Kamala Harris' 'Price Gouging' Ban: A New Idea That Has Failed for Thousands of Years

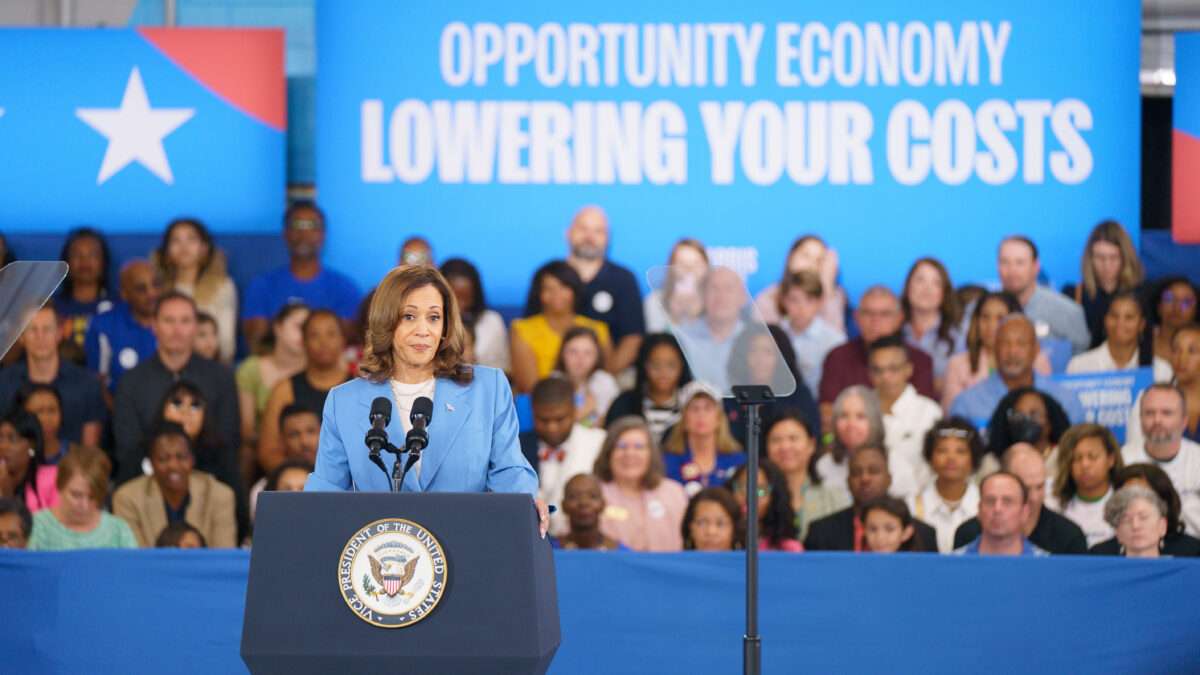

In her first economic policy speech as the 2024 Democratic presidential nominee, Kamala Harris rightly criticized Donald Trump for favoring steep tariffs, saying her Republican opponent "wants to impose what is, in effect, a national sales tax on everyday products and basic necessities that we import from other countries." But in the same speech, Harris pitched a half-baked idea that is just as economically dubious, promising to crack down on "price gouging" by the grocery industry.

That proposal is so misguided that it provoked undisguised skepticism from mainstream news outlets such as CNN, the Associated Press, The New York Times, and The Washington Post, along with criticism by Democratic economists. It showed that Harris joins Trump in pushing populist prescriptions that would hurt consumers in the name of sticking it to supposed economic villains.

"If your opponent claims you're a 'communist,'" Post columnist Catherine Rampell suggested, "maybe don't start with an economic agenda that can (accurately) be labeled as federal price controls." Harvard economist Jason Furman, who chaired President Barack Obama's Council of Economic Advisers, was equally scathing.

"This is not sensible policy, and I think the biggest hope is that it ends up being a lot of rhetoric and no reality," Furman told the Times. "There's no upside here, and there is some downside."

That downside stems from any attempt to override market signals by dictating prices. High prices allocate goods to consumers who derive the greatest value from them, encourage producers to expand supply, and spur competition that helps bring prices down.

Without those signals, you get hoarding and shortages. This is not some airy-fairy theory; it reflects bitter experience since ancient times with interventions like the one Harris proposes.

Consider what happened when President Richard Nixon imposed wage and price controls in the 1970s. "Ranchers stopped shipping their cattle to the market, farmers drowned their chickens, and consumers emptied the shelves of supermarkets," Daniel Yergin and Joseph Stanislaw note in their 1998 book on the rise of free markets.

Or consider what happened more recently with eggs. Thanks to avian flu, Furman noted, "egg prices went up last year" because "there weren't as many eggs," but the high prices encouraged "more egg production." If federal regulators had tried to suppress egg prices, they would have short-circuited that market response.

Harris, of course, says she would target only unjustified price increases, the kind that amount to "illegal price gouging" by "opportunistic companies." But as she emphasizes, there currently is no such thing under federal law, and any attempt to define it would be plagued by subjectivity and a lack of relevant knowledge.

The fact that Harris pins the sharp grocery price inflation of recent years on corporate greed suggests that her judgment about such matters cannot be trusted. Economists generally rate other factors—including the war in Ukraine as well as pandemic-related supply disruptions, shifts in consumer demand, and stimulus spending—as much more important.

High profits, in any event, are another important signal that encourages investment and competition. By forbidding "excessive profits," Harris' proposed price policing would undermine the motivation they provide.

According to the most recent numbers, the annual inflation rate dropped below 3 percent as of July. With inflation cooling, this might seem like a strange time for Harris to resuscitate an idea that was already proving disastrous thousands of years ago. But as the Times notes, her message "polls well with swing voters."

The broad tariffs that Trump favors, which Harris condemns as "a national sales tax" that would "devastate Americans," also poll well in the abstract. But they are popular only until voters consider the consequences.

In a recent Cato Institute survey, for example, 62 percent of respondents favored a tariff on "imported blue jeans," but that number plummeted when they were asked to imagine the resulting price increases. Harris likewise is counting on voters who like what she says but do not contemplate what it would mean in practice.

© Copyright 2024 by Creators Syndicate Inc.

The post Kamala Harris' 'Price Gouging' Ban: A New Idea That Has Failed for Thousands of Years appeared first on Reason.com.