DNA particles that mimic viruses hold promise as vaccines

Using a virus-like delivery particle made from DNA, researchers from MIT and the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard have created a vaccine that can induce a strong antibody response against SARS-CoV-2.

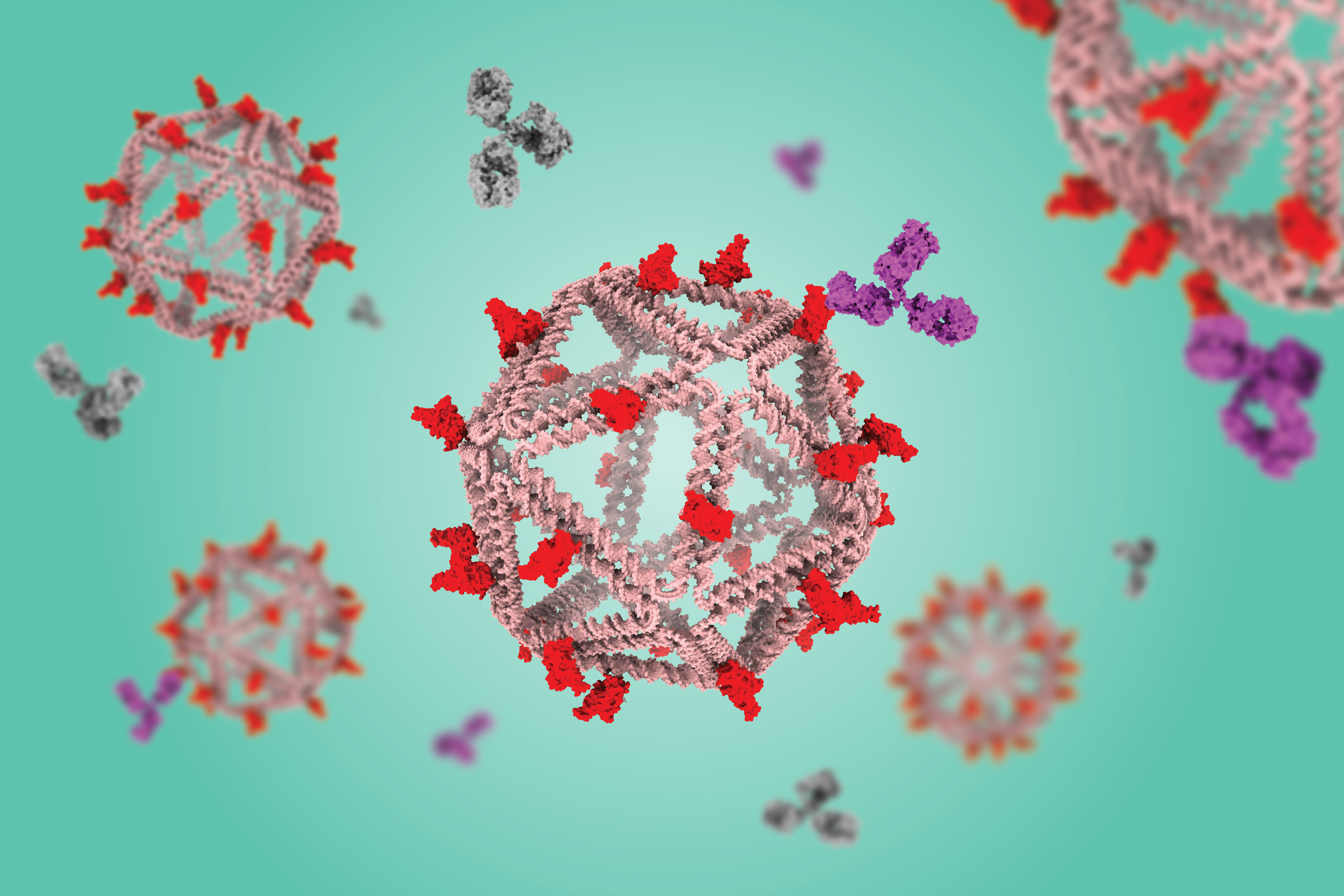

The vaccine, which has been tested in mice, consists of a DNA scaffold that carries many copies of a viral antigen. This type of vaccine, known as a particulate vaccine, mimics the structure of a virus. Most previous work on particulate vaccines has relied on protein scaffolds, but the proteins used in those vaccines tend to generate an unnecessary immune response that can distract the immune system from the target.

In the mouse study, the researchers found that the DNA scaffold does not induce an immune response, allowing the immune system to focus its antibody response on the target antigen.

“DNA, we found in this work, does not elicit antibodies that may distract away from the protein of interest,” says Mark Bathe, an MIT professor of biological engineering. “What you can imagine is that your B cells and immune system are being fully trained by that target antigen, and that’s what you want — for your immune system to be laser-focused on the antigen of interest.”

This approach, which strongly stimulates B cells (the cells that produce antibodies), could make it easier to develop vaccines against viruses that have been difficult to target, including HIV and influenza, as well as SARS-CoV-2, the researchers say. Unlike T cells, which are stimulated by other types of vaccines, these B cells can persist for decades, offering long-term protection.

“We’re interested in exploring whether we can teach the immune system to deliver higher levels of immunity against pathogens that resist conventional vaccine approaches, like flu, HIV, and SARS-CoV-2,” says Daniel Lingwood, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School and a principal investigator at the Ragon Institute. “This idea of decoupling the response against the target antigen from the platform itself is a potentially powerful immunological trick that one can now bring to bear to help those immunological targeting decisions move in a direction that is more focused.”

Bathe, Lingwood, and Aaron Schmidt, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School and principal investigator at the Ragon Institute, are the senior authors of the paper, which appears today in Nature Communications. The paper’s lead authors are Eike-Christian Wamhoff, a former MIT postdoc; Larance Ronsard, a Ragon Institute postdoc; Jared Feldman, a former Harvard University graduate student; Grant Knappe, an MIT graduate student; and Blake Hauser, a former Harvard graduate student.

Mimicking viruses

Particulate vaccines usually consist of a protein nanoparticle, similar in structure to a virus, that can carry many copies of a viral antigen. This high density of antigens can lead to a stronger immune response than traditional vaccines because the body sees it as similar to an actual virus. Particulate vaccines have been developed for a handful of pathogens, including hepatitis B and human papillomavirus, and a particulate vaccine for SARS-CoV-2 has been approved for use in South Korea.

These vaccines are especially good at activating B cells, which produce antibodies specific to the vaccine antigen.

“Particulate vaccines are of great interest for many in immunology because they give you robust humoral immunity, which is antibody-based immunity, which is differentiated from the T-cell-based immunity that the mRNA vaccines seem to elicit more strongly,” Bathe says.

A potential drawback to this kind of vaccine, however, is that the proteins used for the scaffold often stimulate the body to produce antibodies targeting the scaffold. This can distract the immune system and prevent it from launching as robust a response as one would like, Bathe says.

“To neutralize the SARS-CoV-2 virus, you want to have a vaccine that generates antibodies toward the receptor binding domain portion of the virus’ spike protein,” he says. “When you display that on a protein-based particle, what happens is your immune system recognizes not only that receptor binding domain protein, but all the other proteins that are irrelevant to the immune response you’re trying to elicit.”

Another potential drawback is that if the same person receives more than one vaccine carried by the same protein scaffold, for example, SARS-CoV-2 and then influenza, their immune system would likely respond right away to the protein scaffold, having already been primed to react to it. This could weaken the immune response to the antigen carried by the second vaccine.

“If you want to apply that protein-based particle to immunize against a different virus like influenza, then your immune system can be addicted to the underlying protein scaffold that it’s already seen and developed an immune response toward,” Bathe says. “That can hypothetically diminish the quality of your antibody response for the actual antigen of interest.”

As an alternative, Bathe’s lab has been developing scaffolds made using DNA origami, a method that offers precise control over the structure of synthetic DNA and allows researchers to attach a variety of molecules, such as viral antigens, at specific locations.

In a 2020 study, Bathe and Darrell Irvine, an MIT professor of biological engineering and of materials science and engineering, showed that a DNA scaffold carrying 30 copies of an HIV antigen could generate a strong antibody response in B cells grown in the lab. This type of structure is optimal for activating B cells because it closely mimics the structure of nano-sized viruses, which display many copies of viral proteins in their surfaces.

“This approach builds off of a fundamental principle in B-cell antigen recognition, which is that if you have an arrayed display of the antigen, that promotes B-cell responses and gives better quantity and quality of antibody output,” Lingwood says.

“Immunologically silent”

In the new study, the researchers swapped in an antigen consisting of the receptor binding protein of the spike protein from the original strain of SARS-CoV-2. When they gave the vaccine to mice, they found that the mice generated high levels of antibodies to the spike protein but did not generate any to the DNA scaffold.

In contrast, a vaccine based on a scaffold protein called ferritin, coated with SARS-CoV-2 antigens, generated many antibodies against ferritin as well as SARS-CoV-2.

“The DNA nanoparticle itself is immunogenically silent,” Lingwood says. “If you use a protein-based platform, you get equally high titer antibody responses to the platform and to the antigen of interest, and that can complicate repeated usage of that platform because you’ll develop high affinity immune memory against it.”

Reducing these off-target effects could also help scientists reach the goal of developing a vaccine that would induce broadly neutralizing antibodies to any variant of SARS-CoV-2, or even to all sarbecoviruses, the subgenus of virus that includes SARS-CoV-2 as well as the viruses that cause SARS and MERS.

To that end, the researchers are now exploring whether a DNA scaffold with many different viral antigens attached could induce broadly neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and related viruses.

The research was primarily funded by the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, and the Fast Grants program.

© Credit: The Bathe Lab