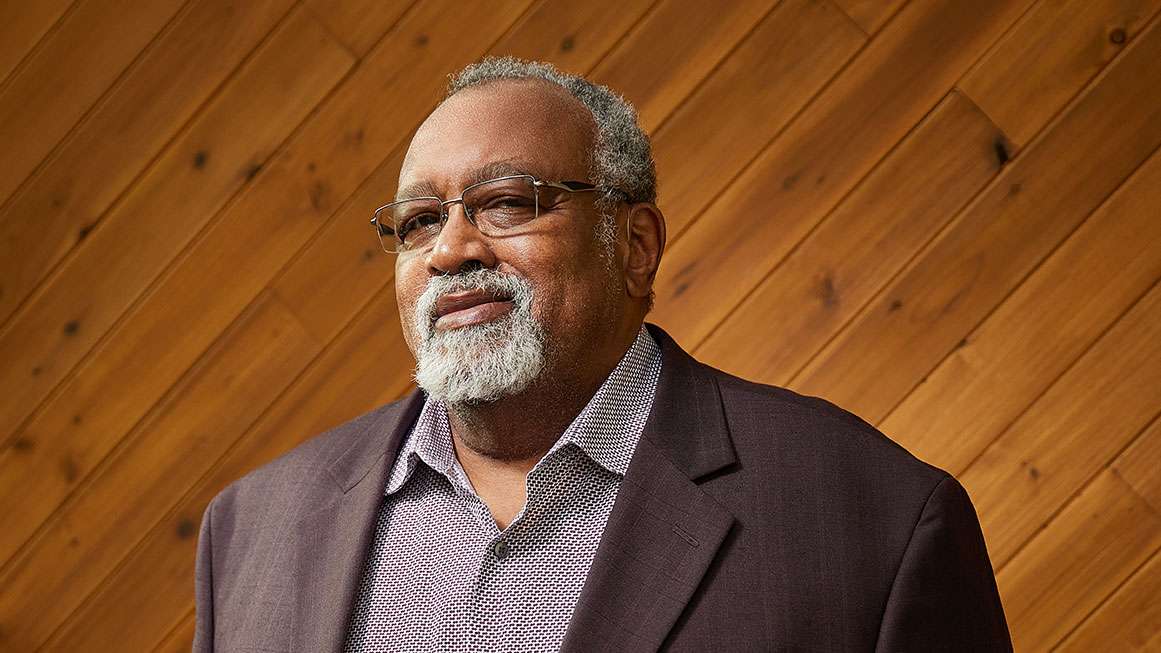

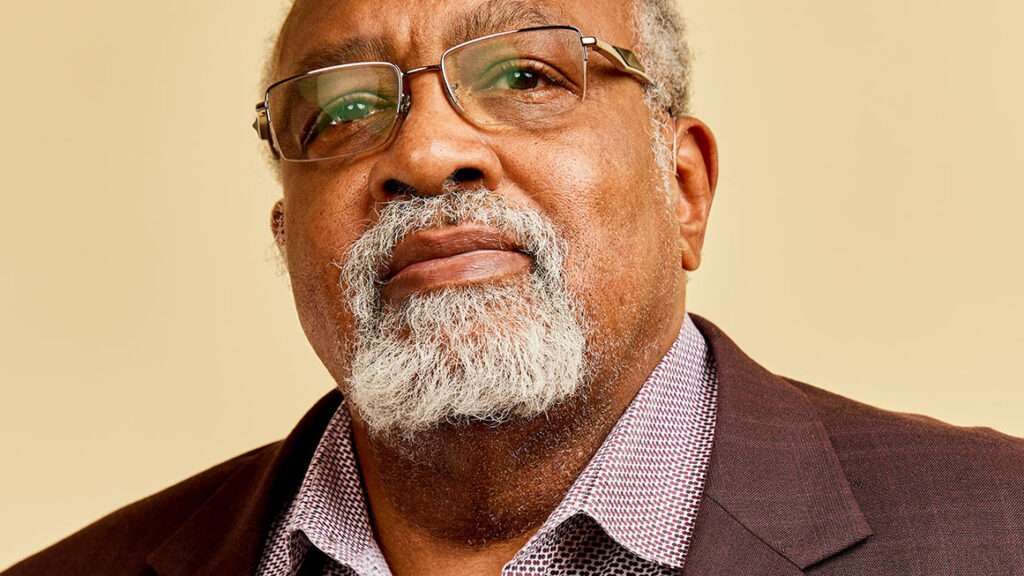

Glenn Loury on Economics, Black Conservatism, and Crack Cocaine

"All you need, besides the cocaine, is a lighter, water, baking soda, some Q-Tips, high-proof alcohol, a ceramic mug, and a piece of cheesecloth or an old T-shirt," writes Glenn Loury in his riveting Late Admissions: Confessions of a Black Conservative. The book is surely the only memoir by an Ivy League economist that includes a recipe for crack cocaine along with technical discussions of Karl Marx, Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich Hayek, and Albert O. Hirschman.

Born in 1948 and raised working class on Chicago's predominantly black South Side, Loury tells a story of self-invention, ambition, hard work, addiction, and redemption that channels Benjamin Franklin's Autobiography, Richard Wright's Native Son, Saul Bellow's The Adventures of Augie March, and Milton Friedman's Capitalism & Freedom. An alternative title might have been "Rise Above It!," the slogan of a pyramid-scheme cosmetics company on which he squandered his savings as a young man in Chicago.

Now a chaired professor at Brown University and the host of The Glenn Show, a wildly popular YouTube offering, Loury worked his way through community college, Northwestern, and a Massachusetts Institute of Technology Ph.D., became the first tenured black economist at Harvard, emerged as a ubiquitous commenter on race and class in the pages of The New Republic and The Atlantic, was offered a post in the Ronald Reagan administration, and was then publicly humiliated after affairs, arrests, and addiction all became public, threatening the end of his professional and personal life. With the support of his wife, Linda Datcher Loury (herself a highly regarded economist), Alcoholics Anonymous (A.A.), and colleagues, Loury managed to rise above it and not just rebuild his academic reputation and relationships with his children, but also gain a unique perspective on economics, individualism, and community.

Reason: When you say you are a black conservative, what does that mean?

Glenn Loury: Well, I think of a few things. One of them is thinking that markets get it right in terms of the resource allocation problem and that the planning instinct and centralized, politically controlled interference in theeconomy is suspect. Of course, there are exceptions. The general predisposition is that I like prices. I like laissez faire. AndI think the first and second fundamental theorems of welfare economics are true, that we get efficient resource allocation when we allow the interplay of self-interest. You know, classical liberal stuff.

That makes you a libertarian, not a conservative.

Well, I was going to go the Edmund Burke route. I was going to say not discarding everything that's been handed to me from the past generations. Respect for tradition, reverence for some of these things that we've been handed down. So when people can't define who's a man and who's a woman, I hold my wallet. I'm a little bit skeptical about this nouveau thing.

But the "black conservative" comes out of I think a reflex or reaction to the dilemma that we African Americans face as the descendants of slaves, a marginal population disadvantaged in various ways and struggling for equality, dignity, inclusion, freedom.

I think there's a trap in that situation: the trap of falling into a status of victim and of looking to the other, the white man, the system to raise our children and deliver us from the challenge which everybody faces of living life in good faith, of, as Jordan Peterson puts it, standing up straight with your shoulders back. Of confronting the reality that there's some stuff that nobody can do for you. This posture of dependence, these arguments for reparations, this invocation of structural and systemic [racism], when the real questions are of responsibility and role.

In your book you cover your education in economics, but it's also a memoir that traffics a lot with addiction, both with drugs and sex. Can economics explain addictive behavior and self-destructive behavior?

Well, I think of the late Gary Becker. He has a paper on addiction. And I think of George Stigler and Becker's classic paper "De Gustibus Non Est Disputandum"—about taste there can be no dispute. They do it all in terms of intertemporal preferences, where you build up a taste for certain kinds of pleasures, and you invest in them.

Did they get it right?

No, I don't think they got it right. I thought it was reductive, closed off. [It's an] "everything's going to be optimization; we just have to find the right objective function" way of looking at the world. I much prefer [game theorist and Nobel laureate] Tom Schelling's engagement with the problems of self-command, as he called it, and addiction, which was understanding the conflict within the single individual who at one point in time would want not to smoke or to use cocaine, but at another point in time would find themselves, notwithstanding their understanding that this is not good for them, being compelled to do it nonetheless, and the strategic interaction between those two types within the same person.

Some critics of capitalism say that drug addiction is the apotheosis of capitalism, that it creates a bunch of things that enslave people. But your story, in one way, is about learning self-command and control over self-destructive behaviors. Is there a larger lesson from your struggles with addiction and your ultimate triumph over it?

Yeah, A.A. saved my life. That therapeutic community, that halfway house I lived in for five months in 1988: They saved my life. I went to meetings faithfully for years. And I abstained. I was clean and sober for five years. But I eventually drifted away from the A.A. abstinence philosophy.

I did have a period where I was very religious. I was born again. This initiated during the period when I was struggling to recover from drug addiction but persisted long after I was out of the woods. It changed my perspective. The hope, the whole experience of going through rehab and what they did, it quieted me down. I started reading the Bible even before I was professing genuine religious conviction. I started memorizing passages after I began to confess some belief, going to meetings, living within myself, a kind of humility. I'm not in control. Let go and let God.

What is the work that you're most proud of as an economist?

I think my best technical paper was published in Econometrica in 1981. It's called "Intergenerational Transfers and the Distribution of Earnings." It applied what at the time were state-of-the-art technical methods in dynamic optimization and the behavior of dynamic stochastic systems to the problem of inequality. It formalized the idea that young people depend on the resources available to their parents, in part, to realize their productive potential as workers and economic agents. Investments made early in life by parents in children affect the productivity of children later in life. That productivity is also dependent on other factors beyond parental control that are random, but it depends on the resources that are available. There cannot be perfect markets to allow for borrowing forward against future earnings potential, so as to realize the investment possibilities. If a parent doesn't have the resources to fund the investment themselves, there's no place to go to borrow to get piano lessons for a kid who might develop into a virtuoso pianist.

As a consequence, inequality has resource allocation consequences. Some parents have a lot of resources; others have very little. But the kids all have comparable potential, and there's diminishing returns to investing in kids. The net result is that if you could move money from rich parents to poor parents and indirectly move investment in kids from rich families to poor families, the loss in the former would outweigh the gain in the latter.

Is that a rebuttal to the idea that you can rise above it on your own? Throughout your work you make a case that if we want a more equitable society, we have to do something to help kids whose parents don't have any resources.

I see them as two different realms of argument about human experience. On the one hand, I'm talking about how there can be market failures and incompleteness and informational impact. Illness and externalities and property rights are unclear, and things like that. And you can make arguments about a minimal role for government intervention to deal with public goods problems and environmental externality problems and perhaps market failures.

On the other hand, if I'm talking to an individual about how to live their life, about whether or not to delegate responsibility for their life to outside forces or to live in good faith, to take responsibility for what you do, that's existential, almost spiritual. It's how to be in the world as opposed to how the world works.

You're on college campuses now, and campuses are more fraught than they ever have been. Do you feel like that message has disappeared?

I think so, especially with the debate that's going on presently about the war in Gaza and the campus protests occupying spaces and setting up tents on the campus green and canceling graduations and seizing buildings and engaging in civil disobedience and whatnot.

But that all comes in the aftermath of the culture war that we've been fighting about critical race theory and diversity, equity, and inclusion. These arguments have been around for a while, and I've tended to be on the side of suspicion of the so-called progressive sentiment. There's too much focus on race and sex and sexuality as identities in the context of the university environment, where our main goal is to acquaint our students with the cultural inheritance of civilization. Their narrow focus on being this particular thing and chopping up the curriculum to make sure that it gets representative treatment feels stifling to me, especially if you let that spill over into what can be said.

The therapeutic sentiment. The kids have these sensibilities. We have to be mindful of them. We don't want to offend. We don't want anyone to be uncomfortable. No, the whole point is to make you uncomfortable. You came thinking something that was really a very superficial and undeveloped framework for thinking; I'm going to expose you to some ideas that run against that grain, and you're going to have to learn how to grapple with them. And in your maturity, you may well return to some of these, but you will do so with a much firmer sense of exactly what it is that you're affirming. I want to educate you. I don't want to placate you. I'm not here to make you feel better.

I do think there's too much reliance on system-based accounts and much less of an embrace of responsibilities that we as individuals have in our education, our politics, our social and economic lives.

What is the case against affirmative action?

The case against affirmative action: It's unfair to people who are disfavored. They didn't do anything to be in the group that you decided you wanted to put your thumb on the scale for. It has concerning incentive problems. If you belong to the favorite group, it's OK to have a B average and be in the 70th percentile of test takers. And you can get into UCLA or Stanford or Yale if you're black. But if you're white, you better have an A-minus average. And you'd better be at the 90th percentile of the test takers.

The systematic implementation of affirmative action amplifies the concerns that one might have about stigmatizing African Americans who would be presumed to be beneficiaries. This is the classic complaint of [Supreme Court Justice] Clarence Thomas, that his Yale law degree isn't worth anything because it's got an asterisk on it because of affirmative action.

There's something undignified about not being held to the same standard as other people and everybody assuming that because of the sufferings of your ancestors you're somehow in need of a special dispensation.I don't regard that as equality. You're not standing on equal ground when you're dependent upon such a dispensation. In the case of affirmative action, it's a Band-Aid. You're treating a symptom and not the underlying cause. The underlying reality is there are population differences in the express[ed] productivity of the agents in question. The African Americans, on average, are producing fewer people in relative numbers who are exhibiting these kinds of skills that your instruments of assessment are intended to measure. And if you don't remedy that problem, you're never going to get truly to equality.

Where are these population differences coming from? Is it primarily an effect of cultural change? Is it inherited differences in economic status and opportunity? Is it genetic?

I don't think it's genetic, though I can't rule out that genetics could have an effect. I'm just not persuaded by the evidence of the early childhood developmental stuff. I don't underestimate the differences in the effectiveness of primary and secondary education. This is not just race. This is race and class and geography and whatnot. I think we'd do ourselves as a society a lot of good if we were to follow the sort of wholesale reform movement in K-12, including charter schools and more competition to the union-dominated public provision sector of that part of our social economy.

But culture is a tough one. I give a lot of evidence indirectly in my memoir about the effects of culture on life experience. The culture that nurtured me coming up in Chicago had its positives. It also had its norms, values, ideals, what a community affirms as being a life well lived, how people spend their time, about parenting, things of this kind.

I read this book by two Asian sociologists, Min Zhou and Jennifer Lee, called The Asian American Achievement Paradox, and it attempts to explain, based on interview data from a couple hundred families in Southern California, how it is that these Asian communities are able to send their youngsters to places like Harvard and Stanford in such large numbers. And it basically makes a cultural argument. One of the chapters is entitled "The Asian F." It turns out that the Asian F is an A-minus, according to some of their respondents. I don't think you can discount the importance of that kind of cultural reinforcement, because at the end of the day what matters is how people spend their time.

You're a critic of race-based policies, but you also get kind of pissed when people dismiss the black experience. You say being a black American is a part of your identity. Is there a way for us to bring our individual cultural and ethnic heritage to the conversation that doesn't divide us or put us in one group or another?

We all have a story. We all have a narrative and a cultural inheritance. And yet underneath we are kind of all the same. Our struggles are comprehensible to each other, and our triumphs and our failures are things that we can relate to as human beings. And that's how we should be relating to each other.

I'm in my 70s now, and I've just written a book about my life. So who am I? What does it amount to? I'm the kid that really did grow up immersed in an almost exclusively black community on the South Side of Chicago. The music that I listened to, the food that I ate, the stories that I was told and that I told to my own children in turn. These things are related to the history, the struggles and triumphs, the dreams and hopes of African-American people. That's a part of who I am. And it annoys me when people attempt to say "get over it" to me. They're not respecting me when they tell me that race is not a deep thing about people.

It's a superficial thing, I grant you that. I grant you the melanin in the skin, the genetic markers that are manifest in my physical presentation, don't add up to very much. But the dreams of my fathers and others, the lore, the narrative about who "we" are, that's not arbitrary and it's not trivial. And it seems to me sociologically naive in the extreme to just want to move past that. That's a part of who people actually are.

But I struggle with this, because I also want to tell my students not to wear that too heavily, not to let it blinker them and prevent them from being able to engage with, for example, the inheritance of European civilization in which we are embedded. That's also your inheritance. Tolstoy is mine. Einstein is mine. And yours. I want to say to youngsters of whatever persuasion: Don't be blinkered. Don't be so parochial that you miss out on the best of what's been written and thought and said in human culture.

This interview has been condensed and edited for style and clarity.

The post Glenn Loury on Economics, Black Conservatism, and Crack Cocaine appeared first on Reason.com.