Dear Taylor Swift: There Are Better Ways To Respond To Trump’s AI Images Of You Than A Lawsuit

We’ve written a ton about Taylor Swift’s various adventures in intellectual property law and the wider internet. Given her sheer popularity and presence in pop culture, that isn’t itself particularly surprising. What has been somewhat interesting about her as a Techdirt subject, though, has been how she has straddled the line between being a victim of overly aggressive intellectual property enforcement as well as being a perpetrator of the same. All of this is to say that Swift is not a stranger to negative outcomes in the digital realm, nor is she a stranger to being the legal aggressor.

Which is why the point of this post is to be something of an open letter to Her Swiftness to not listen to roughly half the internet that is clamoring for her to sue Donald Trump for sharing some AI-generated images on social media falsely implying that Swift had endorsed him. First, the facts.

Taylor Swift has yet to endorse any presidential candidate this election cycle. But former President Donald Trump says he accepts the superstar’s non-existent endorsement.

Trump posted “I accept!” on his Truth Social account, along with a carousel of (Swift) images – at least some of which appear to be AI-generated.

One of the AI-manipulated photos depicts Swift as Uncle Sam with the text, “Taylor wants you to vote for Donald Trump.” The other photos depict fans of Swift wearing “Swifties for Trump” T-shirts.

As the quote notes, not all of the images were AI generated “fakes.” At least one of them was from a very real woman, who is very much a Swift fan, wearing a “Swifties for Trump” shirt. There is likewise a social media campaign for supporters from the other side of the aisle, too, “Swifties for Kamala”. None of that is really much of an issue, of course. But the images shared by Trump on Truth Social implied far more than a community of her fans that also like him. So much so, in fact, that he appeared to accept an endorsement that never was.

In case you didn’t notice, immediately below that top left picture is a label that clearly marks the article and associated images as “satire.” The image of Swift doing the Uncle Sam routine to recruit people to back Trump is also obviously not something that came directly from Swift or her people. In fact, while she has not endorsed a candidate in this election cycle (more on that in a moment), Swift endorsed Biden in 2020 with some particularly biting commentary around why she would not vote for Trump.

Now, Trump sharing misleading information on social media is about as newsworthy as the fact that the sun will set tonight. But it is worth noting that social media exploded in response, with a ton of people online advocating Swift to “get her legal team involved” or “sue Trump!” And that is something she absolutely should not do. Some outlets have even suggested that Swift should sue under Tennesse’s new ELVIS Act, which both prohibits the use of people’s voice or image without their authorization, and which has never been tested in court.

Trump’s post might be all it takes to give Swift’s team grounds to sue Trump under Tennessee’s Ensuring Likeness Voice and Image Security Act, or ELVIS Act. The law protects against “just about any unauthorized simulation of a person’s voice or appearance,” said Joseph Fishman, a law professor at Vanderbilt University.

“It doesn’t matter whether an image is generated by AI or not, and it also doesn’t matter whether people are actually confused by it or not,” Fishman said. “In fact, the image doesn’t even need to be fake — it could be a real photo, just so long as the person distributing it knows the subject of the photo hasn’t authorized the use.”

Please don’t do this. First, it probably won’t work. Suing via an untested law that is very likely to run afoul of First Amendment protections is a great way to waste money. Trump also didn’t create the images, presumably, and is merely sharing or re-truthing them. That’s going to make making him liable for them a challenge.

But the larger point here is that all Swift really has to do here is respond, if she chooses, with her own political endorsement or thoughts. It’s not as though she didn’t do so in the last election cycle. If she’s annoyed at what Trump did and wants to punish him, she can solve that with more speech: her own. Hell, there aren’t a ton of people out there who can command an audience that rivals Donald Trump’s… but she almost certainly can!

Just point out that what he shared was fake. Mention, if she wishes, that she voted against him last time. If she likes, she might want to endorse a different candidate. Or she can merely leave it with a biting denial, such as:

“The images Donald Trump shared implied that I have endorsed him. I have not. In fact, I didn’t authorize him to use my image in any way and request that he does not in the future. On the other hand, Donald Trump has a history of not minding much when it comes to getting a woman’s consent, so I won’t get my hopes up too much.”

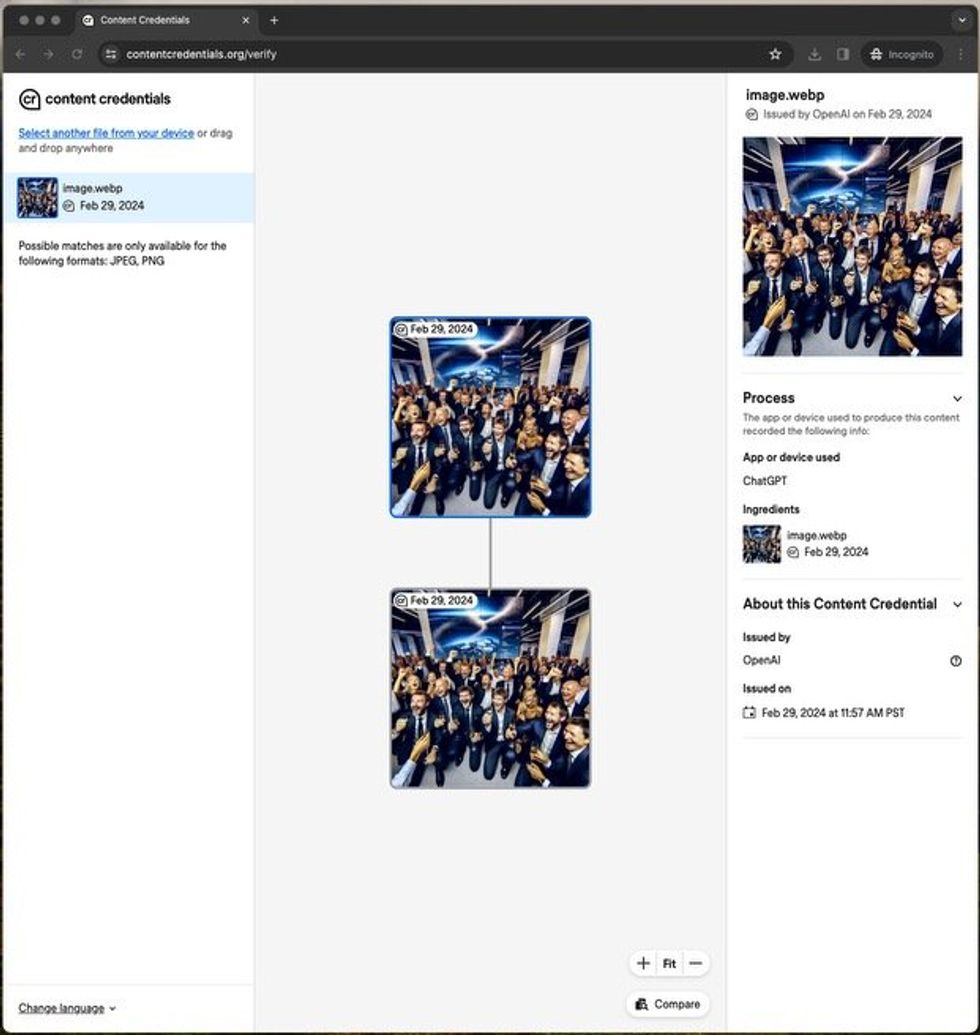

When the authors uploaded an image they’d generated to a website that checks for watermarks, the site correctly stated that it was a synthetic image generated by an OpenAI tool. IEEE Spectrum

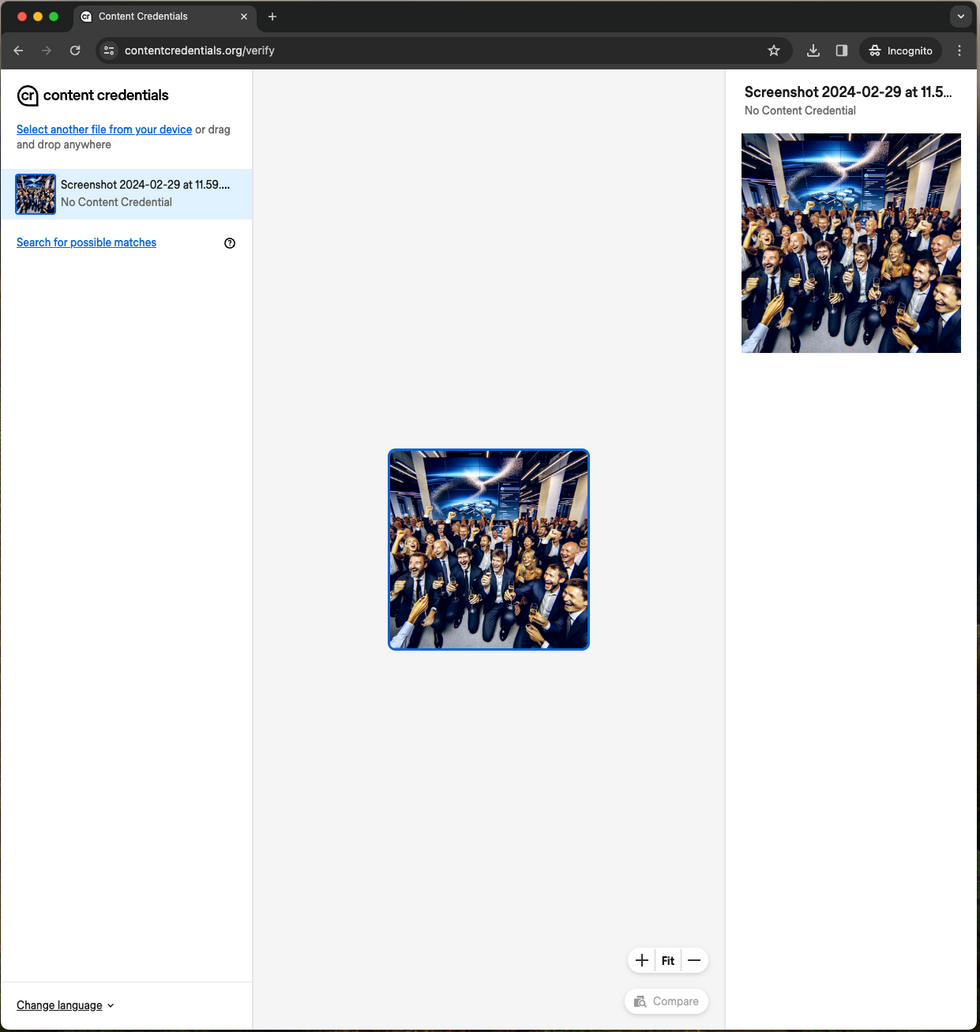

When the authors uploaded an image they’d generated to a website that checks for watermarks, the site correctly stated that it was a synthetic image generated by an OpenAI tool. IEEE Spectrum However, when the authors took a screenshot of the image and uploaded that screenshot to the same verification site, the site found no watermark and therefore no evidence that the image was AI generated. IEEE Spectrum

However, when the authors took a screenshot of the image and uploaded that screenshot to the same verification site, the site found no watermark and therefore no evidence that the image was AI generated. IEEE Spectrum