Censoring the Internet Won't Protect Kids

If good intentions created good laws, there would be no need for congressional debate.

I have no doubt the authors of this bill genuinely want to protect children, but the bill they've written promises to be a Pandora's box of unintended consequences.

The Kids Online Safety Act, known as KOSA, would impose an unprecedented duty of care on internet platforms to mitigate certain harms associated with mental health, such as anxiety, depression, and eating disorders.

While proponents of the bill claim that the bill is not designed to regulate content, imposing a duty of care on internet platforms associated with mental health can only lead to one outcome: the stifling of First Amendment–protected speech.

Today's children live in a world far different from the one I grew up in and I'm the first in line to tell kids to go outside and "touch grass."

With the internet, today's children have the world at their fingertips. That can be a good thing—just about any question can be answered by finding a scholarly article or how-to video with a simple search.

While doctors' and therapists' offices close at night and on weekends, support groups are available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, for people who share similar concerns or have had the same health problems. People can connect, share information, and help each other more easily than ever before. That is the beauty of technological progress.

But the world can also be an ugly place. Like any other tool, the internet can be misused, and parents must be vigilant in protecting their kids online.

It is perhaps understandable that those in the Senate might seek a government solution to protect children from any harms that may result from spending too much time on the internet. But before we impose a drastic, first-of-its-kind legal duty on online platforms, we should ensure that the positive aspects of the internet are preserved. That means we have to ensure that First Amendment rights are protected and that these platforms are provided with clear rules so that they can comply with the law.

Unfortunately, this bill fails to do that in almost every respect.

As currently written, the bill is far too vague, and many of its key provisions are completely undefined.

The bill effectively empowers the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to regulate content that might affect mental health, yet KOSA does not explicitly define the term "mental health disorder." Instead, it references the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders…or "the most current successor edition."

Written that way, not only would someone looking at the law not know what the definition is, but even more concerning, the definition could change without any input from Congress whatsoever.

The scope of one of the most expansive pieces of federal tech legislation could drastically change overnight, and Congress may not even realize it until after it already happened. None of the people's representatives should be comfortable with a definition that effectively delegates Congress's legislative authority to an unaccountable third party.

Second, the bill would impose an unprecedented duty of care on internet platforms to mitigate certain harms, such as anxiety, depression, and eating disorders. But the legislation does not define what is considered harmful to minors, and everyone will have a different belief as to what causes harm, much less how online platforms should go about protecting minors from that harm.

The sponsors of this bill will tell you that they have no desire to regulate content. But the requirement that platforms mitigate undefined harms belies the bill's effect to regulate online content. Imposing a "duty of care" on online platforms to mitigate harms associated with mental health can only lead to one outcome: the stifling of constitutionally protected speech.

For example, if an online service uses infinite scrolling to promote Shakespeare's works, or algebra problems, or the history of the Roman Empire, would any lawmaker consider that harmful?

I doubt it. And that is because website design does not cause harm. It is content, not design, that this bill will regulate.

Last year, Harvard Medical School's magazine published a story entitled "Climate Anxiety; The Existential Threat Posed by Climate Change is Deeply Troubling to Many Young People." That article mentioned that among a "cohort of more than 10,000 people between the ages of 16 and 25, 60 percent described themselves as very worried about the climate and nearly half said the anxiety affects their daily functioning."

The world's most well-known climate activist, Greta Thunberg, famously suffers from climate anxiety. Should platforms stop her from seeing climate-related content because of that?

Under this bill, Greta Thunberg would have been considered a minor and she could have been deprived from engaging online in the debates that made her famous.

Anxiety and eating disorders are two of the undefined harms that this bill expects internet platforms to prevent and mitigate. Are those sites going to allow discussion and debate about the climate? Are they even going to allow discussion about a person's story overcoming an eating disorder? No. Instead, they are going to censor themselves, and users, rather than risk liability.

Would pictures of thin models be tolerated, lest it result in eating disorders for people who see them? What about violent images from war? Should we silence discussions about gun rights because it might cause some people anxiety?

What of online discussion of sexuality? Would pro-gay or anti-gay discussion cause anxiety in teenagers?

What about pro-life messaging? Could pro-life discussions cause anxiety in teenage mothers considering abortion?

In truth, this bill opens the door to nearly limitless content regulation, as people can and will argue that almost any piece of content could contribute to some form of mental health disorder.

In addition, financial concerns may cause online forums to eliminate anxiety-inducing content for all users, regardless of age, if the expense of policing teenage users is prohibitive.

This bill does not merely regulate the internet; it threatens to silence important and diverse discussions that are essential to a free society.

And who is empowered to help make these decisions? That task is entrusted to a newly established speech police. This bill would create a Kids Online Safety Council to help the government decide what constitutes harm to minors and what platforms should have to do to address that harm. These are the types of decisions that should be made by parents and families, not unelected bureaucrats serving as a Censorship Committee.

Those are not the only deficiencies of this bill. The bill seeks to protect minors from beer and gambling ads on certain online platforms, such as Facebook or Hulu. But if those same minors watch the Super Bowl or the PGA tour on TV, they would see those exact same ads.

Does that make any sense? Should we prevent online platforms from showing kids the same content they can and do see on TV every day? Should sports viewership be effectively relegated to the pre-internet age?

And even if it were possible to shield minors from every piece of content that might cause anxiety, depression, or eating disorders, that is still not enough to comply with the KOSA. That is because KOSA requires websites to treat differently individuals that the platform knows or should know are minors.

That means that media platforms who earnestly try to comply with the law could be punished because the government thinks it "should" have known a user was a minor.

This bill, then, does not just apply to minors. A should-have-known standard means that KOSA is an internet-wide regulation, which effectively means that the only way to comply with the law is for platforms to verify ages.

So adults and minors alike better get comfortable with providing a form of ID every time they go online. This knowledge standard destroys the notion of internet privacy.

I've raised several questions about this bill. But no one, not even the sponsors of the legislation, can answer those questions honestly, because they do not know the answer. They do not know how overzealous regulators or state attorneys general will enforce the provisions in this bill. They do not know what rules the FTC may come up with to enforce its provisions.

The inability to answer those questions is the result of several vague provisions of this bill, and once enacted into law, those questions will not be answered by the elected representatives in Congress, they will be answered by bureaucrats who are likely to empower themselves at the expense of our First Amendment rights.

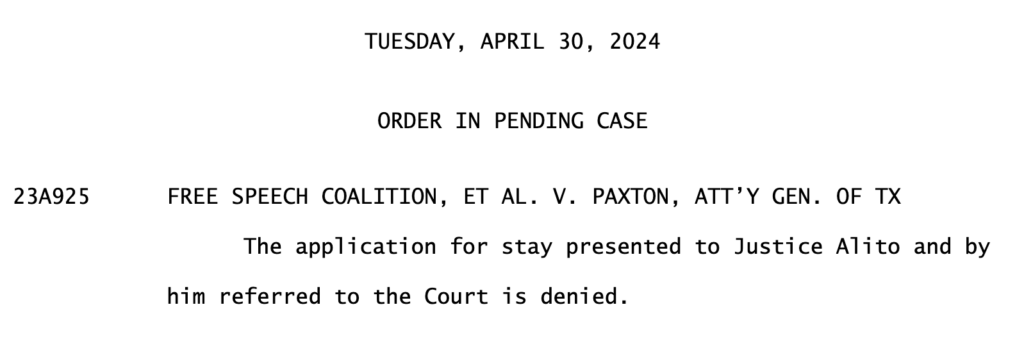

There are good reasons to think that the courts will strike down this bill. They would have a host of reasons to do so. Vagueness pervades this bill. The most meaningful terms are undefined, making compliance with the bill nearly impossible. Even if we discount the many and obvious First Amendment violations inherent in this bill, the courts will likely find this bill void for vagueness.

But we should not rely on the courts to save America from this poorly drafted bill. The Senate should have rejected KOSA and forced the sponsors to at least provide greater clarity in their bill. The Senate, however, was dedicated to passing a KOSA despite its deficiencies.

KOSA contains too many flaws for any one amendment to fix the legislation entirely. But the Senate should have tackled the most glaring problem with KOSA—that it will silence political, social, and religious speech.

My amendment merely stated that no regulations made under KOSA shall apply to political, social, or religious speech. My amendment was intended to address the legitimate concern that this bill threatens free speech online. If the supporters of this legislation really do want to leave content alone, they would have welcomed and supported my amendment to protect political, social, and religious speech.

But that is not what happened. The sponsors of the bill blocked my amendment from consideration and the Senate was prohibited from taking a vote to protect speech.

That should be a lesson about KOSA. The sponsors did not just silence debate in the Senate. Their bill will silence the American people.

KOSA is a Trojan horse. It purports to protect our children by claiming limitless ability to regulate speech and depriving them of the benefits of the internet, which include engaging with like-minded individuals, expressing themselves freely, as well as participating in debates among others with different opinions.

Opposition to this bill is bipartisan, from advocates on the right to the left.

A pro-life organization, Students for Life Action, commented on KOSA, stating, "Once again, a piece of federal legislation with broad powers and vague definitions threatens pro-life speech…those targeted by a weaponized federal government will almost always include pro-life Americans, defending mothers and their children—born and preborn."

Student for Life Action concluded its statement by stating: "Already the pro-life generation faces discrimination, de-platforming, and short and long term bans on social media on the whims of others. Students for Life Action calls for a No vote on KOSA to prevent viewpoint discrimination from becoming federal policy at the FTC."

The ACLU brought more than 300 high school students to Capitol Hill to urge Congress to vote no on KOSA because, to quote the ACLU, "it would give the government the power to decide what content is dangerous to young people, enabling censorship and endangering access to important resources, like gender identity support, mental health materials, and reproductive healthcare."

Government mandates and censorship will not protect children online. The internet may pose new problems, but there is an age-old solution to this issue. Free minds and parental guidance are the best means to protect our children online.

The post Censoring the Internet Won't Protect Kids appeared first on Reason.com.