Mission to Israel Part VII: The Surveillance Video

[This is the seventh post in my series on my mission to Israel. You can read Parts I, II, III, IV, V, and VI.]

On the final day of our mission to Israel, we visited the headquarters of the IDF Spokesperson in Tel Aviv. This is the public affairs department of the Israeli military. We would attend a screening of surveillance footage of the October 7 attacks. This was a moment I had been thinking about since I agreed to go on the trip. Would I watch it? This descriptions in this post will be quite graphic, though I encourage you–for reasons that will be made clear at the end–to read on through.

The Holocaust and October 7 Happened

To this day, people deny the Holocaust happened. Some claim the entire Shoach is a fiction. Others claims that there was some murders, but the number of deaths was been greatly exaggerated. Others assert that the German government was not behind the mass exterminations. And so on. What is remarkable is that people hold these views in the face of mountains of evidence. The Nazis were quite proud of their efforts, and documented their systematic efforts to wipe the Jewish people off the map. If you haven't visited the Holocaust museums in Washington, D.C. or New York, you should. And if you went a long time ago, you should go again.

Still, when you visit these institutions, all of the photographs are black-and-white, and the videos are grainy. Though we know these accounts are real, watching them feels like watching a history movie. Nearly nine decades removed, they seem like a thing of the past. And Holocaust deniers insist that these sources are doctored or manufactured.

October 7, 2023, however, is still raw and fresh. And much like the Nazis before them, Hamas was proud of their barbarism. They recorded their acts of terror with body-cameras. They livestreamed murders–often on their victims' phones. They shared on social media photos and videos of horrific acts. All in high definition! There are already specters of October 7th denialism–perhaps the most egregious is that the Hamas terrorists did not commit rapes because their religion forbids it. I saw this claim repeated in the press, without any skepticism. But Hamas documented their own atrocities.

Should I Watch The Video?

In the wake of October 7, Israeli forces collected these photos and videos to document the horrors. Moreover, there were recordings by Israelis on dashboard cameras, doorbell cameras, and other surveillance systems. The Israeli government compiled these scenes into a single movie that stretches about fifty minutes. While many, if not most, of the individual clips can be found online, the compiled footage is kept under strict control. It is only exhibited at secure facilities to certain guests who are cleared.

Members of the Israeli military are not allowed to watch it. It is considered far too traumatic, and traumatizing for people who have lived through October 7. None of my family members in Israel had watched. They had no doubts about what happened on October 7, so why go through the pain of enduring the day again? My Rabbi told me not to watch it. There is a teaching to not cause any shame for dead people. He asked if the people who had been murdered in those videos would want me to watch them in such a terrible state. These were all fair points.

I thought long and hard about whether I would watch it. Initially, on a personal level, I was inclined not to. I do not like horror movies. Generally, if there is any movie with blood or gore, I turn it off. I can't even watch medical programs that depict surgery and other procedures. I close my eyes when I get a shot or have dental work. Yes, I am quite squeamish. There is an expression that is far too overused–"You can't unsee this!" But it is very apt for the surveillance video. I knew that these fifty minutes of pure, uncensored barbarism would haunt me for the rest of my life.

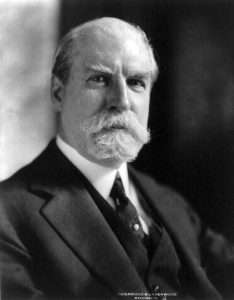

What turned me was a presentation I saw by Judge Roy Altman, who led a mission to Israel for federal judges. Altman described, in graphic detail, what he saw. He has given this lecture in many places, and it is moving. After the lecture, I asked Altman point blank if he regretted watching the videos. On one level, he did, as these images would never leave him. But on a deeper level, watching these videos made his message that much more powerful. Having witnessed the savagery, he could now spread the message around the globe. And this is not a second-hand account. He watched the video with his own eyes. And he didn't simply scan through a few clips on social media. He endured the entire curated film, with no break, in an Israeli military facility.

Altman's explanation persuaded me to watch it. I routinely lecture at law schools and other venues throughout the country. This year, I plan to talk about Israel–if any law school is brave enough to host me. (So far only a few takers.) I intend to relay the medieval acts of terror I witnessed. Having personally seen these clips will allow me to speak to the issue in a way I simply could not have by reading about it. I regret that I personally had to endure the screening. (Although whatever minor inconvenience I had pales in comparison to the suffering that happened on October 7, and to this day.) And to this day, I cannot forget what I saw. I recently watched the Deadpool-Wolverine movie. In one scene, a character decapitates another character, and holds the head up like a trophy. The audience roared in gruesome laughter. I didn't. I saw an actual video of a Hamas terrorist hacking off an innocent person's head, stretching out the skin, and dangling the head by the scalp as the lifeless body lay on the ground. But this was the choice I made, and I think it was the right one.

Not everyone on our mission watched the video. Several members of our mission excused themselves from the room before the screening began. I fully understand their decision. Everyone can bear witness to atrocities in the way that works for them. Indeed, even going to Israel was a risk, as our safety could not be fully assured at all junctures.

The Screening

We would watch the movie in a military briefing room. This was not a cushy movie theater. We were seated in what looked like any law school classroom, with some large displays at the front of the room. There was a clock, which allowed us to keep track of time. I had to leave my phone in a locker outside, as recording was prohibited.

A female officer in the Spokesperson Unit gave a brief introduction. I understand that she is one of the few people in the military who has clearance to watch the video. I can't even fathom what trauma she endures by watching this video each and every day, as different delegations come through. She explained this was the twenty-third version of the video. Apparently, the earlier iterations were even more violent. They showed torture, including the cutting of breasts, a newborn who was shot in the head, and other acts of barbarism. Moreover, there was footage of genital mutilation. Some of the families objected. The faces on those clips were either blurred out, or the clips were removed altogether out of respect for the family. Just think that some video editor within the Israeli government had the harrowing task of winnowing down these clips.

The officer only gave a few preparatory remarks. One, that stuck with me, was how she described the terrorists. She used the word "glee." These were not soldiers who were performing a mission. They were not in any way struggling with their actions. They were joyful for having the chance to kill so many innocent Israelis. It was like they were playing a first-person shooter, but in real life. And they kept repeating one refrain over and over and over again. Allahu Akhbar. Allahu Akhbar. Allahu Akhbar. In almost every scene, the men repeated that phrase at the top of their lungs.

With those brief remarks, the officer started to play the video.

Scenes from the Video

It is difficult to describe in words what I saw. During the fifty-minute video, I sat in stunned silence, with each scene worse than the one before. At a few junctures, I had to close my eyes. When I opened them, I hoped the particular scene would be over, but it wasn't. Occasionally, I would look around the room at the fellow law professors. They all had the same looked of being stunned and mortified. Some closed their eyes. Others put their heads in their hands.

Immediately after the video finished, I started to write down in a notebook everything I could recall. I knew that the particulars would evanesce from my mind, even if the general gore would remain. What follows is a scattered list of my recollections. It does not have any sort of pattern or coherent flow, as the actual surveillance video had none. And it is entirely possible that some of these recollections are composites–a few different scenes were seared together in my memory. But I remember each of these tragic events occurred.

- There were pools of blood on the ground. In movies, blood looks bright red and shiny. but in reality, it is much darker, and quickly absorbs into the dirt. It looks brownish. If I didn't know what it was, I might think it was spilled motor oil.

- Bodies were burned alive in cars. The Hamas terrorists brought accelerant with them, and placed it on the tires and the hoods of the car, so they burned hotter, faster, and longer. One charred corpse was reaching out of the car, trying to escape, but never would. The scorched bodies reminded me of footage from the Holocaust. But unlike grainy footage at a Holocaust museum, these scenes were in full HD.

- One woman was murdered. The terrorists took her phone, and livestreamed it on her social media account. The woman's family learned of her death when she "went live"–something she apparently never did–and saw it in real time.

- A father finds his daughter's burned body. He screams in agony that it is not his daughter. Another woman said that those were the daughter's tattoos. The father refused to believe it. This young woman's legs were spread apart. She was not wearing any undergarments. There was blood between her legs.

- One Hamas terrorist was wearing a Palestinian flag on his body armor. All I could think of was those college students who wave the Palestinian flag around without having any clue what that flag represents.

- There was a radio call intercepted between a Hamas terrorist who entered Israel, and his commander back in Gaza. The commander ordered him to bring a body back to Gaza, and the people could play with the body parts in the square–like a Soccer game.

- There was footage of a bar, plastered with Coca-Cola signs. Many innocent people were hiding behind the bar, but they were shot and killed. Bodies were stacked one on top of another.

- People hid in dumpsters and port-a-potties. They were covered in garbage and feces when they were shot dead.

- One Hamas terrorist dragged a bleeding body from a bedroom all the way outside. The blood streaked across the floor, the entire way.

- A terrorist was piling dead bodies in a pickup truck. The Jewish tradition is to bury all human remains. Hamas knew this, and brought the corpses back to Gaza, so not even the dead could be buried.

- There was another intercepted radio call. A commander said that a captured Israel soldier should be hanged in a square.

- Bodies of captured hostages were paraded in Gaza. The Hamas terrorists actually had to protect the hostages to prevent them from being lynched. For many of these Israelis, their last time being outside was among these mobs.

- At the Nova music festival, young women had their genitals mutilated. They were bound and their clothes were pulled off. Understandably, rape kits were not performed under the circumstances. As a result, much of the evidence of rape was buried with these poor souls.

- Surveillance footage showed a dog approaching a terrorist. The dog looked friendly, and posed no threat. The terrorist shot the dog once. The dog huddled over but kept walking. Two shots, and the dog fell over, but was still moving. Three shots, and the dog died.

- A terrorist tried to decapitate a person. But he was using a dull garden hoe, so he couldn't cut through all the way. He kept hacking and hacking and hacking at the neck, but it didn't sever all the way. The head sort of flopped over, but was still connected. This sort of medieval barbarism belongs in a different millennium.

- It is early in the morning. A father and his two sons run from their bedrooms into the living room. The boys (about 7 and 9 years old) are still wearing their underwear. They run into a bomb shelter in their backyard. These shelters are meant to protect people from explosions, but are not locked. Several terrorists throw a grenade into the shelter. It explodes. The surmise is that the father jumped on the grenade. He died.The terrorists bring both of the boys into the backyard and are yelling at them. The boys are then left alone in the living room. One boy says, "I think we are going to die." The other says, "Dad is dead." One of the boy's eye is bleeding. The brother asks if he can see out of that eye. He cannot. They are sitting there, crying, unsure of what to do. Somehow, they manage to escape and run to a cousin's house and survived. The boy would lose his eye. Later, the mother would come home and see the shelter, and her husband's corpse. The agony on her face was heart wrenching.

- Hamas terrorists enter a kindergarten. There are posters of Queen Elsa from Frozen, which is one of my daughters' favorite movies. Another corpse of a young child is shown wearing Mickey Mouse pajamas, which were stained with blood.

- Hamas terrorists were setting a house on fire after killing the occupants. They used accelerants to make the fire burn hotter. One shouted "burn it down." The symbolism was clearly intended to invoke the Holocaust. There was shattered glass everywhere, which invoked Kristallnacht.

- I've seen countless movies where a person is shot. Usually, the person who is shot stumbles, falls, and moves around a bit afterwards. The dying is very dramatic. In reality, a person shot at close range in cold blood immediately drops and dies almost instantaneously.

- One terrorist repeated over and over again "This is for history" and "We are heroes." They truly believed they were making history, and they would be remembered as heroes. But not in the way they intended.

- In another video, the decapitation was successful. After many cuts, the head was fully severed off. The skin sort of draped over the neck. It reminded me of the stretch-faced characters from Beetlejuice. And like in the Deadpool movie, the terrorist held up the head by the hair, as if it was a trophy. The lifeless body was bent on his knees. Hamas social media uploaded a photo of that headless body. During the decapitation. I kept closing my eyes, hoping the scene would be over, but it wasn't. It continued on and on.

- There was a burned head that was severed in half. The teeth were burned. It looked like a mummy from ancient Egypt.

- The IDF intercepted a voice call between a Hamas terrorist and his parents in Gaza. The son told his father, beaming with pride, that he killed 10 Jews with his bare hands. He kept telling his father to check his Whatsapp. (Someone should tell him who the founder of Meta is.) Then he says, "I want to talk to mom." As if he got a sterling report card. His mother was so proud. She said "Praise to god" and "Kill, Kill, Kill."

The Aftermath

The video concluded abruptly, without any notice. It was over. We were then given a short break. I was stunned. I walked out into the courtyard for some fresh air. A fellow law professor was crying on the ground. I gave him a hug, even though I felt about the same.

We were brought back into the classroom to discuss what we had witnessed. I didn't have many words. All I could think of was asking how the officer was able to watch this video day-in and day-out.

After the presentation, we had a briefing from some IDF military lawyers (MAG). I wrote about some of what I learned from the military lawyers here. In truth, I was pretty distracted, but I tried to pay attention as closely as I could. It amazed me that knowing how horrific these atrocities were, the military lawyers could still be so committed to these international institutions that treat Israel so unfairly.

Afterwards, we went to lunch with several of the soldiers from the Public Spokesperson division. One of them, Oriyah Solomon, was an Orthodox female who recently was married. Until recently, there was no obligation for observant Jews to serve, and certainly no expectation that "frum" women would serve. But she volunteered, in part to demonstrate that other religious women can serve their countries. I found her message inspiring.

Who Should Watch This Video?

Israel has not released this video to the general public. The fear is that if it is released, it would make a splash for a short period, and then quickly be forgotten. And, in turn, it would cheapen the atrocities. Some may actually valorize the killers, and it could be used as propaganda. Frankly, I do not think most people would have the stomach, or motivation to sit through the full hour of footage. They may watch a brief clip, and then shut it down. There was something meaningful in watching the clips at a secure facility, in a room full of interested people, with a military chaperone. I would never forget it.

The post Mission to Israel Part VII: The Surveillance Video appeared first on Reason.com.

The front page of CNN.com blares the

The front page of CNN.com blares the