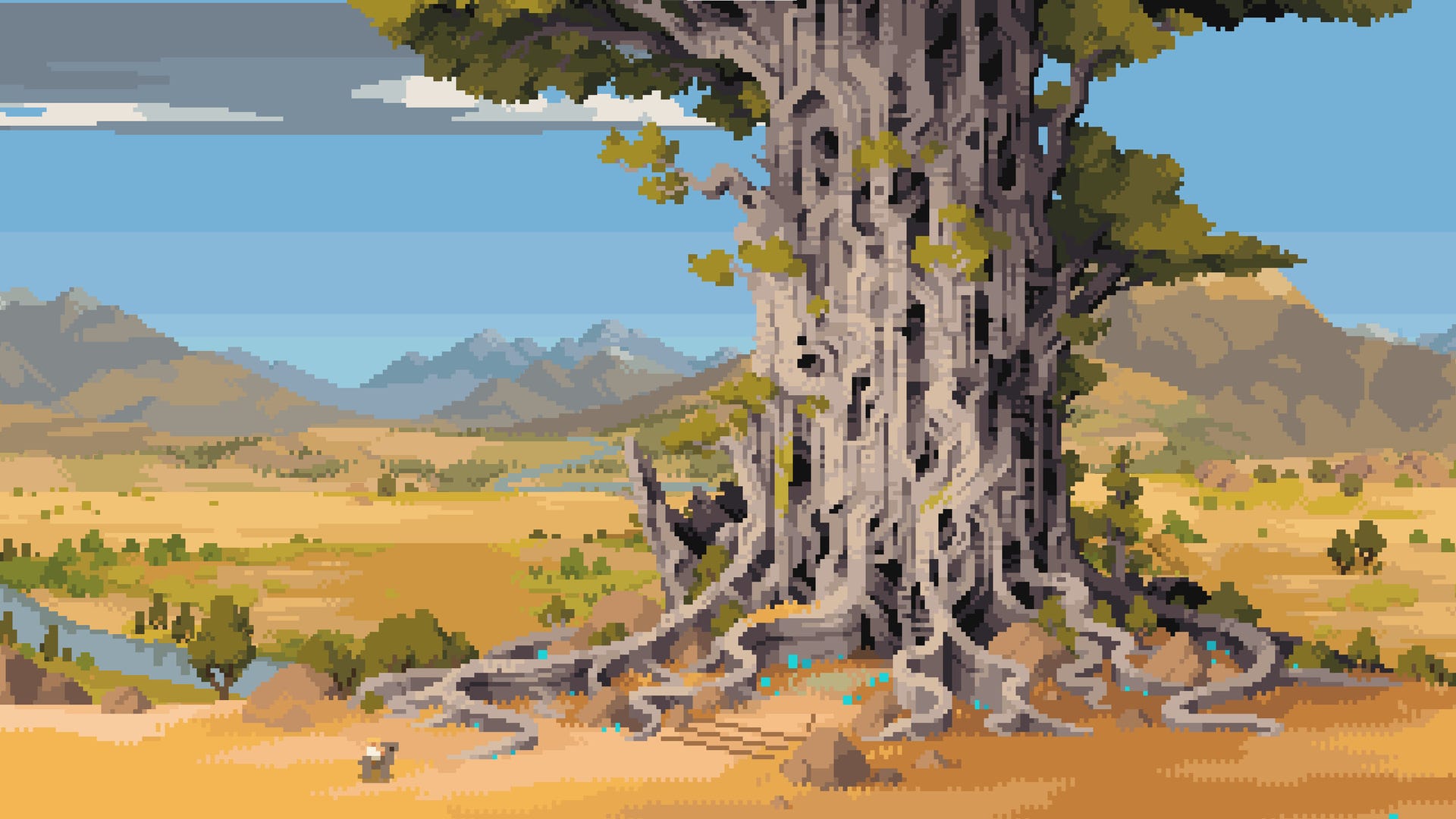

The Plucky Squire offers familiar ideas in a lovely new arrangement

The special, almost intangible loveliness of the Plucky Squire isn't down to either the game design itself or the way it's presented. It's down to both of these things, combined so thoroughly, and with such imagination, that it's hard to stir them apart.

To put it another way, it's not just that this is a fantasy-action game in which your hero receives a bow and arrow from a beautiful elf. It's that, to win that bow and arrow, the hero first has to venture across the authentic wilderness of a child's cluttered bedroom desk, and into a cardboard castle. There, at the top of a tower formed by a stack of beloved books, the hero and the elf must do battle inside the stiff confines of a knock-off Magic: The Gathering card.

This completely rules. And that's just one moment from the preview build of the game I've been playing over the last few days that has elicited such a gasp of wonder and delight. A battle inside a battling card! And then I walk away from it with a golden bow. Yes please, Plucky Squire. Yes please.

_Rwmp6uD.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)