Optical Metasurfaces Shine a Light on Li-Fi, Lidar

A new, tunable smart surface can transform a single pulse of light into multiple beams, each aimed in different directions. The proof-of-principle development opens the door to a range of innovations in communications, imaging, sensing, and medicine.

The research comes out of the Caltech lab of Harry Atwater, a professor of applied physics and materials science, and is possible due to a type of nano-engineered material called a metasurface. “These are artificially designed surfaces which basically consist of nanostructured patterns,” says Prachi Thureja, a graduate student in Atwater’s group. “So it’s an array of nanostructures, and each nanostructure essentially allows us to locally control the properties of light.”

The surface can be reconfigured up to millions of times per second to change how it is locally controlling light. That’s rapid enough to manipulate and redirect light for applications in optical data transmission such as optical space communications and Li-Fi, as well as lidar.

“[The metasurface] brings unprecedented freedom in controlling light,” says Alex M.H. Wong, an associate professor of electrical engineering at the City University of Hong Kong. “The ability to do this means one can migrate existing wireless technologies into the optical regime. Li-Fi and LIDAR serve as prime examples.”

Metasurfaces remove the need for lenses and mirrors

Manipulating and redirecting beams of light typically involves a range of conventional lenses and mirrors. These lenses and mirrors might be microscopic in size, but they’re still using optical properties of materials like Snell’s Law, which describes the progress of a wavefront through different materials and how that wavefront is redirected—or refracted—according to the properties of the material itself.

By contrast, the new work offers the prospect of electrically manipulating a material’s optical properties via a semiconducting material. Combined with nano-scaled mirror elements, the flat, microscopic devices can be made to behave like a lens, without requiring lengths of curved or bent glass. And the new metasurface’s optical properties can be switched millions of times per second using electrical signals.

“The difference with our device is by applying different voltages across the device, we can change the profile of light coming off of the mirror, even though physically it’s not moving,” says paper co-author Jared Sisler—also a graduate student in Atwater’s group. “And then we can steer the light like it’s an electrically reprogrammable mirror.”

The device itself, a chip that measures 120 micrometers on each side, achieves its light-manipulating capabilities with an embedded surface of tiny gold antennas in a semiconductor layer of indium tin oxide. Manipulating the voltages across the semiconductor alters the material’s capacity to bend light—also known as its index of refraction. Between the reflection of the gold mirror elements and the tunable refractive capacity of the semiconductor, a lot of rapidly-tunable light manipulation becomes possible.

“I think the whole idea of using a solid-state metasurface or optical device to steer light in space and also use that for encoding information—I mean, there’s nothing like that that exists right now,” Sisler says. “So I mean, technically, you can send more information if you can achieve higher modulation rates. But since it’s kind of a new domain, the performance of our device is more just to show the principle.”

Metasurfaces open up plenty of new possibilities

The principle, says Wong, suggests a wide array of future technologies on the back of what he says are likely near-term metasurface developments and discoveries.

“The metasurface [can] be flat, ultrathin, and lightweight while it attains the functions normally achieved by a series of carefully curved lenses,” Wong says. “Scientists are currently still unlocking the vast possibilities the metasurface has available to us.

“With improvements in nanofabrication, elements with small feature sizes much smaller than the wavelength are now reliably fabricable,” Wong continues. “Many functionalities of the metasurface are being routinely demonstrated, benefiting not just communication but also imaging, sensing, and medicine, among other fields... I know that in addition to interest from academia, various players from industry are also deeply interested and making sizable investments in pushing this technology toward commercialization.”

Santiago Tenorio holds one of Lime Microsystems’ private 5G base-station kits.Vodafone

Santiago Tenorio holds one of Lime Microsystems’ private 5G base-station kits.Vodafone

A Cessna [top left] carried a 38 GHz antenna [top right] during a flight, functioning as a 5G base station for receivers on the ground [bottom right]. The plane was able to connect to multiple ground stations at once [illustration, bottom left].NTT Docomo

A Cessna [top left] carried a 38 GHz antenna [top right] during a flight, functioning as a 5G base station for receivers on the ground [bottom right]. The plane was able to connect to multiple ground stations at once [illustration, bottom left].NTT Docomo

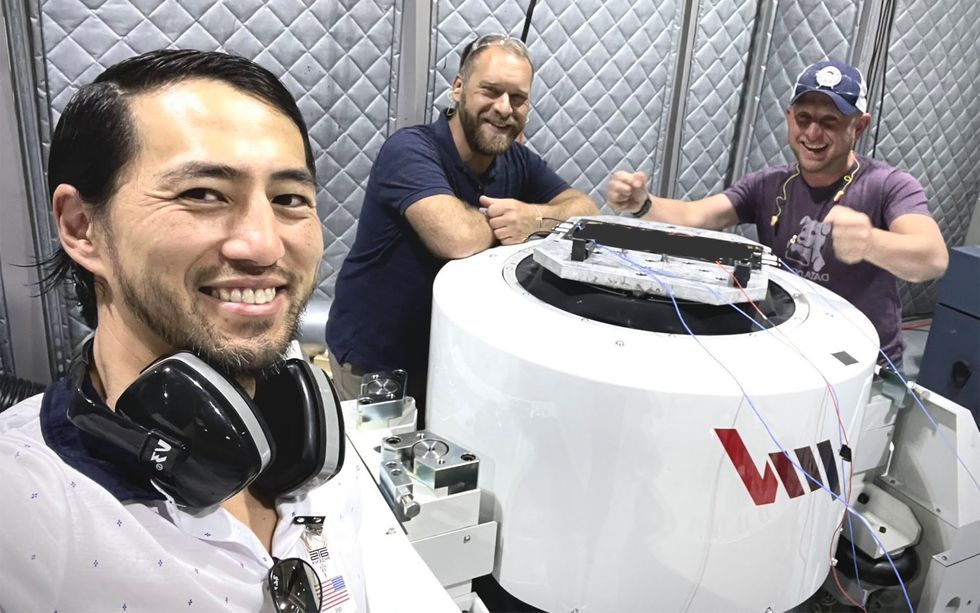

Hubble Network chief space officer John Kim (left) and two company engineers perform tests on the company’s signal-sensing satellite technology. Hubble Network

Hubble Network chief space officer John Kim (left) and two company engineers perform tests on the company’s signal-sensing satellite technology. Hubble Network