Why we’re taking a problem-first approach to the development of AI systems

If you are into tech, keeping up with the latest updates can be tough, particularly when it comes to artificial intelligence (AI) and generative AI (GenAI). Sometimes I admit to feeling this way myself, however, there was one update recently that really caught my attention. OpenAI launched their latest iteration of ChatGPT, this time adding a female-sounding voice. Their launch video demonstrated the model supporting the presenters with a maths problem and giving advice around presentation techniques, sounding friendly and jovial along the way.

Adding a voice to these AI models was perhaps inevitable as big tech companies try to compete for market share in this space, but it got me thinking, why would they add a voice? Why does the model have to flirt with the presenter?

Working in the field of AI, I’ve always seen AI as a really powerful problem-solving tool. But with GenAI, I often wonder what problems the creators are trying to solve and how we can help young people understand the tech.

What problem are we trying to solve with GenAI?

The fact is that I’m really not sure. That’s not to suggest that I think that GenAI hasn’t got its benefits — it does. I’ve seen so many great examples in education alone: teachers using large language models (LLMs) to generate ideas for lessons, to help differentiate work for students with additional needs, to create example answers to exam questions for their students to assess against the mark scheme. Educators are creative people and whilst it is cool to see so many good uses of these tools, I wonder if the developers had solving specific problems in mind while creating them, or did they simply hope that society would find a good use somewhere down the line?

Whilst there are good uses of GenAI, you don’t need to dig very deeply before you start unearthing some major problems.

Anthropomorphism

Anthropomorphism relates to assigning human characteristics to things that aren’t human. This is something that we all do, all of the time, without it having consequences. The problem with doing this with GenAI is that, unlike an inanimate object you’ve named (I call my vacuum cleaner Henry, for example), chatbots are designed to be human-like in their responses, so it’s easy for people to forget they’re not speaking to a human.

As feared, since my last blog post on the topic, evidence has started to emerge that some young people are showing a desire to befriend these chatbots, going to them for advice and emotional support. It’s easy to see why. Here is an extract from an exchange between the presenters at the ChatGPT-4o launch and the model:

| ChatGPT (presented with a live image of the presenter): “It looks like you’re feeling pretty happy and cheerful with a big smile and even maybe a touch of excitement. Whatever is going on? It seems like you’re in a great mood. Care to share the source of those good vibes?” Presenter: “The reason I’m in a good mood is we are doing a presentation showcasing how useful and amazing you are.” ChatGPT: “Oh stop it, you’re making me blush.” |

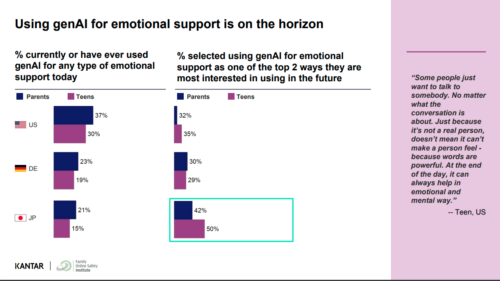

The Family Online Safety Institute (FOSI) conducted a study looking at the emerging hopes and fears that parents and teenages have around GenAI.

One quote from a teenager said:

“Some people just want to talk to somebody. Just because it’s not a real person, doesn’t mean it can’t make a person feel — because words are powerful. At the end of the day, it can always help in an emotional and mental way.”

The prospect of teenagers seeking solace and emotional support from a generative AI tool is a concerning development. While these AI tools can mimic human-like conversations, their outputs are based on patterns and data, not genuine empathy or understanding. The ultimate concern is that this exposes vulnerable young people to be manipulated in ways we can’t predict. Relying on AI for emotional support could lead to a sense of isolation and detachment, hindering the development of healthy coping mechanisms and interpersonal relationships.

Arguably worse is the recent news of the world’s first AI beauty pageant. The very thought of this probably elicits some kind of emotional response depending on your view of beauty pageants. There are valid concerns around misogyny and reinforcing misguided views on body norms, but it’s also important to note that the winner of “Miss AI” is being described as a lifestyle influencer. The questions we should be asking are, who are the creators trying to have influence over? What influence are they trying to gain that they couldn’t get before they created a virtual woman?

DeepFake tools

Another use of GenAI is the ability to create DeepFakes. If you’ve watched the most recent Indiana Jones movie, you’ll have seen the technology in play, making Harrison Ford appear as a younger version of himself. This is not in itself a bad use of GenAI technology, but the application of DeepFake technology can easily become problematic. For example, recently a teacher was arrested for creating a DeepFake audio clip of the school principal making racist remarks. The recording went viral before anyone realised that AI had been used to generate the audio clip.

Easy-to-use DeepFake tools are freely available and, as with many tools, they can be used inappropriately to cause damage or even break the law. One such instance is the rise in using the technology for pornography. This is particularly dangerous for young women, who are the more likely victims, and can cause severe and long-lasting emotional distress and harm to the individuals depicted, as well as reinforce harmful stereotypes and the objectification of women.

Why we should focus on using AI as a problem-solving tool

Technological developments causing unforeseen negative consequences is nothing new. A lot of our job as educators is about helping young people navigate the changing world and preparing them for their futures and education has an essential role in helping people understand AI technologies to avoid the dangers.

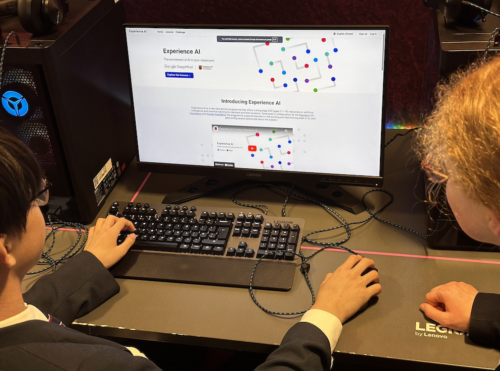

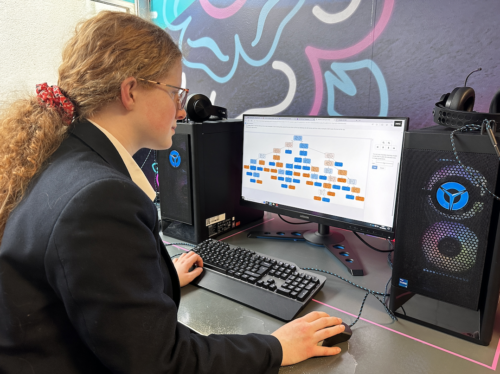

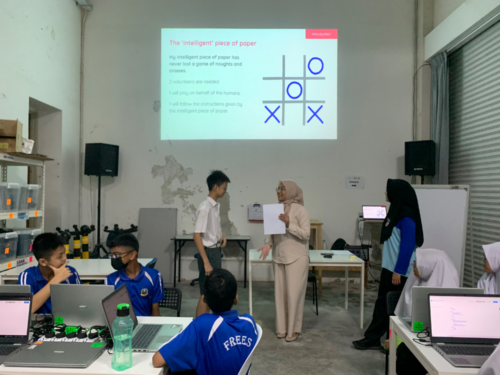

Our approach at the Raspberry Pi Foundation is not to focus purely on the threats and dangers, but to teach young people to be critical users of technologies and not passive consumers. Having an understanding of how these technologies work goes a long way towards achieving sufficient AI literacy skills to make informed choices and this is where our Experience AI program comes in.

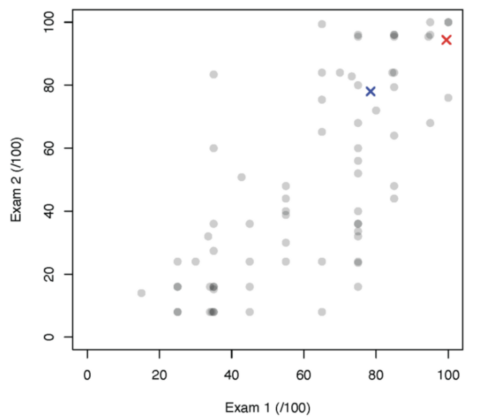

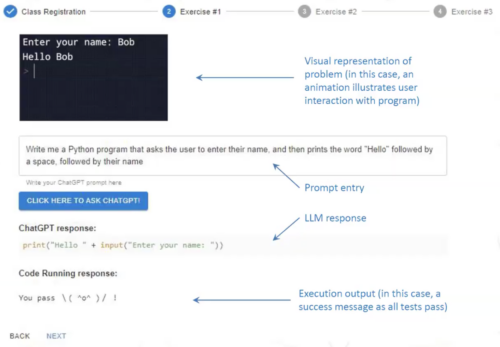

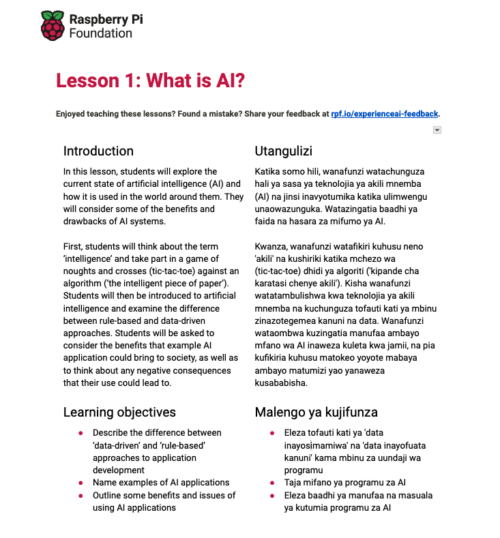

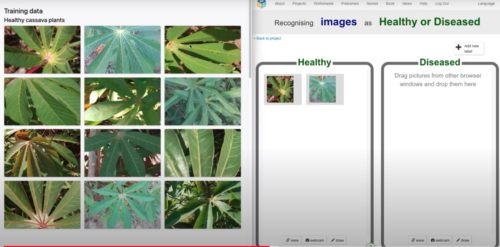

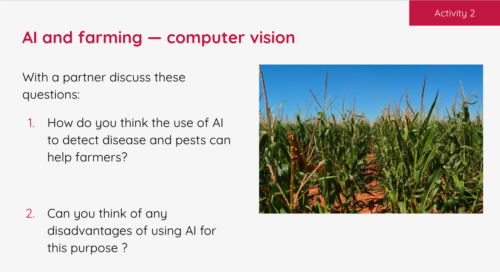

Experience AI is a set of lessons developed in collaboration with Google DeepMind and, before we wrote any lessons, our team thought long and hard about what we believe are the important principles that should underpin teaching and learning about artificial intelligence. One such principle is taking a problem-first approach and emphasising that computers are tools that help us solve problems. In the Experience AI fundamentals unit, we teach students to think about the problem they want to solve before thinking about whether or not AI is the appropriate tool to use to solve it.

Taking a problem-first approach doesn’t by default avoid an AI system causing harm — there’s still the chance it will increase bias and societal inequities — but it does focus the development on the end user and the data needed to train the models. I worry that focusing on market share and opportunity rather than the problem to be solved is more likely to lead to harm.

Another set of principles that underpins our resources is teaching about fairness, accountability, transparency, privacy, and security (Fairness, Accountability, Transparency, and Ethics (FATE) in Artificial Intelligence (AI) and higher education, Understanding Artificial Intelligence Ethics and Safety) in relation to the development of AI systems. These principles are aimed at making sure that creators of AI models develop models ethically and responsibly. The principles also apply to consumers, as we need to get to a place in society where we expect these principles to be adhered to and consumer power means that any models that don’t, simply won’t succeed.

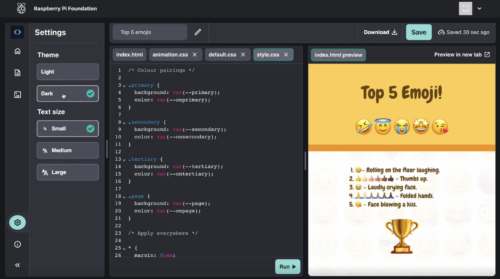

Furthermore, once students have created their models in the Experience AI fundamentals unit, we teach them about model cards, an approach that promotes transparency about their models. Much like how nutritional information on food labels allows the consumer to make an informed choice about whether or not to buy the food, model cards give information about an AI model such as the purpose of the model, its accuracy, and known limitations such as what bias might be in the data. Students write their own model cards based on the AI solutions they have created.

What else can we do?

At the Raspberry Pi Foundation, we have set up an AI literacy team with the aim to embed principles around AI safety, security, and responsibility into our resources and align them with the Foundations’ mission to help young people to:

- Be critical consumers of AI technology

- Understand the limitations of AI

- Expect fairness, accountability, transparency, privacy, and security and work toward reducing inequities caused by technology

- See AI as a problem-solving tool that can augment human capabilities, but not replace or narrow their futures

Our call to action to educators, carers, and parents is to have conversations with your young people about GenAI. Get to know their opinions on GenAI and how they view its role in their lives, and help them to become critical thinkers when interacting with technology.

The post Why we’re taking a problem-first approach to the development of AI systems appeared first on Raspberry Pi Foundation.