Why Libertarians Hate Kamala Harris' Economic Platform

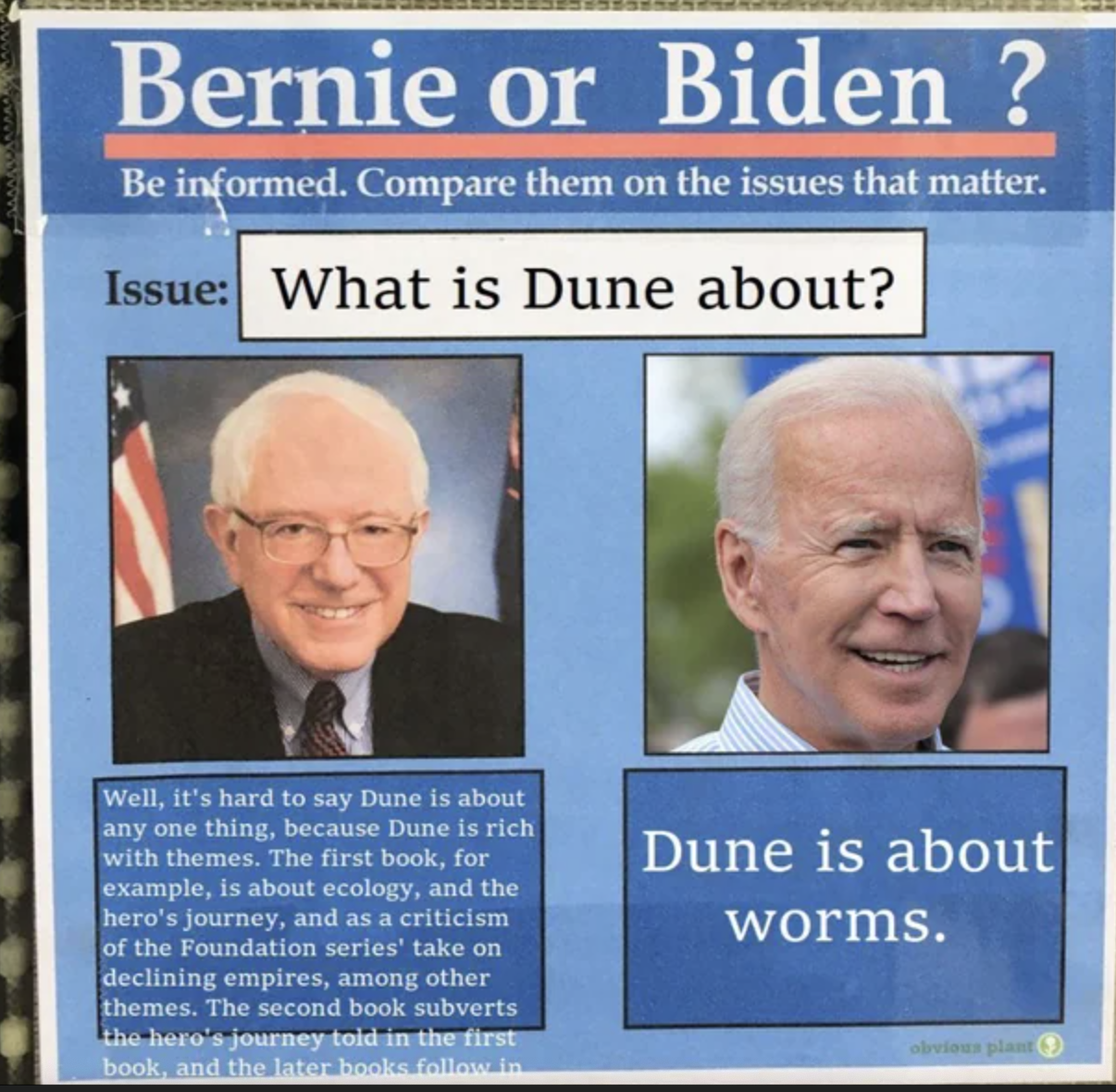

In this week's The Reason Roundtable, editors Peter Suderman, Katherine Mangu-Ward, and Nick Gillespie welcome special guest Ben Dreyfuss onto the pod ahead of this week's Democratic National Convention in Chicago to talk about Kamala Harris' truly terrible economic policy proposals.

02:48—Dreyfuss' YIMBY conversion thanks to Reason

13:20—Harris drops some lousy economic policy ideas.

32:37—The DNC begins.

44:25—Weekly Listener Question

53:33—Tariffs are timeless.

1:03:32—This week's cultural recommendations

Mentioned in this podcast:

"Kamala Harris' Dishonest and Stupid Price Control Proposal," by J.D. Tuccille

"DNC Readies for Protesters," by Liz Wolfe

"Harris' Economic Illiteracy," by Liz Wolfe

"Harris Joins the FTC's Food Fight Against Kroger-Albertsons Merger," by C. Jarrett Dieterle

"The times demand serious economic ideas. Harris supplies gimmicks." by the Washington Post editorial board

The price tag of @KamalaHarris's big, bold economic plan? According to penny pinchers at @BudgetHawks, a mere $1.7 to $2 trillion over the next decade. Given that gross debt is $35 trillion, maybe it's time to tap the brakes a bit?https://t.co/qA5wFJleLw pic.twitter.com/q80MwxoRD9

— Nick Gillespie (@nickgillespie) August 16, 2024

"When your opponent calls you 'communist,' maybe don't propose price controls?" Catherine Rampell

"How did Doug Emhoff hear Biden was out? After taking a SoulCycle class in WeHo. Without his phone," by Kevin Rector

"Database Nation: The Upside of 'Zero Privacy,'" by Declan Mccullagh

"Alien: Romulus Is a Slick, Empty Franchise Pastiche," by Peter Suderman

The Calm Down Substack by Ben Dreyfuss

https://x.com/nickgillespie/status/1824430467191312525

Upcoming Events:

- "Is the American Dream Alive?" A Free Press debate with Katherine Mangu-Ward on Tuesday, September 10 in Washington, D.C.

- "Reason Speakeasy: Kat Timpf & Nick Gillespie" on Wednesday, September 11 in New York

Send your questions to roundtable@reason.com. Be sure to include your social media handle and the correct pronunciation of your name.

Today's sponsors:

- Lumen is the world's first handheld metabolic coach. It's a device that measures your metabolism through your breath. On the app, it lets you know if you're burning fat or carbs, and it gives you tailored guidance to improve your nutrition, workouts, sleep, and even stress management. All you have to do is breathe into your Lumen first thing in the morning, and you'll know what's going on with your metabolism, whether you're burning mostly fats or carbs. Then, Lumen gives you a personalized nutrition plan for that day based on your measurements. You can also breathe into it before and after workouts and meals, so you know exactly what's going on in your body in real time, and Lumen will give you tips to keep you on top of your health game. Your metabolism is your body's engine—it's how your body turns the food you eat into fuel that keeps you going. Because your metabolism is at the center of everything your body does, optimal metabolic health translates to a bunch of benefits, including easier weight management, improved energy levels, better fitness results, better sleep, etc. Lumen gives you recommendations to improve your metabolic health. It can also track your cycle as well as the onset of menopause, and adjust your recommendations to keep your metabolism healthy through hormonal shifts, so you can keep up your energy and stave off cravings. So, if you want to take the next step in improving your health, go to lumen.me/ROUNDTABLE to get 15 percent off your Lumen.

- Qualia Senolytic: Have you heard about senolytics yet? It's a class of ingredients discovered less than 10 years ago, and it's being called the biggest discovery of our time for promoting healthy aging and enhancing your physical prime. Your goals in your career and beyond require productivity. But let's be honest: The aging process is not our friend when it comes to endless energy and productivity. As we age, everyone accumulates "senescent" cells in their body. Senescent cells cause symptoms of aging, such as aches and discomfort, slow workout recoveries, and sluggish mental and physical energy associated with that "middle age" feeling. Also known as "Zombie Cells," they are old and worn out and not serving a useful function for our health anymore, but they are taking up space and nutrients from our healthy cells. Much like pruning the yellowing and dead leaves off a plant, Qualia Senolytic removes those worn-out senescent cells to allow for the rest of your cells to thrive in the body. Take it just two days a month. The formula is non-GMO, vegan, and gluten-free, and the ingredients are meant to complement one another, factoring in the combined effect of all ingredients together. Resist aging at the cellular level and try Qualia Senolytic. Go to Qualialife.com/ROUNDTABLE for up to 50 percent off and use code ROUNDTABLE at checkout for an additional 15 percent off. For your convenience Qualia Senolytic is also available at select GNC locations near you.

Audio production by Ian Keyser; assistant production by Hunt Beaty.

Music: "Angeline," by The Brothers Steve

- Video Editor: Ian Keyser

- Producer: Hunt Beaty

The post Why Libertarians Hate Kamala Harris' Economic Platform appeared first on Reason.com.