The Collective-Action Constitution in an Era of Polarization and Animosity: An Elegy?

The study conducted by The Collective-Action Constitution offers several lessons. First, when states disagree about the existence or severity of collective-action problems, such problems do not simply exist or not in a technical, scientific way. Cost-benefit collective-action problems have an objective structure, but their existence and significance require assessing the extent to which states are externalizing costs that are greater than the benefits they are internalizing, and such assessments may require normative judgments in addition to factfinding.

Second, the assessor that matters most is either the Constitution itself or the governmental institution with the most democratic legitimacy to make such judgment calls. This institution is Congress—the first branch of government—where all states and all Americans are represented, in contrast to individual state governments, where only one state and some Americans are represented. In McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), Chief Justice Marshall explained this key difference between the democratic legitimacy of the states and the people collectively in Congress and the democratic legitimacy of states individually outside it. Congress is also more broadly representative of all states and all people than is the presidency, which does not include both political parties at a given time, or balance interests to anywhere near the same extent that Congress does.

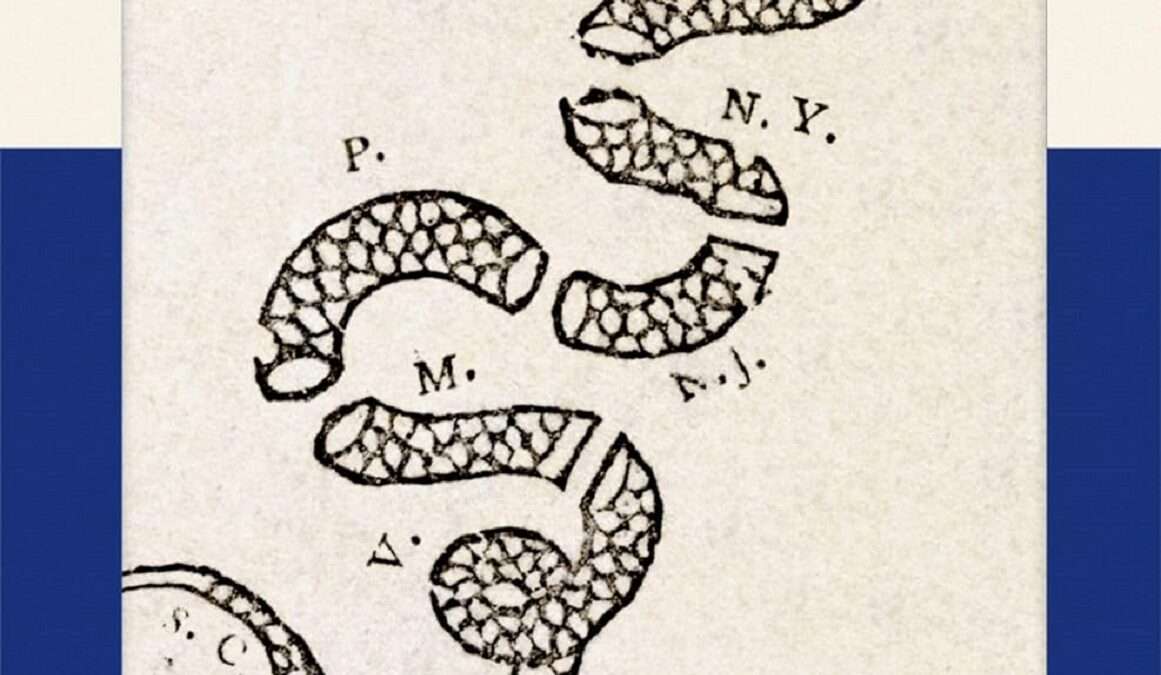

Third, if it is acting within its enumerated powers, Congress need only comply with the voting rules set forth in the Constitution; Congress need not first establish that all or most states agree that a collective-action problem exists and is sufficiently serious to warrant federal regulation. In other words, Congress need not poll states apart from establishing sufficient support in the federal legislative process. Because states are represented in Congress—because congressional majorities represent (albeit imperfectly) the constitutionally relevant views of the states collectively—proceeding otherwise would overrepresent the states, effectively letting them vote twice. One main reason that the Constitution is too difficult to amend, Chapter 10 argues, is that Article V essentially lets states vote twice.

Fourth, Congress's central role in deciding whether and how to solve collective-action problems for the states connects constitutional provisions, principles, and ideas that may otherwise seem to have little to do with one another. These include, for example, the Interstate Compacts Clause (see Chapter 3), the Interstate Commerce Clause (Chapter 5), the congressional approval exception to the dormant commerce principle (Chapter 5), Article III's opening clause, which lets Congress decide whether to create lower federal courts (Chapter 7), Article IV's provisions expressly or implicitly authorizing Congress to legislate (Chapter 8), and democratic-process rights and theory (Chapter 9).

Congress's paramount role in the constitutional scheme raises questions (explored in Part III of the book) about the operation of the Constitution's system of separated and interrelated powers in contemporary times. It is one thing to argue that the Constitution was originally intended, and designed, to render the federal government operating through (super)majority rule more likely to solve multistate collective-action problems than the states operating through unanimity rule. It is another thing to show that this is generally true in practice. As George Washington implied in his letter accompanying submission of the U.S. Constitution to the Confederation Congress that begins The Collective-Action Constitution, to protect state autonomy and individual liberty, the Framers created a bicameral legislature and a separation-of-powers system, both of which make it more difficult to legislate than in a unicameral legislature and a parliamentary system. But the Framers did not imagine that the availability of veto threats would come to dominate the policymaking process in situations having nothing to do with perceived encroachments on the presidency or bills that the president thinks unconstitutional. Nor were the Framers responsible for modern subconstitutional "veto gates" in Congress, especially the Senate filibuster, which makes it even harder to legislate. Finally, the Framers did not foresee the polarized, antagonistic nature of contemporary American politics.

These developments have meant that bicameralism and the separation (and interrelation) of powers often do not merely qualify Congress's ability to legislate. The horizontal structure and contemporary politics likely make it too hard for Congress to do so, particularly given the magnitude and geographic scope of the problems facing the nation and the extent to which Americans look mainly to the federal government, not the states, to solve them. The Constitution's greatest defect in modern times is probably that Congress often cannot execute its legislative responsibilities in the constitutional scheme. A result has been power shifts from Congress to the executive branch, the federal courts, and the states. The main workaround for congressional gridlock has been more frequent unilateral action by the executive. Other partial and potentially worrisome workarounds include efforts by federal courts to "update" the meaning of federal statutes and greater exercises of state regulatory authority. Sufficient solutions to the problem of gridlock may not exist any time soon given the practical impossibility of amending the Constitution, the unlikelihood that veto practice will become more restrained, and the long periods required for political realignments to occur. Ending the legislative filibuster in the Senate by majority vote would, however, have the likely salutary (but not cost-free) consequence of changing the typical voting threshold in this chamber from a three-fifths supermajority to majority rule.

Given the difficulty of legislating in the current era, it might be thought that The Collective-Action Constitution offers an elegy—an account of how the U.S. constitutional system was supposed to function or used to function but functions no longer. To readers who regard the book as an elegy during an era of presidential administration, judicial supremacy, and assertive state legislation, I offer the words of Richard Hooker, who long ago deemed his own book an elegy and justified writing it anyway: "Though for no other cause, yet for this; that posterity may know we have not loosely through silence permitted things to pass away as in a dream." (My learned colleague, H. Jefferson Powell, furnished this quote.)

In truth, however, The Collective-Action Constitution does not offer an elegy. The constitutional structure still has much to commend it relative to relying on the states to act collectively outside Congress. When problems are national or international in scope, the relevant comparison is not between Congress's ability to combat a problem and one state's ability to do so, but between the ability of the political branches to act and the ability of the states to act collectively through unanimous agreement. Collective-action problems would almost certainly be more severe if the federal government were dissolved and states had to unanimously agree to protect the environment; regulate interstate and foreign commerce; build interstate infrastructure; conclude international agreements; contribute revenue to a common treasury and troops to a common military (or coordinate separate militaries); disburse funds held in common; respond to economic downturns; provide a minimum safety net; and handle pandemics, among many other problems. Congress still legislates today, and it does so much more frequently than most (let alone all) states form interstate compacts.

As for the executive branch, Presidents lack the ability to legislate in a formal and legitimate fashion, and so they cannot address the above problems and those with a similar structure to anywhere near the same extent that Congress can. Presidential action is less enduring and far reaching than legislation. Normatively, moreover, executive unilateralism poses risks of democratic deficits and backsliding that congressional power does not.

The federal judiciary's most important job is largely (although not entirely) to get out of the way. The Collective-Action Constitution cautions the U.S. Supreme Court and lower federal courts—both of which can be substantially more assertive than the Founders envisioned in reviewing the constitutionality of federal laws (see Chapter 7)—not to significantly restrict federal power in the years ahead, whether through constitutional-law holdings contracting congressional power or administrative-law decisions diminishing agency power. The nation will continue to face pressing problems that spill across state (or national) borders, so federal action will be needed to address them effectively. In general, the federal government has the authority to act. And given the horizontal structure and the era of partisan polarization and animosity in which Americans will continue to live, there are already major impediments to the ability and willingness of members of Congress to overcome their own collective-action problems and legislate. Especially in modern times, legal doctrine should facilitate, not impede, realization of the Constitution's main structural purpose—its commitment to collective action.

The post The Collective-Action Constitution in an Era of Polarization and Animosity: An Elegy? appeared first on Reason.com.