Scientists want your help finding black holes with your phone

Want to hunt for black holes, but lack access to a mountaintop observatory or deep-space telescope? There’s an app for that—and you can help out astronomers by using it.

Developed by the Dutch Black Hole Consortium, an interdisciplinary research project based in the Netherlands, Black Hole Finder is a free program available both on smartphones and as a desktop website. After reviewing a quick tutorial, all you need to do is study images taken by BlackGEM, a telescope array in Northern Chile tasked with searching the skies for cosmic events called kilonovas. Although launched in March 2024, as Space.com noted on August 19, the project’s recently expanded from just English and Dutch to support Spanish, German, Chinese, Bengali, Polish, and Italian.

Due to the sometimes very high number of transients we have in one night we decided to make things simpler. Everyone who does more than 1000 transients will be granted the Super User status. After that you can help us do a follow up. The follow up process has also been updated. We disabled it a while ago as we were requesting a lot of follow-ups. So many that we ran out of telescope time at LCO. We now have new telescope time available and based on the brightness of the transient you will request a different follow up. Once you reach Super User status you will receive a notification, the tutorial becomes available for you and you can requests follow-ups for transients that are less than 16 hours old.

Formed during the collision of a neutron star and a black hole, kilonovas generate a blinding—but brief—burst of electromagnetic radiation, which sometimes also results in the creation of a stellar-mass black hole. Although 1,000 times brighter than a regular nova, kilonovas are between 1/10th and 1/100th the brightness of their much more well-known relatives, supernovas. This can make them difficult to spot, especially given their comparatively short lifespans. Each accurately identified kilonova offers astronomers a potential location to study further for evidence of newly formed black holes. But given there are thousands of images to peruse and less than 40 people in the Dutch Black Hole Consortium, the organization could use some citizen scientist volunteers.

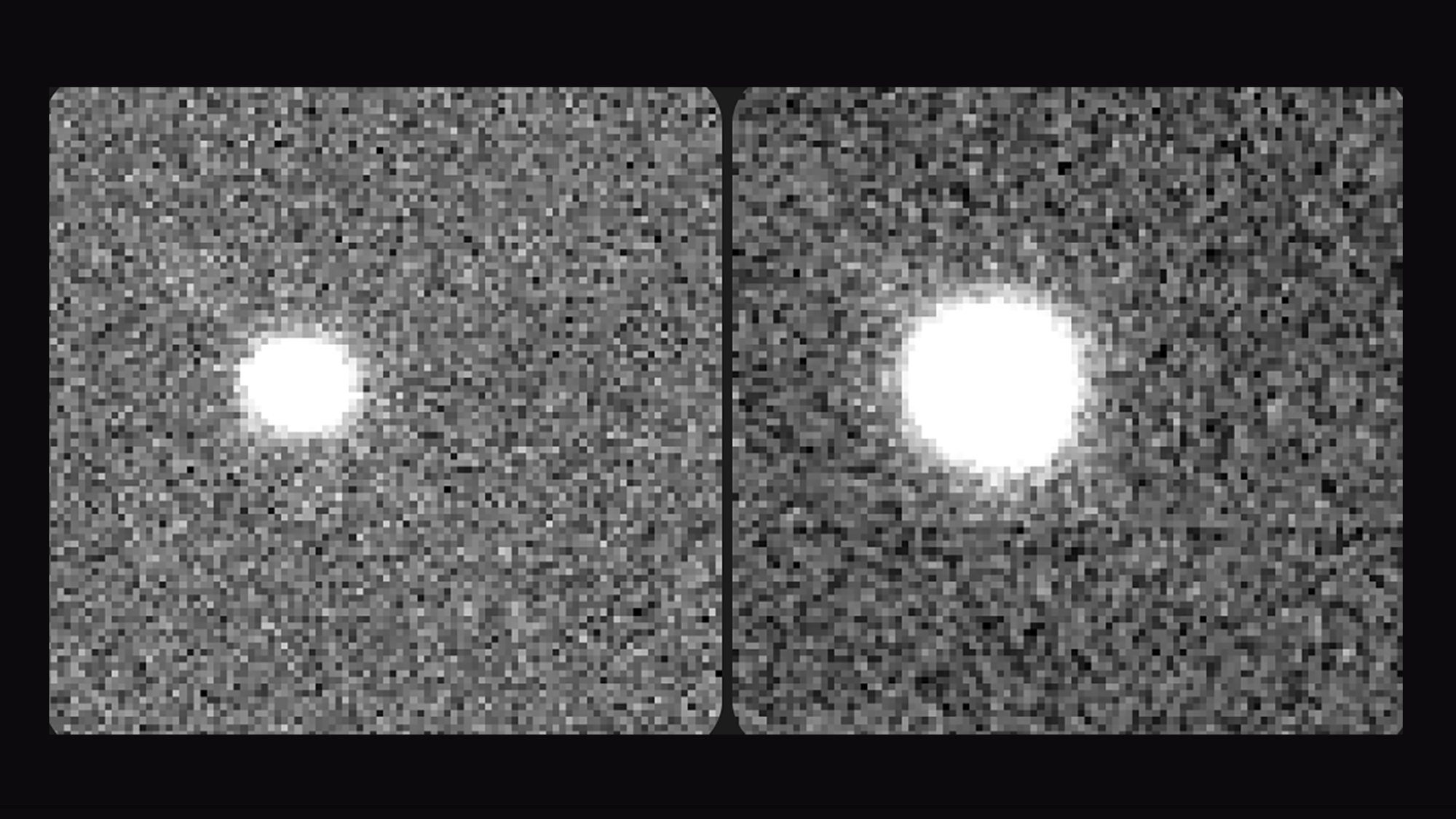

After loading up the app, users are presented with a trio of grainy, black-and-white images of a single focal point—the newest available photo, a reference picture of that same region, and an overlay image displaying the difference between the first two photos. A real kilonova is characterized by a few key details. First off, they are round, extremely white shapes roughly 5-10 pixels in diameter. Comparing the new and reference photos, each kilonova’s brightness can vary in either image, such as fading, growing brighter, completely disappearing, and becoming newly visible.

[Related: Astronomers discover Earth’s closest black hole.]

False positives, however, are pretty identifiable based on their tells. No matter their cause—cosmic-ray interference, reflections, or data processing error—they aren’t rounded like kilonovas, don’t fall within the 5-10 pixel range, and often appear stretched or distorted. After examining each set, users then click whether or not their potential kilonova is “Real” or “Bogus,” and move on to the next entry. Don’t worry, though, if you’re stumped on a particular example, you can simply select “Unknown” to hedge your bets. Black Hole Finder even debuted a new phase on August 1 that opens up the possibility of becoming a “Super User” after reviewing 1,000 or more image sets. Once attained, Super Users can request the newest obtained follow-up images to review.

There’s no high score or prize payout to using the Black Hole Finder, but the knowledge that you are contributing to humanity’s understanding of astrophysics and the cosmos arguably beats bragging rights any day of the week.

The post Scientists want your help finding black holes with your phone appeared first on Popular Science.