Not Even A Video Game Can Convince Me To Read The Directions First

We had these report cards in elementary school that, in addition to grading us on school subjects, also evaluated how we were doing on general life skills. I did pretty well in classes besides math, but the two skills I repeatedly failed were “penmanship” and “following directions.” I am simply not very good at reading and understanding explanations before I begin a task, and it’s this tendency that’s making the game Uncle Chop’s Rocket Shop a bit of a nightmare for me, but also really fun.

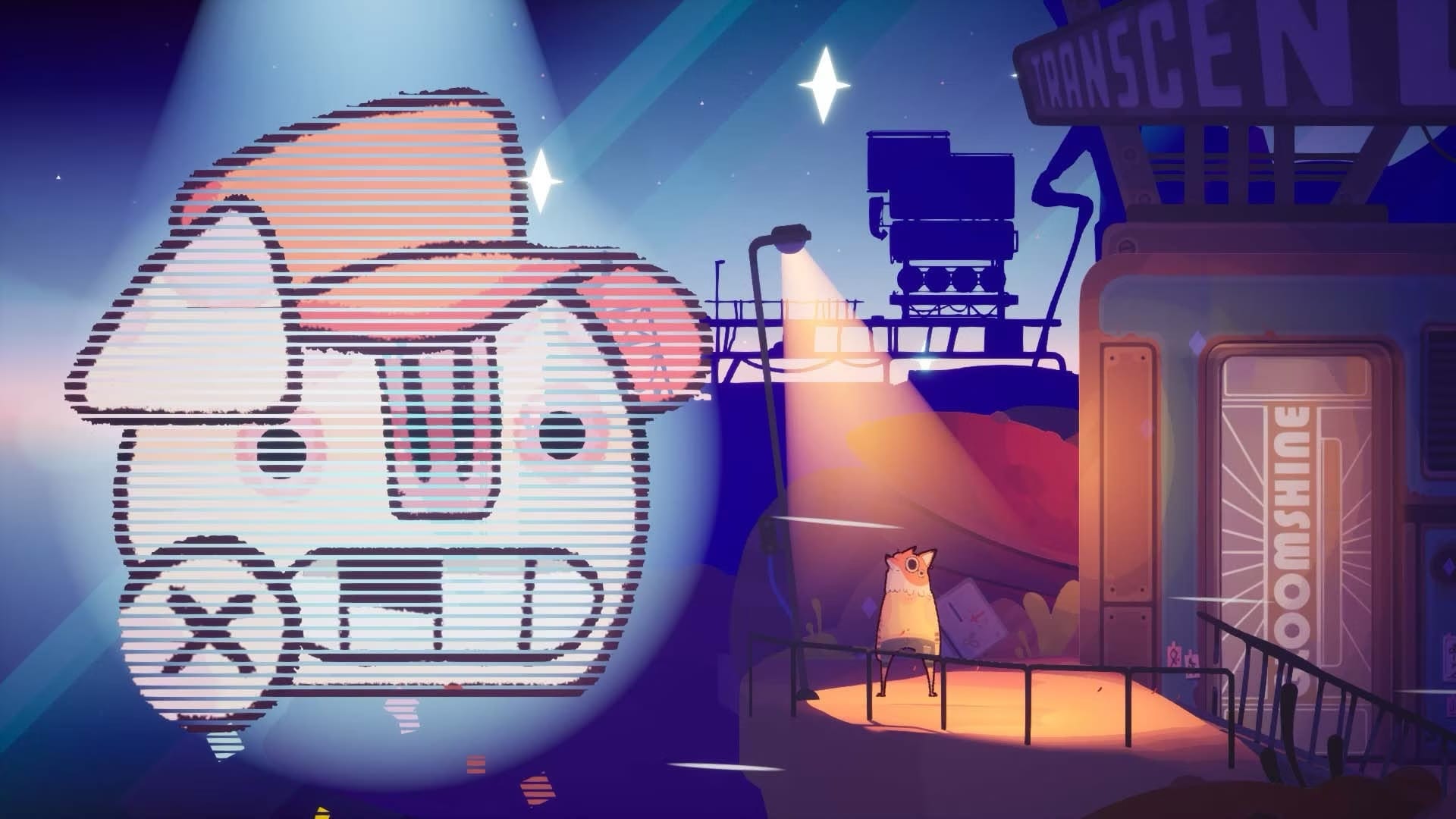

Uncle Chop’s Rocket Shop came out in 2024, and it’s been sitting in my Epic store library for a while before I finally decided to check it out this week. You play as Wilbur, a fox-headed dude who inherits an intergalactic mechanic’s shop and has to fix enough spaceships to make growing rent payments. There’s more plot than this– I’m only a few in-game days in, and I’ve already encountered mystical beings, thieves, meteor showers, and other hints that this isn’t just a job simulator. It’s possible to die, but the game is also a roguelike, with upgrades to your mechanic’s shop persisting between runs. But the bulk of your day is taken up by choosing from a number of repair jobs and getting them done to the customer’s satisfaction.

There are two modes to choose from: one with time pressure, where customers will get angry if you don’t fix their ships fast enough, and one that does away with the clock but makes the repairs harder and more exacting. I hate time pressure in games so opted for this more chill mode. This seems like a good way to learn the game, and especially how to come to grips with its giant, weird manual.

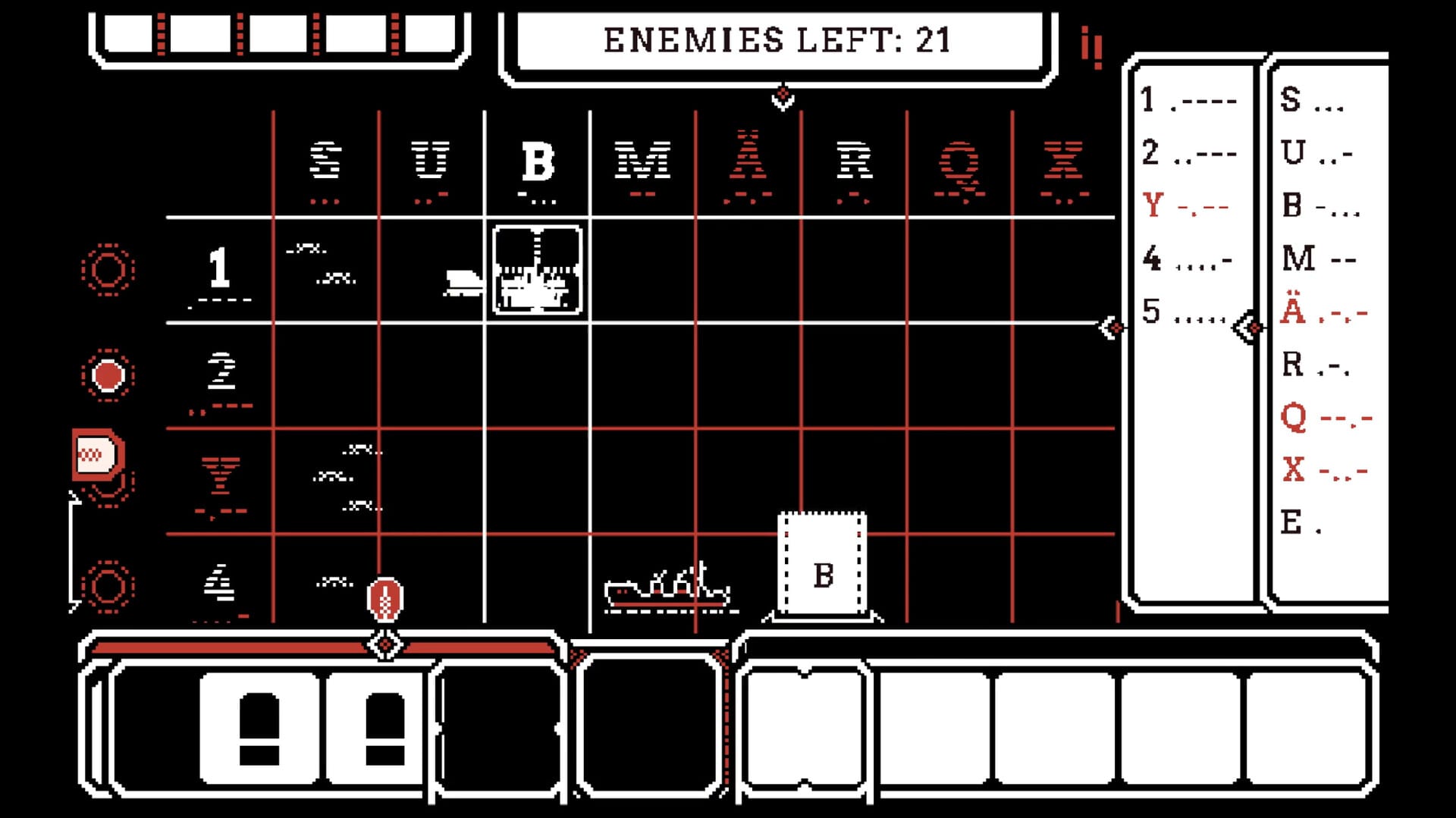

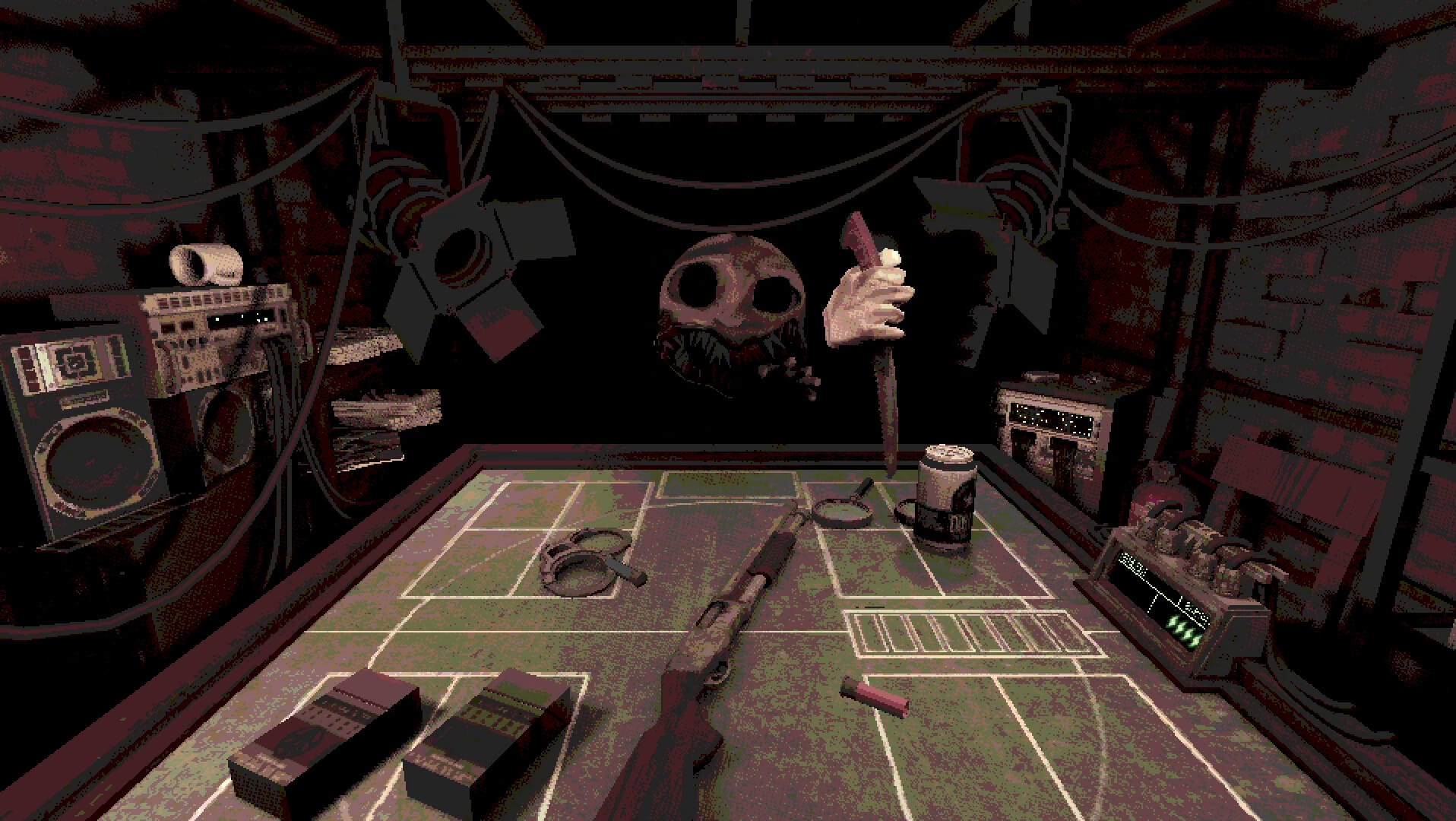

When you go to refill a customer’s fuel pump, for instance, you’ll see a symbol that will tell you which tab in the manual to go to, which you do by physically pulling the book out of your inventory and clicking through its pages. There, you’ll get a variety of images, brisk instructions, and references to other parts of the manual that will help you troubleshoot and solve the problem. My fuel jobs have been pretty basic–remove the fuel cell, refill it at my fuel station without filling it too far and exploding it, putting it back in. Oil is a little more complicated–in addition to the oil levels, there’s the oil quality to consider, as well as a pump, heat gauge, and other gadgets that could be busted. A recent job included both of these tasks and two new complications. There was an alarm that wouldn’t stop timing out and locking me out of the other ship modules, which had to be disarmed with a series of puzzles, and a “tomfoolery” module that required buying a new repair station to fix and then playing a whole other video game to calibrate.

The actual fixing is wonderfully tactile, with lots of buttons to press and levers to pull and bolts to unscrew. Just like in real life, you have to make sure you do all these things–I’ve lost money for forgetting to close a panel back up, or gotten stuck because I was flipping switches in the wrong order. The manual tells you all this, but it’s written like a real professional manual that assumes a certain familiarity with the objects at hand. Everything you need to know is in there, but it can be a little baffling to get your head around, especially if you’re not a great visual learner or are me, who cannot help himself from skimming the instructions before diving into a ship’s guts. In the game’s time-pressure mode, I imagine learning a new task for the first time requires an overwhelming amount of speedreading and making good choices, but in my chill mode I have no justification for not taking the time to look everything over first besides being a dumbass. I find it hard to understand the manual without experiencing the thing it’s describing, but going step-by-step often gets me stumped if a problem is deeper in the book. I’ll plunge ahead with unearned confidence, run into problems, give the manual the most cursory glance, dive back in, and get stumped again, in an absurd loop I have no one to blame for but myself.

I hate reading directions, but I do like research, so I enjoy looking stuff up in the manual even if I’m not fully digesting it. It’s hard not to get impatient to fiddle with all the strange machines, which give me some great Spaceteam vibes. The computer I’m playing Uncle Chop’s on sits next to an Ikea bookshelf I put together myself also without reading the instructions in full, and which is now listing to one side because I didn’t pay enough attention to the importance of rigorously attaching its shitty plywood back. Looking up from a game that reminds me I apparently haven’t grown at all as a person since third grade to real-world proof of the fact that I haven’t grown at all as a person since third grade is a lot, and the in-game consequences for my bad habit feel like a reminder that there will also be real-world consequences when my bookshelf inevitably collapses. At least in the game I’ll get a chance to start again, unlike my bookshelf, which will destroy everything around it when it forces me to pay for my hubris.

Uncle Chop’s Rocket Shop is available on PC and consoles.