Baltimore's Tax Sales Are Robbing People of Their Equity

Each year, the Edmondson Community Organization (ECO)—a nonprofit in Baltimore dedicated to revitalizing the city's Midtown-Edmondson area—reviews an obscure list of properties released by the government. The task is to see how many are situated within the organization's neighborhood boundaries. The fewer, the better.

The owners of the properties that do appear have fallen behind on their property taxes and, as a result, are poised to lose their real estate in an annual tax sale conducted by the government. After poring over the list, the ECO knocks on those doors to deliver the queasy news and alert the occupants to what is about to happen.

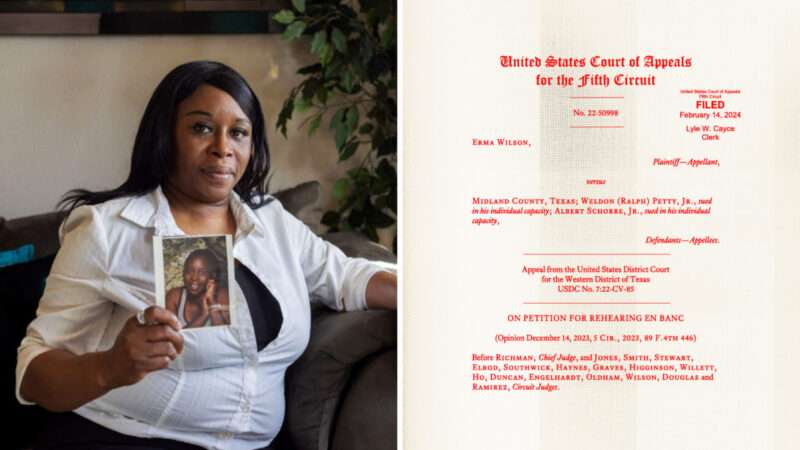

The issue is one ECO knows intimately. A few years back, the organization accrued a $2,543 property tax debt on its community center. So in 2018, the city sold that lien for $5,115 to a California-based investor, who then foreclosed on and sold the ECO's building for $139,500. In return, the ECO got a check for the difference between its debt and the lien purchase price: $2,572.

In other words, all told, the organization paid six figures to compensate for the $2,543 it owed the government, in what a new federal lawsuit alleges is a pervasive practice in Baltimore that illegally deprives people of their equity in violation of the Fifth Amendment's Taking Clause as the city attempts to satisfy modest tax debts.

Every spring, Baltimore bureaucrats conduct a mass auction online to sell off liens like the ECO's. Sometimes the unlucky debtors have fallen just hundreds of dollars behind on their taxes.

For that, they may lose their property and the vast majority of equity tied up in it. Following an investor's purchase, an owner has a certain period to satisfy the amount of the lien, along with interest and fees, to keep their property. That's a tall order when considering these parties were struggling to pay the original debt, much less the new total, which has since ballooned. In the case that debtors are unsuccessful, the investor has effectively purchased the property for the amount they paid for the lien.

In the ECO's case, that meant an investor bought their building for about 2,600 percent less than what it ultimately sold for. The ECO, in turn, was left with a fraction of what their property was worth.

That Baltimore's process robs property owners of huge chunks of equity is not just a regrettable side effect, the ECO's lawsuit alleges; it's baked into the nature of the city's approach. "The City understands there that there is a finite pot of investor capital available to purchase all the liens," reads the complaint. "This creates a perverse incentive for the City to minimize the winning bids"—a.k.a. to depress prices—"to spread that finite pot across the highest number of liens."

Some of the moving parts of Baltimore's approach do seem to imply that the government is not merely unconcerned with owners retaining some of their equity but that they are actively seeking to keep bids low. The more glaring examples included in the ECO's suit show that the city charges a high-bid premium that punishes investors making offers above a certain threshold and opts to fulfill the law's advertising requirement in part by listing properties in The Daily Record, a business and legal newspaper that is not targeted at the general community. (The ECO says this violates state law, which stipulates that such a sale must be advertised twice in general-circulation newspapers.)

"There's a limited amount of investor money out there," says Maryland Legal Aid's chief legal and advocacy director Somil Trivedi, who is representing the ECO, "and the city has structured a system to spread that money across as many liens as possible instead of getting as much equity back for their citizens."

The ECO is not alone, according to the suit, but is one of many victims. You don't have to travel far to find others. "In the same tax sale in which a bidder purchased a lien on ECO's building, 68 properties in Midtown-Edmondson were also subject to the tax sale," states its complaint. "The winning bids on those properties totaled only 22% of the assessed value of the properties—a dramatic loss of generational wealth for the owner of each Midtown-Edmondson property that was lost in the sale."

Home equity theft, as it's sometimes called, was once an obscure issue limited to discussion in magazines like this one. But last year it took the national stage when the Supreme Court ruled unanimously in Tyler v. Hennepin County that a local government had violated the Constitution when it seized an elderly woman's condo over a modest tax debt, sold it, and kept the profit. Geraldine Tyler, the plaintiff in that suit, had fallen $2,300 behind on her taxes, which ultimately reached $15,000 after Hennepin County tacked on penalties, interest, and fees. The government then sold the condo for $40,000 and kept the additional $25,000.

While the ECO's situation isn't entirely analogous to Tyler's—the organization was paid something—Baltimore's scheme could still very well be unconstitutional, says Christina M. Martin, a senior attorney at Pacific Legal Foundation who represented Tyler before the Supreme Court. "If the procedure that you're using to sell the property is designed in a totally unreasonable manner, then obviously people are going to still get robbed of more than what they owe," she tells me. "There's a longstanding history of courts overturning sales that have a shocking result like [the ECO's]."

Tyler, in theory, should have put an end to stories like these. But the lawsuit out of Baltimore comes as some other jurisdictions have devised creative ways to comply with the law on its face but not really in practice. After Michigan's Supreme Court ruled the practice unconstitutional, for example, the state passed a convoluted debt collection statute that requires owners to complete a Herculean legal obstacle course to reclaim their equity. It is a difficult course to win.

"It is the government's choice in the first place to collect property taxes, to decide what regime they want to use to enforce the collection of those property taxes, and so it can't then complain that the regime that it chose to engage in for an amount of money that it chooses to collect is then too difficult to do constitutionally," says Trivedi. "There are lots of jurisdictions around the country that do it differently. Some don't even have tax sales. Some have much longer periods of negotiation and payment plans….Municipalities around the country have figured out ways to collect taxes without doing it unconstitutionally."

The post Baltimore's Tax Sales Are Robbing People of Their Equity appeared first on Reason.com.