What Is an Electronic Sackbut?

If you, like me, think of musical synthesizers as an artifact of 1970s rock and disco, then you, like me, will be surprised to learn that the first electronic synthesizer predates those genres by several decades

In 1945, Hugh Le Caine, a physicist at Canada’s National Research Council, began working in his spare time on a single-channel musical instrument he dubbed the Electronic Sackbut. He was intrigued by the fact that the three auditory sensations associated with music—namely, pitch, loudness, and timbre—had counterparts in electronics—namely, frequency, amplitude, and the harmonic spectrum obtained by Fourier analysis. To demonstrate those qualities, Le Caine created a synthesizer that mimicked, among other things, a brass horn known as the sackbut. It could also synthesize other horns, as well as string and reed instruments. He envisioned using the electronic sackbut in live performances, to play orchestral, big band, and experimental jazz music.

Here’s a recording of one Le Caine composition, “The Sackbut Blues”:

Short presentation of the 1948 sackbut: the sackbut blues www.youtube.com

What is a sackbut?

All of my friends who are into Renaissance music love the 2004 Coen brothers film The Ladykillers because it contains one of the few modern references to the sackbut. The original sackbut emerged in the 15th century, and it had a telescopic slide used to change pitch. It fell out of favor by the 18th century, only to be reborn as the modern-day trombone.

Le Caine chose to name his synthesizer after a thoroughly obsolete instrument to “afford the designer a certain measure of immunity from criticism.” That is, the electronic sackbut was its own invention, not an imitation of a known sound.

Hugh Le Caine demonstrates the left-hand control for timbre and the right-hand control for pitch and volume.National Research Council Canada Archives

Hugh Le Caine demonstrates the left-hand control for timbre and the right-hand control for pitch and volume.National Research Council Canada Archives

Le Caine’s first electronic sackbut [shown at top] had all of the aesthetic roughness of an experimental prototype. He built it himself with whatever was on hand, valuing functionality over appearance. He constructed the stand out of pieces of packing crates, not bothering to remove staples or bits of cloth. The boards weren’t measured and cut to fit at nice, neat right angles. The result was a haphazard contraption that looked like it could collapse at any moment. Pencil marks with the inventor’s notations and directions remain scribbled across the top.

He also winged it with the prototype’s electronics. In a 1955 letter, Le Caine admitted, “Confidentially, I have never made a complete drawing of the sackbut and have only drawn parts of it when people have asked about it.” This, of course, makes it difficult to describe the prototype’s electronics, especially considering that he kept changing them as his ideas evolved. Because it was a prototype, Le Caine would just clip wires and resolder components without always cleaning up after himself. Bill Keen, an associate of Le Caine’s at the NRC field station, described the instrument this way: “The components just hung out the side like spaghetti, and you’d just have to push them back in.”

Luckily for us, Le Caine’s biographer Gayle Young worked out much of the electronic controls and described the instrument (as well as his other musical inventions) in her 1991 book, The Sackbut Blues. The original electronic sackbut, completed in 1948, predated the invention of transistors, so it used a combination of vacuum tubes, oscillators, resistors, and the occasional device borrowed from Le Caine’s nuclear physics lab. For example, the player’s right hand controlled the volume using a pressure-sensitive keyboard mounted on springs. The movement of the springs was converted to voltage by two condensers, one at each end of the keyboard. Each key was associated with a particular note, but the pitch of the note could be tuned by rolling back and forth on the key, similar to how a violinist might produce a vibrato or glissando.

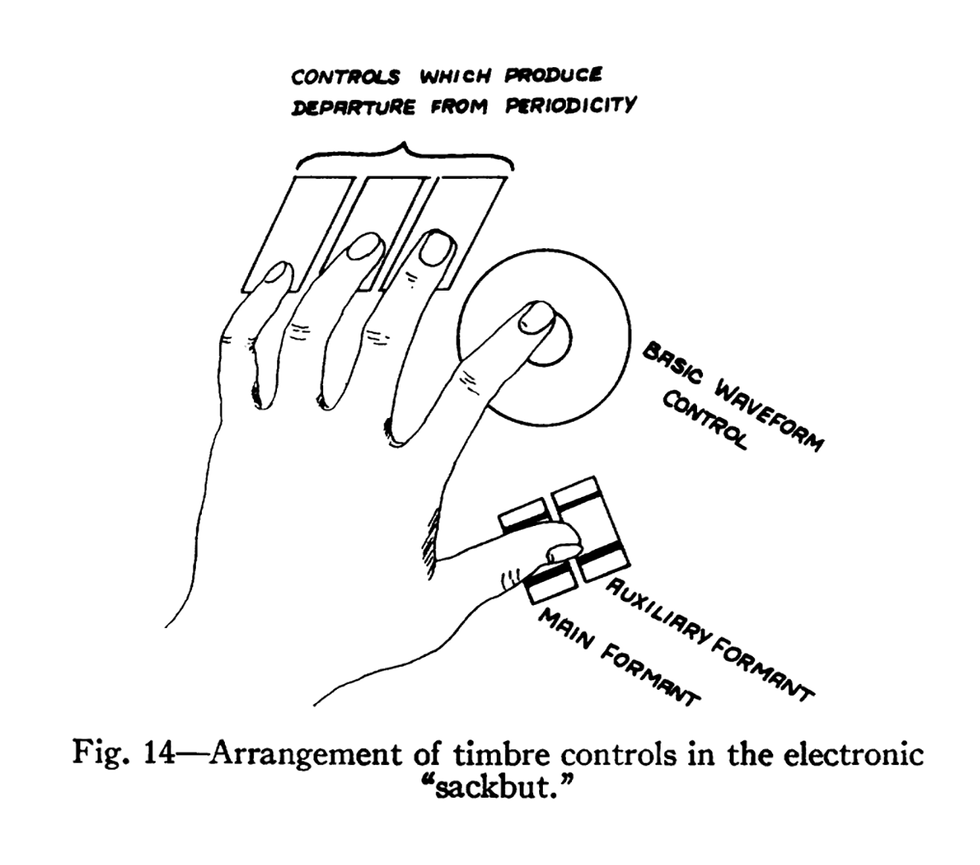

The player’s left hand was used to control the timbre of the electronic sackbut, as shown in Hugh Le Caine’s 1956 paper in Proceedings of the IRE. Proceedings of the IRE

The player’s left hand was used to control the timbre of the electronic sackbut, as shown in Hugh Le Caine’s 1956 paper in Proceedings of the IRE. Proceedings of the IRE

The player’s left hand controlled the timbre with three types of frequency modulation. The thumb controlled the formant (that is, the amplitude peak in the spectrum that distinguishes the instrument’s timbre), the index finger controlled the waveform using a circular grid, and the three remaining fingers controlled the periodicity.

Throughout his life, Le Caine pursued the idea of a “beautiful sound” —something meaningful, rich, complex, and imaginative. He wanted to overcome the popular perception of electronic instruments as sounding mechanical and uninteresting. According to Young, he wanted the electronic sackbut to be as satisfying as a violin, with the same nuance and variation, but easier to learn to play. Admittedly, I have only read about how to play the electronic sackbut, but it sounds difficult to learn to manipulate in a fashion that would produce a soothing sound.

The electronic sackbut used an assortment of repurposed electronics, which Le Caine tweaked as he experimented. Don Kennedy/National Music Centre

The electronic sackbut used an assortment of repurposed electronics, which Le Caine tweaked as he experimented. Don Kennedy/National Music Centre

Where did the electronic sackbut originate?

I always find it interesting to consider the environment in which an invention incubates. In the case of the electronic sackbut, the instrument emerged in the shadow of the National Research Council, Canada’s federal agency for R&D in science and technology, where Le Caine worked for much of his career. How did he come to invent this extraordinary musical instrument, and how did he convince the NRC to support his work?

Le Caine had graduated from Queen’s University, in Kingston, Ont., with a master’s in physical engineering in 1939 and then joined the NRC, doing classified work on radar for the army. (Canada had a robust radar program during World War II, as I touched on in this column.)

At the conclusion of the war, Le Caine hoped to turn his attention full time to electronic music, an interest he had been toying with for at least a decade. He considered joining the acoustics lab at NRC, until he realized they were only interested in measuring the properties of sound, not in the aesthetics. He also considered joining an equipment manufacturer, such as the Hammond Organ Co., but he wanted to do fundamental research rather than commercial applications. In the end, he opted to continue working for the NRC on various nonmusical projects, including the microtron, a type of particle accelerator. But he investigated electronic music in his spare time.

Le Caine’s penciled notations and directions remain scribbled across the top of the electronic sackbut.Don Kennedy/National Music Centre

Le Caine’s penciled notations and directions remain scribbled across the top of the electronic sackbut.Don Kennedy/National Music Centre

Beginning in 1945, Le Caine rented one of the hastily built wartime houses at the NRC field station southeast of Ottawa. He designated one room for all of the instruments he had accumulated, both traditional (piano, violin, guitar, drums) and experimental (homemade electronic organ and other instruments). A separate room was used for recording. And a final room, which also doubled as his bedroom, was his electronics lab, which he filled with voltmeters, oscillators, filters, and an oscilloscope.

It was in this house that Le Caine built the first electronic sackbut. By the summer of 1946, he and his friends could play it. Le Caine hosted regular jam sessions at his house, and they even made recordings of some of the compositions.

The electronic sackbut finds an audience

Day jobs have a tendency to interfere with hobbies, and based on Le Caine’s work on the microtron, he was awarded an NRC doctoral scholarship in 1948. He dismantled the electronic sackbut, put it in storage, and headed to England to study nuclear physics at the University of Birmingham.

Three years later, Ph.D. in hand, Le Caine returned to Ottawa and the NRC, and he continued working on electronic music in his spare time. Luckily, Helen Pattenson intervened. Pattenson was the section secretary in Le Caine’s unit, and she was also a member of the Scientists’ Wives’ Association. Knowing about Le Caine’s interest in electronic instruments, she invited him to give a talk to the association. Le Caine said he needed a few months to reassemble the sackbut. Pattenson then suggested to her supervisor, George Miller, that Le Caine be allowed to work on the electronic sackbut at NRC during normal business hours. Miller agreed.

From time to time, Miller stopped by Le Caine’s fledgling electronic music lab at the NRC, and he liked what he saw (and heard). Miller invited his boss, Guy Ballard, to the lab, and Ballard also became intrigued. Eventually, they got the president of the NRC, E.W.R. Steacie, to look at Le Caine’s work.

Hugh Le Caine’s first electronic sackbut had all of the aesthetic roughness of an experimental prototype.

Le Caine gave his first lecture to the Scientists’ Wives’ Association in the fall of 1953, followed in the spring by two more lectures, one for the NRC staff and one for the general public. He introduced the basics of electronic sound generation, discussed his theories about music, and demonstrated his instruments. After the third lecture, Steacie recommended that Le Caine be allowed to oversee a small project in electronic music at NRC. After almost 15 years of working for the organization, Le Caine finally had a formal lab where he could blend his interests in electronics and music.

Le Caine continued to work at NRC until his retirement in 1974. Over his lifetime, he developed more than 20 different electronic musical instruments, including the Sonde, the Polyphone, and the Special Purpose Tape Recorder. He crafted a number of components, such as voltage-controlled amplifiers, filters, and oscillators, that he reused in his instruments.

Today, many of those creations can be found in the Hugh Le Caine Collection of Midcentury Electronic Musical Instrument Design, along with related artifacts, recordings, and operation manuals. The collection began in 1975, when the Ingenium’s Museums of Science and Innovation, in Ottawa, acquired the prototype electronic sackbut. Curator Tom Everrett is leading a conservation effort to stabilize the prototype, map its electronics, and build a replica to reproduce the sounds, as this video explains:

Sackbut Conservation Project (Excerpt) www.youtube.com

Part of a continuing series looking at historical artifacts that embrace the boundless potential of technology.

An abridged version of this article appears in the February 2024 print issue as “Behold the Electronic Sackbut.”

References

I was introduced to the electronic sackbut by Tom Everrett, a curator at the Ingenium, in Ottawa, during IEEE Sections Congress in 2023.

I then turned to Hugh Le Caine’s own words, first by reading his article “Electronic Music” in the Proceedings of the IRE and then his discussion with musicians, “Synthetic Means,” at the International Conference of Composers in 1960 and subsequently published in The Modern Composer and His World.

Finally, Gayle Young’s 1991 biography of Le Caine, The Sackbut Blues, was an indispensable resource.