B cells and immune system are being fully trained by that target antigen, and that’s what you want — for your immune system to be laser-focused on the antigen of interest.”

This approach, which strongly stimulates B cells (the cells that produce antibodies), could make it easier to develop vaccines against viruses that have been difficult to target, including HIV and influenza, as well as SARS-CoV-2, the researchers say. Unlike T cells, which are stimulated by other types of vaccines, these B cells can persist for decades, offering long-term protection.

“We’re interested in exploring whether we can teach the immune system to deliver higher levels of immunity against pathogens that resist conventional vaccine approaches, like flu, HIV, and SARS-CoV-2,” says Daniel Lingwood, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School and a principal investigator at the Ragon Institute. “This idea of decoupling the response against the target antigen from the platform itself is a potentially powerful immunological trick that one can now bring to bear to help those immunological targeting decisions move in a direction that is more focused.”

Bathe, Lingwood, and Aaron Schmidt, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School and principal investigator at the Ragon Institute, are the senior authors of the paper, which appears today in Nature Communications. The paper’s lead authors are Eike-Christian Wamhoff, a former MIT postdoc; Larance Ronsard, a Ragon Institute postdoc; Jared Feldman, a former Harvard University graduate student; Grant Knappe, an MIT graduate student; and Blake Hauser, a former Harvard graduate student.

Mimicking viruses

Particulate vaccines usually consist of a protein nanoparticle, similar in structure to a virus, that can carry many copies of a viral antigen. This high density of antigens can lead to a stronger immune response than traditional vaccines because the body sees it as similar to an actual virus. Particulate vaccines have been developed for a handful of pathogens, including hepatitis B and human papillomavirus, and a particulate vaccine for SARS-CoV-2 has been approved for use in South Korea.

These vaccines are especially good at activating B cells, which produce antibodies specific to the vaccine antigen.

“Particulate vaccines are of great interest for many in immunology because they give you robust humoral immunity, which is antibody-based immunity, which is differentiated from the T-cell-based immunity that the mRNA vaccines seem to elicit more strongly,” Bathe says.

A potential drawback to this kind of vaccine, however, is that the proteins used for the scaffold often stimulate the body to produce antibodies targeting the scaffold. This can distract the immune system and prevent it from launching as robust a response as one would like, Bathe says.

“To neutralize the SARS-CoV-2 virus, you want to have a vaccine that generates antibodies toward the receptor binding domain portion of the virus’ spike protein,” he says. “When you display that on a protein-based particle, what happens is your immune system recognizes not only that receptor binding domain protein, but all the other proteins that are irrelevant to the immune response you’re trying to elicit.”

Another potential drawback is that if the same person receives more than one vaccine carried by the same protein scaffold, for example, SARS-CoV-2 and then influenza, their immune system would likely respond right away to the protein scaffold, having already been primed to react to it. This could weaken the immune response to the antigen carried by the second vaccine.

“If you want to apply that protein-based particle to immunize against a different virus like influenza, then your immune system can be addicted to the underlying protein scaffold that it’s already seen and developed an immune response toward,” Bathe says. “That can hypothetically diminish the quality of your antibody response for the actual antigen of interest.”

As an alternative, Bathe’s lab has been developing scaffolds made using DNA origami, a method that offers precise control over the structure of synthetic DNA and allows researchers to attach a variety of molecules, such as viral antigens, at specific locations.

In a 2020 study, Bathe and Darrell Irvine, an MIT professor of biological engineering and of materials science and engineering, showed that a DNA scaffold carrying 30 copies of an HIV antigen could generate a strong antibody response in B cells grown in the lab. This type of structure is optimal for activating B cells because it closely mimics the structure of nano-sized viruses, which display many copies of viral proteins in their surfaces.

“This approach builds off of a fundamental principle in B-cell antigen recognition, which is that if you have an arrayed display of the antigen, that promotes B-cell responses and gives better quantity and quality of antibody output,” Lingwood says.

“Immunologically silent”

In the new study, the researchers swapped in an antigen consisting of the receptor binding protein of the spike protein from the original strain of SARS-CoV-2. When they gave the vaccine to mice, they found that the mice generated high levels of antibodies to the spike protein but did not generate any to the DNA scaffold.

In contrast, a vaccine based on a scaffold protein called ferritin, coated with SARS-CoV-2 antigens, generated many antibodies against ferritin as well as SARS-CoV-2.

“The DNA nanoparticle itself is immunogenically silent,” Lingwood says. “If you use a protein-based platform, you get equally high titer antibody responses to the platform and to the antigen of interest, and that can complicate repeated usage of that platform because you’ll develop high affinity immune memory against it.”

Reducing these off-target effects could also help scientists reach the goal of developing a vaccine that would induce broadly neutralizing antibodies to any variant of SARS-CoV-2, or even to all sarbecoviruses, the subgenus of virus that includes SARS-CoV-2 as well as the viruses that cause SARS and MERS.

To that end, the researchers are now exploring whether a DNA scaffold with many different viral antigens attached could induce broadly neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and related viruses.

The research was primarily funded by the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, and the Fast Grants program.

© Credit: The Bathe Lab

The state of New Jersey has been sued twice over its infant DNA program. Like the rest of the nation, New Jersey hospitals collect a blood sample from newborns to test them for 60 different health disorders. That part is normal.

But New Jersey is different. Rather than discard the samples after the testing is complete, it holds onto them. For twenty-three years. That’s unusual. And it’s a fair bet that almost 100% of New Jersey parents are unaware of this fact.

There’s a reason parents don’t know this and it has nothing to do with parents just not paying attention when this test is performed. According to the lawsuits, New Jersey healthcare professionals do what they can to portray the testing as mandatory, even though it isn’t. They also take care to keep parents uninformed, never once informing them that they are free to opt out of the testing for religious reasons.

The state, however, is fine with this. The biggest beneficiary of this program is state law enforcement, which can freely obtain these DNA samples without having to go through the trouble of obtaining a warrant. Warrants are needed to obtain DNA samples from criminal suspects, but there’s nothing stopping cops from searching the DNA database for younger relatives of the suspect whose DNA might still be in the possession of the state’s Health Department.

That’s why the state is facing multiple lawsuits, making it an anomaly in this group of 50 states we Americans call home. And that’s likely why the state’s health officials are trying to healthwash this by crafting a new narrative for this uniquely New Jersey handling of infant blood tests. Here’s Elizabeth Nolan Brown with a summary of the rebranding for Reason.

Mandatory genomic sequencing of all newborns—it sounds like something out of a dystopian sci-fi story. But it could become a reality in New Jersey, where health officials are considering adding this analysis to the state’s mandatory newborn testing regime.

Genomic sequencing can determine a person’s “entire genetic makeup,” the National Cancer Institute website explains. Using genomic sequencing, doctors can diagnose diseases and abnormalities, reveal sensitivities to environmental stimulants, and assess a person’s risk of developing conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease.

Ernest Post, chairman of the New Jersey Newborn Screening Advisory Review Committee (NSARC), discussed newborn genomic sequencing at an NSARC meeting in May. An NSARC subcommittee has been convened to explore the issue and is expected to issue recommendations later this year. It’s considering questions such as whether sequencing would be optional or mandatory, the New Jersey Monitor reported.

The state wants to take what’s already problematic and make it a privacy nightmare. But, you know, for the children. The framing encourages people to think this is about early detection and preemptive responses to expected long-term health problems.

And that’s not to stay it won’t have the stated effect. The problem is the state hasn’t been honest about its newborn DNA collection in the past and health care providers (whether ignorant of the facts or instructed to maximize consent) haven’t been exactly trustworthy either.

Now, the state wants to expand what it can do with these blood samples despite not having done anything to correct what’s wrong with the program as it exists already. This just opens up additional avenues of abuse for the government — something it shouldn’t even be considering while it’s still facing two lawsuits related to the existing DNA harvesting program.

The ACLU is obviously opposed to this expansion. The statement it gave to the New Jersey Monitor makes it clear what’s at stake, and what needs to happen before the state moves forward with gene sequencing of newborn blood samples.

If New Jersey adopts genomic sequencing, policymakers must create “a real privacy-protective infrastructure to make sure that genomic data isn’t abused,” said Dillon Reisman, an ACLU-NJ staff attorney.

“What we’re talking about is information from kids that could allow the state and other actors to use that data to monitor and surveil them and their families for the rest of their lives,” Reisman said. “If the goal is the health of children, it does not serve the health of children to have a wild west of genomic data just sitting out there for anyone to abuse.”

Maybe that will happen before this program goes into effect. But it seems unlikely. Given the history of the existing program, the most probable outcome is a handful of alterations as the result of court orders in the lawsuits that are sure to greet the rollout of this program. The state seems super-interested in getting out ahead of health problems. But it seemingly couldn’t care less about heading off the inherent privacy problems the new program would create.

Using a virus-like delivery particle made from DNA, researchers from MIT and the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard have created a vaccine that can induce a strong antibody response against SARS-CoV-2.

The vaccine, which has been tested in mice, consists of a DNA scaffold that carries many copies of a viral antigen. This type of vaccine, known as a particulate vaccine, mimics the structure of a virus. Most previous work on particulate vaccines has relied on protein scaffolds, but the proteins used in those vaccines tend to generate an unnecessary immune response that can distract the immune system from the target.

In the mouse study, the researchers found that the DNA scaffold does not induce an immune response, allowing the immune system to focus its antibody response on the target antigen.

“DNA, we found in this work, does not elicit antibodies that may distract away from the protein of interest,” says Mark Bathe, an MIT professor of biological engineering. “What you can imagine is that your B cells and immune system are being fully trained by that target antigen, and that’s what you want — for your immune system to be laser-focused on the antigen of interest.”

This approach, which strongly stimulates B cells (the cells that produce antibodies), could make it easier to develop vaccines against viruses that have been difficult to target, including HIV and influenza, as well as SARS-CoV-2, the researchers say. Unlike T cells, which are stimulated by other types of vaccines, these B cells can persist for decades, offering long-term protection.

“We’re interested in exploring whether we can teach the immune system to deliver higher levels of immunity against pathogens that resist conventional vaccine approaches, like flu, HIV, and SARS-CoV-2,” says Daniel Lingwood, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School and a principal investigator at the Ragon Institute. “This idea of decoupling the response against the target antigen from the platform itself is a potentially powerful immunological trick that one can now bring to bear to help those immunological targeting decisions move in a direction that is more focused.”

Bathe, Lingwood, and Aaron Schmidt, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School and principal investigator at the Ragon Institute, are the senior authors of the paper, which appears today in Nature Communications. The paper’s lead authors are Eike-Christian Wamhoff, a former MIT postdoc; Larance Ronsard, a Ragon Institute postdoc; Jared Feldman, a former Harvard University graduate student; Grant Knappe, an MIT graduate student; and Blake Hauser, a former Harvard graduate student.

Mimicking viruses

Particulate vaccines usually consist of a protein nanoparticle, similar in structure to a virus, that can carry many copies of a viral antigen. This high density of antigens can lead to a stronger immune response than traditional vaccines because the body sees it as similar to an actual virus. Particulate vaccines have been developed for a handful of pathogens, including hepatitis B and human papillomavirus, and a particulate vaccine for SARS-CoV-2 has been approved for use in South Korea.

These vaccines are especially good at activating B cells, which produce antibodies specific to the vaccine antigen.

“Particulate vaccines are of great interest for many in immunology because they give you robust humoral immunity, which is antibody-based immunity, which is differentiated from the T-cell-based immunity that the mRNA vaccines seem to elicit more strongly,” Bathe says.

A potential drawback to this kind of vaccine, however, is that the proteins used for the scaffold often stimulate the body to produce antibodies targeting the scaffold. This can distract the immune system and prevent it from launching as robust a response as one would like, Bathe says.

“To neutralize the SARS-CoV-2 virus, you want to have a vaccine that generates antibodies toward the receptor binding domain portion of the virus’ spike protein,” he says. “When you display that on a protein-based particle, what happens is your immune system recognizes not only that receptor binding domain protein, but all the other proteins that are irrelevant to the immune response you’re trying to elicit.”

Another potential drawback is that if the same person receives more than one vaccine carried by the same protein scaffold, for example, SARS-CoV-2 and then influenza, their immune system would likely respond right away to the protein scaffold, having already been primed to react to it. This could weaken the immune response to the antigen carried by the second vaccine.

“If you want to apply that protein-based particle to immunize against a different virus like influenza, then your immune system can be addicted to the underlying protein scaffold that it’s already seen and developed an immune response toward,” Bathe says. “That can hypothetically diminish the quality of your antibody response for the actual antigen of interest.”

As an alternative, Bathe’s lab has been developing scaffolds made using DNA origami, a method that offers precise control over the structure of synthetic DNA and allows researchers to attach a variety of molecules, such as viral antigens, at specific locations.

In a 2020 study, Bathe and Darrell Irvine, an MIT professor of biological engineering and of materials science and engineering, showed that a DNA scaffold carrying 30 copies of an HIV antigen could generate a strong antibody response in B cells grown in the lab. This type of structure is optimal for activating B cells because it closely mimics the structure of nano-sized viruses, which display many copies of viral proteins in their surfaces.

“This approach builds off of a fundamental principle in B-cell antigen recognition, which is that if you have an arrayed display of the antigen, that promotes B-cell responses and gives better quantity and quality of antibody output,” Lingwood says.

“Immunologically silent”

In the new study, the researchers swapped in an antigen consisting of the receptor binding protein of the spike protein from the original strain of SARS-CoV-2. When they gave the vaccine to mice, they found that the mice generated high levels of antibodies to the spike protein but did not generate any to the DNA scaffold.

In contrast, a vaccine based on a scaffold protein called ferritin, coated with SARS-CoV-2 antigens, generated many antibodies against ferritin as well as SARS-CoV-2.

“The DNA nanoparticle itself is immunogenically silent,” Lingwood says. “If you use a protein-based platform, you get equally high titer antibody responses to the platform and to the antigen of interest, and that can complicate repeated usage of that platform because you’ll develop high affinity immune memory against it.”

Reducing these off-target effects could also help scientists reach the goal of developing a vaccine that would induce broadly neutralizing antibodies to any variant of SARS-CoV-2, or even to all sarbecoviruses, the subgenus of virus that includes SARS-CoV-2 as well as the viruses that cause SARS and MERS.

To that end, the researchers are now exploring whether a DNA scaffold with many different viral antigens attached could induce broadly neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and related viruses.

The research was primarily funded by the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, and the Fast Grants program.

© Credit: The Bathe Lab

Tumors constantly shed DNA from dying cells, which briefly circulates in the patient’s bloodstream before it is quickly broken down. Many companies have created blood tests that can pick out this tumor DNA, potentially helping doctors diagnose or monitor cancer or choose a treatment.

The amount of tumor DNA circulating at any given time, however, is extremely small, so it has been challenging to develop tests sensitive enough to pick up that tiny signal. A team of researchers from MIT and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard has now come up with a way to significantly boost that signal, by temporarily slowing the clearance of tumor DNA circulating in the bloodstream.

The researchers developed two different types of injectable molecules that they call “priming agents,” which can transiently interfere with the body’s ability to remove circulating tumor DNA from the bloodstream. In a study of mice, they showed that these agents could boost DNA levels enough that the percentage of detectable early-stage lung metastases leapt from less than 10 percent to above 75 percent.

This approach could enable not only earlier diagnosis of cancer, but also more sensitive detection of tumor mutations that could be used to guide treatment. It could also help improve detection of cancer recurrence.

“You can give one of these agents an hour before the blood draw, and it makes things visible that previously wouldn’t have been. The implication is that we should be able to give everybody who’s doing liquid biopsies, for any purpose, more molecules to work with,” says Sangeeta Bhatia, the John and Dorothy Wilson Professor of Health Sciences and Technology and of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at MIT, and a member of MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research and the Institute for Medical Engineering and Science.

Bhatia is one of the senior authors of the new study, along with J. Christopher Love, the Raymond A. and Helen E. St. Laurent Professor of Chemical Engineering at MIT and a member of the Koch Institute and the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard and Viktor Adalsteinsson, director of the Gerstner Center for Cancer Diagnostics at the Broad Institute.

Carmen Martin-Alonso PhD ’23, MIT and Broad Institute postdoc Shervin Tabrizi, and Broad Institute scientist Kan Xiong are the lead authors of the paper, which appears today in Science.

Better biopsies

Liquid biopsies, which enable detection of small quantities of DNA in blood samples, are now used in many cancer patients to identify mutations that could help guide treatment. With greater sensitivity, however, these tests could become useful for far more patients. Most efforts to improve the sensitivity of liquid biopsies have focused on developing new sequencing technologies to use after the blood is drawn.

While brainstorming ways to make liquid biopsies more informative, Bhatia, Love, Adalsteinsson, and their trainees came up with the idea of trying to increase the amount of DNA in a patient’s bloodstream before the sample is taken.

“A tumor is always creating new cell-free DNA, and that’s the signal that we’re attempting to detect in the blood draw. Existing liquid biopsy technologies, however, are limited by the amount of material you collect in the tube of blood,” Love says. “Where this work intercedes is thinking about how to inject something beforehand that would help boost or enhance the amount of signal that is available to collect in the same small sample.”

The body uses two primary strategies to remove circulating DNA from the bloodstream. Enzymes called DNases circulate in the blood and break down DNA that they encounter, while immune cells known as macrophages take up cell-free DNA as blood is filtered through the liver.

The researchers decided to target each of these processes separately. To prevent DNases from breaking down DNA, they designed a monoclonal antibody that binds to circulating DNA and protects it from the enzymes.

“Antibodies are well-established biopharmaceutical modalities, and they’re safe in a number of different disease contexts, including cancer and autoimmune treatments,” Love says. “The idea was, could we use this kind of antibody to help shield the DNA temporarily from degradation by the nucleases that are in circulation? And by doing so, we shift the balance to where the tumor is generating DNA slightly faster than is being degraded, increasing the concentration in a blood draw.”

The other priming agent they developed is a nanoparticle designed to block macrophages from taking up cell-free DNA. These cells have a well-known tendency to eat up synthetic nanoparticles.

“DNA is a biological nanoparticle, and it made sense that immune cells in the liver were probably taking this up just like they do synthetic nanoparticles. And if that were the case, which it turned out to be, then we could use a safe dummy nanoparticle to distract those immune cells and leave the circulating DNA alone so that it could be at a higher concentration,” Bhatia says.

Earlier tumor detection

The researchers tested their priming agents in mice that received transplants of cancer cells that tend to form tumors in the lungs. Two weeks after the cells were transplanted, the researchers showed that these priming agents could boost the amount of circulating tumor DNA recovered in a blood sample by up to 60-fold.

Once the blood sample is taken, it can be run through the same kinds of sequencing tests now used on liquid biopsy samples. These tests can pick out tumor DNA, including specific sequences used to determine the type of tumor and potentially what kinds of treatments would work best.

Early detection of cancer is another promising application for these priming agents. The researchers found that when mice were given the nanoparticle priming agent before blood was drawn, it allowed them to detect circulating tumor DNA in blood of 75 percent of the mice with low cancer burden, while none were detectable without this boost.

“One of the greatest hurdles for cancer liquid biopsy testing has been the scarcity of circulating tumor DNA in a blood sample,” Adalsteinsson says. “It’s thus been encouraging to see the magnitude of the effect we’ve been able to achieve so far and to envision what impact this could have for patients.”

After either of the priming agents are injected, it takes an hour or two for the DNA levels to increase in the bloodstream, and then they return to normal within about 24 hours.

“The ability to get peak activity of these agents within a couple of hours, followed by their rapid clearance, means that someone could go into a doctor’s office, receive an agent like this, and then give their blood for the test itself, all within one visit,” Love says. “This feature bodes well for the potential to translate this concept into clinical use.”

The researchers have launched a company called Amplifyer Bio that plans to further develop the technology, in hopes of advancing to clinical trials.

“A tube of blood is a much more accessible diagnostic than colonoscopy screening or even mammography,” Bhatia says. “Ultimately, if these tools really are predictive, then we should be able to get many more patients into the system who could benefit from cancer interception or better therapy.”

The research was funded by the Koch Institute Support (core) Grant from the National Cancer Institute, the Marble Center for Cancer Nanomedicine, the Gerstner Family Foundation, the Ludwig Center at MIT, the Koch Institute Frontier Research Program via the Casey and Family Foundation, and the Bridge Project, a partnership between the Koch Institute and the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center.

© Image: MIT News; iStock

Using a virus-like delivery particle made from DNA, researchers from MIT and the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard have created a vaccine that can induce a strong antibody response against SARS-CoV-2.

The vaccine, which has been tested in mice, consists of a DNA scaffold that carries many copies of a viral antigen. This type of vaccine, known as a particulate vaccine, mimics the structure of a virus. Most previous work on particulate vaccines has relied on protein scaffolds, but the proteins used in those vaccines tend to generate an unnecessary immune response that can distract the immune system from the target.

In the mouse study, the researchers found that the DNA scaffold does not induce an immune response, allowing the immune system to focus its antibody response on the target antigen.

“DNA, we found in this work, does not elicit antibodies that may distract away from the protein of interest,” says Mark Bathe, an MIT professor of biological engineering. “What you can imagine is that your B cells and immune system are being fully trained by that target antigen, and that’s what you want — for your immune system to be laser-focused on the antigen of interest.”

This approach, which strongly stimulates B cells (the cells that produce antibodies), could make it easier to develop vaccines against viruses that have been difficult to target, including HIV and influenza, as well as SARS-CoV-2, the researchers say. Unlike T cells, which are stimulated by other types of vaccines, these B cells can persist for decades, offering long-term protection.

“We’re interested in exploring whether we can teach the immune system to deliver higher levels of immunity against pathogens that resist conventional vaccine approaches, like flu, HIV, and SARS-CoV-2,” says Daniel Lingwood, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School and a principal investigator at the Ragon Institute. “This idea of decoupling the response against the target antigen from the platform itself is a potentially powerful immunological trick that one can now bring to bear to help those immunological targeting decisions move in a direction that is more focused.”

Bathe, Lingwood, and Aaron Schmidt, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School and principal investigator at the Ragon Institute, are the senior authors of the paper, which appears today in Nature Communications. The paper’s lead authors are Eike-Christian Wamhoff, a former MIT postdoc; Larance Ronsard, a Ragon Institute postdoc; Jared Feldman, a former Harvard University graduate student; Grant Knappe, an MIT graduate student; and Blake Hauser, a former Harvard graduate student.

Mimicking viruses

Particulate vaccines usually consist of a protein nanoparticle, similar in structure to a virus, that can carry many copies of a viral antigen. This high density of antigens can lead to a stronger immune response than traditional vaccines because the body sees it as similar to an actual virus. Particulate vaccines have been developed for a handful of pathogens, including hepatitis B and human papillomavirus, and a particulate vaccine for SARS-CoV-2 has been approved for use in South Korea.

These vaccines are especially good at activating B cells, which produce antibodies specific to the vaccine antigen.

“Particulate vaccines are of great interest for many in immunology because they give you robust humoral immunity, which is antibody-based immunity, which is differentiated from the T-cell-based immunity that the mRNA vaccines seem to elicit more strongly,” Bathe says.

A potential drawback to this kind of vaccine, however, is that the proteins used for the scaffold often stimulate the body to produce antibodies targeting the scaffold. This can distract the immune system and prevent it from launching as robust a response as one would like, Bathe says.

“To neutralize the SARS-CoV-2 virus, you want to have a vaccine that generates antibodies toward the receptor binding domain portion of the virus’ spike protein,” he says. “When you display that on a protein-based particle, what happens is your immune system recognizes not only that receptor binding domain protein, but all the other proteins that are irrelevant to the immune response you’re trying to elicit.”

Another potential drawback is that if the same person receives more than one vaccine carried by the same protein scaffold, for example, SARS-CoV-2 and then influenza, their immune system would likely respond right away to the protein scaffold, having already been primed to react to it. This could weaken the immune response to the antigen carried by the second vaccine.

“If you want to apply that protein-based particle to immunize against a different virus like influenza, then your immune system can be addicted to the underlying protein scaffold that it’s already seen and developed an immune response toward,” Bathe says. “That can hypothetically diminish the quality of your antibody response for the actual antigen of interest.”

As an alternative, Bathe’s lab has been developing scaffolds made using DNA origami, a method that offers precise control over the structure of synthetic DNA and allows researchers to attach a variety of molecules, such as viral antigens, at specific locations.

In a 2020 study, Bathe and Darrell Irvine, an MIT professor of biological engineering and of materials science and engineering, showed that a DNA scaffold carrying 30 copies of an HIV antigen could generate a strong antibody response in B cells grown in the lab. This type of structure is optimal for activating B cells because it closely mimics the structure of nano-sized viruses, which display many copies of viral proteins in their surfaces.

“This approach builds off of a fundamental principle in B-cell antigen recognition, which is that if you have an arrayed display of the antigen, that promotes B-cell responses and gives better quantity and quality of antibody output,” Lingwood says.

“Immunologically silent”

In the new study, the researchers swapped in an antigen consisting of the receptor binding protein of the spike protein from the original strain of SARS-CoV-2. When they gave the vaccine to mice, they found that the mice generated high levels of antibodies to the spike protein but did not generate any to the DNA scaffold.

In contrast, a vaccine based on a scaffold protein called ferritin, coated with SARS-CoV-2 antigens, generated many antibodies against ferritin as well as SARS-CoV-2.

“The DNA nanoparticle itself is immunogenically silent,” Lingwood says. “If you use a protein-based platform, you get equally high titer antibody responses to the platform and to the antigen of interest, and that can complicate repeated usage of that platform because you’ll develop high affinity immune memory against it.”

Reducing these off-target effects could also help scientists reach the goal of developing a vaccine that would induce broadly neutralizing antibodies to any variant of SARS-CoV-2, or even to all sarbecoviruses, the subgenus of virus that includes SARS-CoV-2 as well as the viruses that cause SARS and MERS.

To that end, the researchers are now exploring whether a DNA scaffold with many different viral antigens attached could induce broadly neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and related viruses.

The research was primarily funded by the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, and the Fast Grants program.

© Credit: The Bathe Lab

Tumors constantly shed DNA from dying cells, which briefly circulates in the patient’s bloodstream before it is quickly broken down. Many companies have created blood tests that can pick out this tumor DNA, potentially helping doctors diagnose or monitor cancer or choose a treatment.

The amount of tumor DNA circulating at any given time, however, is extremely small, so it has been challenging to develop tests sensitive enough to pick up that tiny signal. A team of researchers from MIT and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard has now come up with a way to significantly boost that signal, by temporarily slowing the clearance of tumor DNA circulating in the bloodstream.

The researchers developed two different types of injectable molecules that they call “priming agents,” which can transiently interfere with the body’s ability to remove circulating tumor DNA from the bloodstream. In a study of mice, they showed that these agents could boost DNA levels enough that the percentage of detectable early-stage lung metastases leapt from less than 10 percent to above 75 percent.

This approach could enable not only earlier diagnosis of cancer, but also more sensitive detection of tumor mutations that could be used to guide treatment. It could also help improve detection of cancer recurrence.

“You can give one of these agents an hour before the blood draw, and it makes things visible that previously wouldn’t have been. The implication is that we should be able to give everybody who’s doing liquid biopsies, for any purpose, more molecules to work with,” says Sangeeta Bhatia, the John and Dorothy Wilson Professor of Health Sciences and Technology and of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at MIT, and a member of MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research and the Institute for Medical Engineering and Science.

Bhatia is one of the senior authors of the new study, along with J. Christopher Love, the Raymond A. and Helen E. St. Laurent Professor of Chemical Engineering at MIT and a member of the Koch Institute and the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard and Viktor Adalsteinsson, director of the Gerstner Center for Cancer Diagnostics at the Broad Institute.

Carmen Martin-Alonso PhD ’23, MIT and Broad Institute postdoc Shervin Tabrizi, and Broad Institute scientist Kan Xiong are the lead authors of the paper, which appears today in Science.

Better biopsies

Liquid biopsies, which enable detection of small quantities of DNA in blood samples, are now used in many cancer patients to identify mutations that could help guide treatment. With greater sensitivity, however, these tests could become useful for far more patients. Most efforts to improve the sensitivity of liquid biopsies have focused on developing new sequencing technologies to use after the blood is drawn.

While brainstorming ways to make liquid biopsies more informative, Bhatia, Love, Adalsteinsson, and their trainees came up with the idea of trying to increase the amount of DNA in a patient’s bloodstream before the sample is taken.

“A tumor is always creating new cell-free DNA, and that’s the signal that we’re attempting to detect in the blood draw. Existing liquid biopsy technologies, however, are limited by the amount of material you collect in the tube of blood,” Love says. “Where this work intercedes is thinking about how to inject something beforehand that would help boost or enhance the amount of signal that is available to collect in the same small sample.”

The body uses two primary strategies to remove circulating DNA from the bloodstream. Enzymes called DNases circulate in the blood and break down DNA that they encounter, while immune cells known as macrophages take up cell-free DNA as blood is filtered through the liver.

The researchers decided to target each of these processes separately. To prevent DNases from breaking down DNA, they designed a monoclonal antibody that binds to circulating DNA and protects it from the enzymes.

“Antibodies are well-established biopharmaceutical modalities, and they’re safe in a number of different disease contexts, including cancer and autoimmune treatments,” Love says. “The idea was, could we use this kind of antibody to help shield the DNA temporarily from degradation by the nucleases that are in circulation? And by doing so, we shift the balance to where the tumor is generating DNA slightly faster than is being degraded, increasing the concentration in a blood draw.”

The other priming agent they developed is a nanoparticle designed to block macrophages from taking up cell-free DNA. These cells have a well-known tendency to eat up synthetic nanoparticles.

“DNA is a biological nanoparticle, and it made sense that immune cells in the liver were probably taking this up just like they do synthetic nanoparticles. And if that were the case, which it turned out to be, then we could use a safe dummy nanoparticle to distract those immune cells and leave the circulating DNA alone so that it could be at a higher concentration,” Bhatia says.

Earlier tumor detection

The researchers tested their priming agents in mice that received transplants of cancer cells that tend to form tumors in the lungs. Two weeks after the cells were transplanted, the researchers showed that these priming agents could boost the amount of circulating tumor DNA recovered in a blood sample by up to 60-fold.

Once the blood sample is taken, it can be run through the same kinds of sequencing tests now used on liquid biopsy samples. These tests can pick out tumor DNA, including specific sequences used to determine the type of tumor and potentially what kinds of treatments would work best.

Early detection of cancer is another promising application for these priming agents. The researchers found that when mice were given the nanoparticle priming agent before blood was drawn, it allowed them to detect circulating tumor DNA in blood of 75 percent of the mice with low cancer burden, while none were detectable without this boost.

“One of the greatest hurdles for cancer liquid biopsy testing has been the scarcity of circulating tumor DNA in a blood sample,” Adalsteinsson says. “It’s thus been encouraging to see the magnitude of the effect we’ve been able to achieve so far and to envision what impact this could have for patients.”

After either of the priming agents are injected, it takes an hour or two for the DNA levels to increase in the bloodstream, and then they return to normal within about 24 hours.

“The ability to get peak activity of these agents within a couple of hours, followed by their rapid clearance, means that someone could go into a doctor’s office, receive an agent like this, and then give their blood for the test itself, all within one visit,” Love says. “This feature bodes well for the potential to translate this concept into clinical use.”

The researchers have launched a company called Amplifyer Bio that plans to further develop the technology, in hopes of advancing to clinical trials.

“A tube of blood is a much more accessible diagnostic than colonoscopy screening or even mammography,” Bhatia says. “Ultimately, if these tools really are predictive, then we should be able to get many more patients into the system who could benefit from cancer interception or better therapy.”

The research was funded by the Koch Institute Support (core) Grant from the National Cancer Institute, the Marble Center for Cancer Nanomedicine, the Gerstner Family Foundation, the Ludwig Center at MIT, the Koch Institute Frontier Research Program via the Casey and Family Foundation, and the Bridge Project, a partnership between the Koch Institute and the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center.

© Image: MIT News; iStock

Using a virus-like delivery particle made from DNA, researchers from MIT and the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard have created a vaccine that can induce a strong antibody response against SARS-CoV-2.

The vaccine, which has been tested in mice, consists of a DNA scaffold that carries many copies of a viral antigen. This type of vaccine, known as a particulate vaccine, mimics the structure of a virus. Most previous work on particulate vaccines has relied on protein scaffolds, but the proteins used in those vaccines tend to generate an unnecessary immune response that can distract the immune system from the target.

In the mouse study, the researchers found that the DNA scaffold does not induce an immune response, allowing the immune system to focus its antibody response on the target antigen.

“DNA, we found in this work, does not elicit antibodies that may distract away from the protein of interest,” says Mark Bathe, an MIT professor of biological engineering. “What you can imagine is that your B cells and immune system are being fully trained by that target antigen, and that’s what you want — for your immune system to be laser-focused on the antigen of interest.”

This approach, which strongly stimulates B cells (the cells that produce antibodies), could make it easier to develop vaccines against viruses that have been difficult to target, including HIV and influenza, as well as SARS-CoV-2, the researchers say. Unlike T cells, which are stimulated by other types of vaccines, these B cells can persist for decades, offering long-term protection.

“We’re interested in exploring whether we can teach the immune system to deliver higher levels of immunity against pathogens that resist conventional vaccine approaches, like flu, HIV, and SARS-CoV-2,” says Daniel Lingwood, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School and a principal investigator at the Ragon Institute. “This idea of decoupling the response against the target antigen from the platform itself is a potentially powerful immunological trick that one can now bring to bear to help those immunological targeting decisions move in a direction that is more focused.”

Bathe, Lingwood, and Aaron Schmidt, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School and principal investigator at the Ragon Institute, are the senior authors of the paper, which appears today in Nature Communications. The paper’s lead authors are Eike-Christian Wamhoff, a former MIT postdoc; Larance Ronsard, a Ragon Institute postdoc; Jared Feldman, a former Harvard University graduate student; Grant Knappe, an MIT graduate student; and Blake Hauser, a former Harvard graduate student.

Mimicking viruses

Particulate vaccines usually consist of a protein nanoparticle, similar in structure to a virus, that can carry many copies of a viral antigen. This high density of antigens can lead to a stronger immune response than traditional vaccines because the body sees it as similar to an actual virus. Particulate vaccines have been developed for a handful of pathogens, including hepatitis B and human papillomavirus, and a particulate vaccine for SARS-CoV-2 has been approved for use in South Korea.

These vaccines are especially good at activating B cells, which produce antibodies specific to the vaccine antigen.

“Particulate vaccines are of great interest for many in immunology because they give you robust humoral immunity, which is antibody-based immunity, which is differentiated from the T-cell-based immunity that the mRNA vaccines seem to elicit more strongly,” Bathe says.

A potential drawback to this kind of vaccine, however, is that the proteins used for the scaffold often stimulate the body to produce antibodies targeting the scaffold. This can distract the immune system and prevent it from launching as robust a response as one would like, Bathe says.

“To neutralize the SARS-CoV-2 virus, you want to have a vaccine that generates antibodies toward the receptor binding domain portion of the virus’ spike protein,” he says. “When you display that on a protein-based particle, what happens is your immune system recognizes not only that receptor binding domain protein, but all the other proteins that are irrelevant to the immune response you’re trying to elicit.”

Another potential drawback is that if the same person receives more than one vaccine carried by the same protein scaffold, for example, SARS-CoV-2 and then influenza, their immune system would likely respond right away to the protein scaffold, having already been primed to react to it. This could weaken the immune response to the antigen carried by the second vaccine.

“If you want to apply that protein-based particle to immunize against a different virus like influenza, then your immune system can be addicted to the underlying protein scaffold that it’s already seen and developed an immune response toward,” Bathe says. “That can hypothetically diminish the quality of your antibody response for the actual antigen of interest.”

As an alternative, Bathe’s lab has been developing scaffolds made using DNA origami, a method that offers precise control over the structure of synthetic DNA and allows researchers to attach a variety of molecules, such as viral antigens, at specific locations.

In a 2020 study, Bathe and Darrell Irvine, an MIT professor of biological engineering and of materials science and engineering, showed that a DNA scaffold carrying 30 copies of an HIV antigen could generate a strong antibody response in B cells grown in the lab. This type of structure is optimal for activating B cells because it closely mimics the structure of nano-sized viruses, which display many copies of viral proteins in their surfaces.

“This approach builds off of a fundamental principle in B-cell antigen recognition, which is that if you have an arrayed display of the antigen, that promotes B-cell responses and gives better quantity and quality of antibody output,” Lingwood says.

“Immunologically silent”

In the new study, the researchers swapped in an antigen consisting of the receptor binding protein of the spike protein from the original strain of SARS-CoV-2. When they gave the vaccine to mice, they found that the mice generated high levels of antibodies to the spike protein but did not generate any to the DNA scaffold.

In contrast, a vaccine based on a scaffold protein called ferritin, coated with SARS-CoV-2 antigens, generated many antibodies against ferritin as well as SARS-CoV-2.

“The DNA nanoparticle itself is immunogenically silent,” Lingwood says. “If you use a protein-based platform, you get equally high titer antibody responses to the platform and to the antigen of interest, and that can complicate repeated usage of that platform because you’ll develop high affinity immune memory against it.”

Reducing these off-target effects could also help scientists reach the goal of developing a vaccine that would induce broadly neutralizing antibodies to any variant of SARS-CoV-2, or even to all sarbecoviruses, the subgenus of virus that includes SARS-CoV-2 as well as the viruses that cause SARS and MERS.

To that end, the researchers are now exploring whether a DNA scaffold with many different viral antigens attached could induce broadly neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and related viruses.

The research was primarily funded by the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, and the Fast Grants program.

© Credit: The Bathe Lab

Tumors constantly shed DNA from dying cells, which briefly circulates in the patient’s bloodstream before it is quickly broken down. Many companies have created blood tests that can pick out this tumor DNA, potentially helping doctors diagnose or monitor cancer or choose a treatment.

The amount of tumor DNA circulating at any given time, however, is extremely small, so it has been challenging to develop tests sensitive enough to pick up that tiny signal. A team of researchers from MIT and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard has now come up with a way to significantly boost that signal, by temporarily slowing the clearance of tumor DNA circulating in the bloodstream.

The researchers developed two different types of injectable molecules that they call “priming agents,” which can transiently interfere with the body’s ability to remove circulating tumor DNA from the bloodstream. In a study of mice, they showed that these agents could boost DNA levels enough that the percentage of detectable early-stage lung metastases leapt from less than 10 percent to above 75 percent.

This approach could enable not only earlier diagnosis of cancer, but also more sensitive detection of tumor mutations that could be used to guide treatment. It could also help improve detection of cancer recurrence.

“You can give one of these agents an hour before the blood draw, and it makes things visible that previously wouldn’t have been. The implication is that we should be able to give everybody who’s doing liquid biopsies, for any purpose, more molecules to work with,” says Sangeeta Bhatia, the John and Dorothy Wilson Professor of Health Sciences and Technology and of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at MIT, and a member of MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research and the Institute for Medical Engineering and Science.

Bhatia is one of the senior authors of the new study, along with J. Christopher Love, the Raymond A. and Helen E. St. Laurent Professor of Chemical Engineering at MIT and a member of the Koch Institute and the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard and Viktor Adalsteinsson, director of the Gerstner Center for Cancer Diagnostics at the Broad Institute.

Carmen Martin-Alonso PhD ’23, MIT and Broad Institute postdoc Shervin Tabrizi, and Broad Institute scientist Kan Xiong are the lead authors of the paper, which appears today in Science.

Better biopsies

Liquid biopsies, which enable detection of small quantities of DNA in blood samples, are now used in many cancer patients to identify mutations that could help guide treatment. With greater sensitivity, however, these tests could become useful for far more patients. Most efforts to improve the sensitivity of liquid biopsies have focused on developing new sequencing technologies to use after the blood is drawn.

While brainstorming ways to make liquid biopsies more informative, Bhatia, Love, Adalsteinsson, and their trainees came up with the idea of trying to increase the amount of DNA in a patient’s bloodstream before the sample is taken.

“A tumor is always creating new cell-free DNA, and that’s the signal that we’re attempting to detect in the blood draw. Existing liquid biopsy technologies, however, are limited by the amount of material you collect in the tube of blood,” Love says. “Where this work intercedes is thinking about how to inject something beforehand that would help boost or enhance the amount of signal that is available to collect in the same small sample.”

The body uses two primary strategies to remove circulating DNA from the bloodstream. Enzymes called DNases circulate in the blood and break down DNA that they encounter, while immune cells known as macrophages take up cell-free DNA as blood is filtered through the liver.

The researchers decided to target each of these processes separately. To prevent DNases from breaking down DNA, they designed a monoclonal antibody that binds to circulating DNA and protects it from the enzymes.

“Antibodies are well-established biopharmaceutical modalities, and they’re safe in a number of different disease contexts, including cancer and autoimmune treatments,” Love says. “The idea was, could we use this kind of antibody to help shield the DNA temporarily from degradation by the nucleases that are in circulation? And by doing so, we shift the balance to where the tumor is generating DNA slightly faster than is being degraded, increasing the concentration in a blood draw.”

The other priming agent they developed is a nanoparticle designed to block macrophages from taking up cell-free DNA. These cells have a well-known tendency to eat up synthetic nanoparticles.

“DNA is a biological nanoparticle, and it made sense that immune cells in the liver were probably taking this up just like they do synthetic nanoparticles. And if that were the case, which it turned out to be, then we could use a safe dummy nanoparticle to distract those immune cells and leave the circulating DNA alone so that it could be at a higher concentration,” Bhatia says.

Earlier tumor detection

The researchers tested their priming agents in mice that received transplants of cancer cells that tend to form tumors in the lungs. Two weeks after the cells were transplanted, the researchers showed that these priming agents could boost the amount of circulating tumor DNA recovered in a blood sample by up to 60-fold.

Once the blood sample is taken, it can be run through the same kinds of sequencing tests now used on liquid biopsy samples. These tests can pick out tumor DNA, including specific sequences used to determine the type of tumor and potentially what kinds of treatments would work best.

Early detection of cancer is another promising application for these priming agents. The researchers found that when mice were given the nanoparticle priming agent before blood was drawn, it allowed them to detect circulating tumor DNA in blood of 75 percent of the mice with low cancer burden, while none were detectable without this boost.

“One of the greatest hurdles for cancer liquid biopsy testing has been the scarcity of circulating tumor DNA in a blood sample,” Adalsteinsson says. “It’s thus been encouraging to see the magnitude of the effect we’ve been able to achieve so far and to envision what impact this could have for patients.”

After either of the priming agents are injected, it takes an hour or two for the DNA levels to increase in the bloodstream, and then they return to normal within about 24 hours.

“The ability to get peak activity of these agents within a couple of hours, followed by their rapid clearance, means that someone could go into a doctor’s office, receive an agent like this, and then give their blood for the test itself, all within one visit,” Love says. “This feature bodes well for the potential to translate this concept into clinical use.”

The researchers have launched a company called Amplifyer Bio that plans to further develop the technology, in hopes of advancing to clinical trials.

“A tube of blood is a much more accessible diagnostic than colonoscopy screening or even mammography,” Bhatia says. “Ultimately, if these tools really are predictive, then we should be able to get many more patients into the system who could benefit from cancer interception or better therapy.”

The research was funded by the Koch Institute Support (core) Grant from the National Cancer Institute, the Marble Center for Cancer Nanomedicine, the Gerstner Family Foundation, the Ludwig Center at MIT, the Koch Institute Frontier Research Program via the Casey and Family Foundation, and the Bridge Project, a partnership between the Koch Institute and the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center.

© Image: MIT News; iStock

Sonic the Hedgehog 3 is still seven months away, as the third live-action movie starring the blue blur and his angsty rival Shadow will premiere on December 20. And fans are eagerly anticipating the first trailer for the upcoming movie. Though some lucky ones were able to get a first look at a private event in April,…

Using a virus-like delivery particle made from DNA, researchers from MIT and the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard have created a vaccine that can induce a strong antibody response against SARS-CoV-2.

The vaccine, which has been tested in mice, consists of a DNA scaffold that carries many copies of a viral antigen. This type of vaccine, known as a particulate vaccine, mimics the structure of a virus. Most previous work on particulate vaccines has relied on protein scaffolds, but the proteins used in those vaccines tend to generate an unnecessary immune response that can distract the immune system from the target.

In the mouse study, the researchers found that the DNA scaffold does not induce an immune response, allowing the immune system to focus its antibody response on the target antigen.

“DNA, we found in this work, does not elicit antibodies that may distract away from the protein of interest,” says Mark Bathe, an MIT professor of biological engineering. “What you can imagine is that your B cells and immune system are being fully trained by that target antigen, and that’s what you want — for your immune system to be laser-focused on the antigen of interest.”

This approach, which strongly stimulates B cells (the cells that produce antibodies), could make it easier to develop vaccines against viruses that have been difficult to target, including HIV and influenza, as well as SARS-CoV-2, the researchers say. Unlike T cells, which are stimulated by other types of vaccines, these B cells can persist for decades, offering long-term protection.

“We’re interested in exploring whether we can teach the immune system to deliver higher levels of immunity against pathogens that resist conventional vaccine approaches, like flu, HIV, and SARS-CoV-2,” says Daniel Lingwood, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School and a principal investigator at the Ragon Institute. “This idea of decoupling the response against the target antigen from the platform itself is a potentially powerful immunological trick that one can now bring to bear to help those immunological targeting decisions move in a direction that is more focused.”

Bathe, Lingwood, and Aaron Schmidt, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School and principal investigator at the Ragon Institute, are the senior authors of the paper, which appears today in Nature Communications. The paper’s lead authors are Eike-Christian Wamhoff, a former MIT postdoc; Larance Ronsard, a Ragon Institute postdoc; Jared Feldman, a former Harvard University graduate student; Grant Knappe, an MIT graduate student; and Blake Hauser, a former Harvard graduate student.

Mimicking viruses

Particulate vaccines usually consist of a protein nanoparticle, similar in structure to a virus, that can carry many copies of a viral antigen. This high density of antigens can lead to a stronger immune response than traditional vaccines because the body sees it as similar to an actual virus. Particulate vaccines have been developed for a handful of pathogens, including hepatitis B and human papillomavirus, and a particulate vaccine for SARS-CoV-2 has been approved for use in South Korea.

These vaccines are especially good at activating B cells, which produce antibodies specific to the vaccine antigen.

“Particulate vaccines are of great interest for many in immunology because they give you robust humoral immunity, which is antibody-based immunity, which is differentiated from the T-cell-based immunity that the mRNA vaccines seem to elicit more strongly,” Bathe says.

A potential drawback to this kind of vaccine, however, is that the proteins used for the scaffold often stimulate the body to produce antibodies targeting the scaffold. This can distract the immune system and prevent it from launching as robust a response as one would like, Bathe says.

“To neutralize the SARS-CoV-2 virus, you want to have a vaccine that generates antibodies toward the receptor binding domain portion of the virus’ spike protein,” he says. “When you display that on a protein-based particle, what happens is your immune system recognizes not only that receptor binding domain protein, but all the other proteins that are irrelevant to the immune response you’re trying to elicit.”

Another potential drawback is that if the same person receives more than one vaccine carried by the same protein scaffold, for example, SARS-CoV-2 and then influenza, their immune system would likely respond right away to the protein scaffold, having already been primed to react to it. This could weaken the immune response to the antigen carried by the second vaccine.

“If you want to apply that protein-based particle to immunize against a different virus like influenza, then your immune system can be addicted to the underlying protein scaffold that it’s already seen and developed an immune response toward,” Bathe says. “That can hypothetically diminish the quality of your antibody response for the actual antigen of interest.”

As an alternative, Bathe’s lab has been developing scaffolds made using DNA origami, a method that offers precise control over the structure of synthetic DNA and allows researchers to attach a variety of molecules, such as viral antigens, at specific locations.

In a 2020 study, Bathe and Darrell Irvine, an MIT professor of biological engineering and of materials science and engineering, showed that a DNA scaffold carrying 30 copies of an HIV antigen could generate a strong antibody response in B cells grown in the lab. This type of structure is optimal for activating B cells because it closely mimics the structure of nano-sized viruses, which display many copies of viral proteins in their surfaces.

“This approach builds off of a fundamental principle in B-cell antigen recognition, which is that if you have an arrayed display of the antigen, that promotes B-cell responses and gives better quantity and quality of antibody output,” Lingwood says.

“Immunologically silent”

In the new study, the researchers swapped in an antigen consisting of the receptor binding protein of the spike protein from the original strain of SARS-CoV-2. When they gave the vaccine to mice, they found that the mice generated high levels of antibodies to the spike protein but did not generate any to the DNA scaffold.

In contrast, a vaccine based on a scaffold protein called ferritin, coated with SARS-CoV-2 antigens, generated many antibodies against ferritin as well as SARS-CoV-2.

“The DNA nanoparticle itself is immunogenically silent,” Lingwood says. “If you use a protein-based platform, you get equally high titer antibody responses to the platform and to the antigen of interest, and that can complicate repeated usage of that platform because you’ll develop high affinity immune memory against it.”

Reducing these off-target effects could also help scientists reach the goal of developing a vaccine that would induce broadly neutralizing antibodies to any variant of SARS-CoV-2, or even to all sarbecoviruses, the subgenus of virus that includes SARS-CoV-2 as well as the viruses that cause SARS and MERS.

To that end, the researchers are now exploring whether a DNA scaffold with many different viral antigens attached could induce broadly neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and related viruses.

The research was primarily funded by the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, and the Fast Grants program.

© Credit: The Bathe Lab

Tumors constantly shed DNA from dying cells, which briefly circulates in the patient’s bloodstream before it is quickly broken down. Many companies have created blood tests that can pick out this tumor DNA, potentially helping doctors diagnose or monitor cancer or choose a treatment.

The amount of tumor DNA circulating at any given time, however, is extremely small, so it has been challenging to develop tests sensitive enough to pick up that tiny signal. A team of researchers from MIT and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard has now come up with a way to significantly boost that signal, by temporarily slowing the clearance of tumor DNA circulating in the bloodstream.

The researchers developed two different types of injectable molecules that they call “priming agents,” which can transiently interfere with the body’s ability to remove circulating tumor DNA from the bloodstream. In a study of mice, they showed that these agents could boost DNA levels enough that the percentage of detectable early-stage lung metastases leapt from less than 10 percent to above 75 percent.

This approach could enable not only earlier diagnosis of cancer, but also more sensitive detection of tumor mutations that could be used to guide treatment. It could also help improve detection of cancer recurrence.

“You can give one of these agents an hour before the blood draw, and it makes things visible that previously wouldn’t have been. The implication is that we should be able to give everybody who’s doing liquid biopsies, for any purpose, more molecules to work with,” says Sangeeta Bhatia, the John and Dorothy Wilson Professor of Health Sciences and Technology and of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at MIT, and a member of MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research and the Institute for Medical Engineering and Science.

Bhatia is one of the senior authors of the new study, along with J. Christopher Love, the Raymond A. and Helen E. St. Laurent Professor of Chemical Engineering at MIT and a member of the Koch Institute and the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard and Viktor Adalsteinsson, director of the Gerstner Center for Cancer Diagnostics at the Broad Institute.

Carmen Martin-Alonso PhD ’23, MIT and Broad Institute postdoc Shervin Tabrizi, and Broad Institute scientist Kan Xiong are the lead authors of the paper, which appears today in Science.

Better biopsies

Liquid biopsies, which enable detection of small quantities of DNA in blood samples, are now used in many cancer patients to identify mutations that could help guide treatment. With greater sensitivity, however, these tests could become useful for far more patients. Most efforts to improve the sensitivity of liquid biopsies have focused on developing new sequencing technologies to use after the blood is drawn.

While brainstorming ways to make liquid biopsies more informative, Bhatia, Love, Adalsteinsson, and their trainees came up with the idea of trying to increase the amount of DNA in a patient’s bloodstream before the sample is taken.

“A tumor is always creating new cell-free DNA, and that’s the signal that we’re attempting to detect in the blood draw. Existing liquid biopsy technologies, however, are limited by the amount of material you collect in the tube of blood,” Love says. “Where this work intercedes is thinking about how to inject something beforehand that would help boost or enhance the amount of signal that is available to collect in the same small sample.”

The body uses two primary strategies to remove circulating DNA from the bloodstream. Enzymes called DNases circulate in the blood and break down DNA that they encounter, while immune cells known as macrophages take up cell-free DNA as blood is filtered through the liver.

The researchers decided to target each of these processes separately. To prevent DNases from breaking down DNA, they designed a monoclonal antibody that binds to circulating DNA and protects it from the enzymes.

“Antibodies are well-established biopharmaceutical modalities, and they’re safe in a number of different disease contexts, including cancer and autoimmune treatments,” Love says. “The idea was, could we use this kind of antibody to help shield the DNA temporarily from degradation by the nucleases that are in circulation? And by doing so, we shift the balance to where the tumor is generating DNA slightly faster than is being degraded, increasing the concentration in a blood draw.”

The other priming agent they developed is a nanoparticle designed to block macrophages from taking up cell-free DNA. These cells have a well-known tendency to eat up synthetic nanoparticles.

“DNA is a biological nanoparticle, and it made sense that immune cells in the liver were probably taking this up just like they do synthetic nanoparticles. And if that were the case, which it turned out to be, then we could use a safe dummy nanoparticle to distract those immune cells and leave the circulating DNA alone so that it could be at a higher concentration,” Bhatia says.

Earlier tumor detection