MIT researchers identify routes to stronger titanium alloys

Titanium alloys are essential structural materials for a wide variety of applications, from aerospace and energy infrastructure to biomedical equipment. But like most metals, optimizing their properties tends to involve a tradeoff between two key characteristics: strength and ductility. Stronger materials tend to be less deformable, and deformable materials tend to be mechanically weak.

Now, researchers at MIT, collaborating with researchers at ATI Specialty Materials, have discovered an approach for creating new titanium alloys that can exceed this historical tradeoff, leading to new alloys with exceptional combinations of strength and ductility, which might lead to new applications.

The findings are described in the journal Advanced Materials, in a paper by Shaolou Wei ScD ’22, Professor C. Cem Tasan, postdoc Kyung-Shik Kim, and John Foltz from ATI Inc. The improvements, the team says, arise from tailoring the chemical composition and the lattice structure of the alloy, while also adjusting the processing techniques used to produce the material at industrial scale.

Titanium alloys have been important because of their exceptional mechanical properties, corrosion resistance, and light weight when compared to steels for example. Through careful selection of the alloying elements and their relative proportions, and of the way the material is processed, “you can create various different structures, and this creates a big playground for you to get good property combinations, both for cryogenic and elevated temperatures,” Tasan says.

But that big assortment of possibilities in turn requires a way to guide the selections to produce a material that meets the specific needs of a particular application. The analysis and experimental results described in the new study provide that guidance.

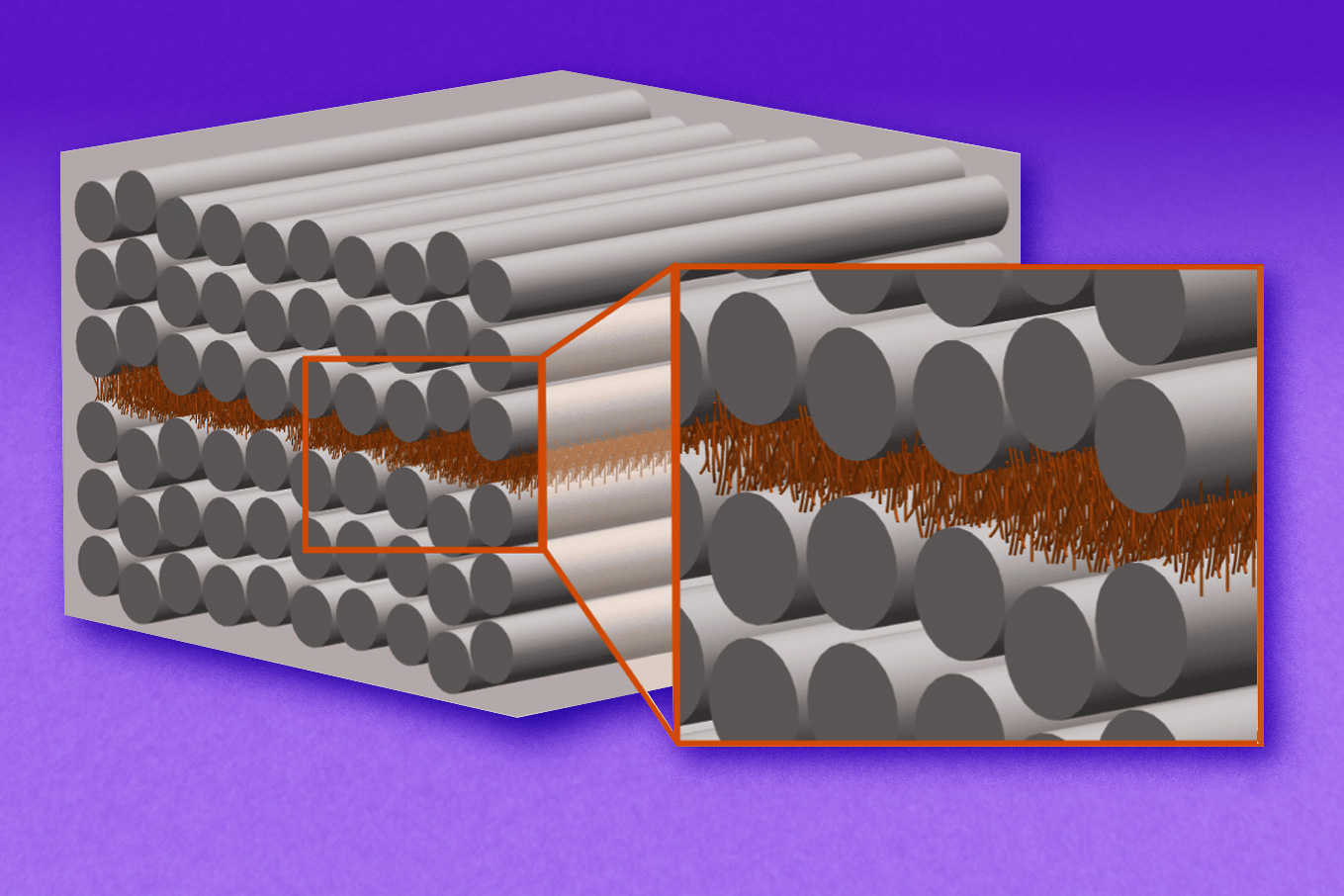

The structure of titanium alloys, all the way down to atomic scale, governs their properties, Tasan explains. And in some titanium alloys, this structure is even more complex, made up of two different intermixed phases, known as the alpha and beta phases.

“The key strategy in this design approach is to take considerations of different scales,” he says. “One scale is the structure of individual crystal. For example, by choosing the alloying elements carefully, you can have a more ideal crystal structure of the alpha phase that enables particular deformation mechanisms. The other scale is the polycrystal scale, that involves interactions of the alpha and beta phases. So, the approach that’s followed here involves design considerations for both.”

In addition to choosing the right alloying materials and proportions, steps in the processing turned out to play an important role. A technique called cross-rolling is another key to achieving the exceptional combination of strength and ductility, the team found.

Working together with ATI researchers, the team tested a variety of alloys under a scanning electron microscope as they were being deformed, revealing details of how their microstructures respond to external mechanical load. They found that there was a particular set of parameters — of composition, proportions, and processing method — that yielded a structure where the alpha and beta phases shared the deformation uniformly, mitigating the cracking tendency that is likely to occur between the phases when they respond differently. “The phases deform in harmony,” Tasan says. This cooperative response to deformation can yield a superior material, they found.

“We looked at the structure of the material to understand these two phases and their morphologies, and we looked at their chemistries by carrying out local chemical analysis at the atomic scale. We adopted a wide variety of techniques to quantify various properties of the material across multiple length scales, says Tasan, who is the POSCO Professor of Materials Science and Engineering and an associate professor of metallurgy. “When we look at the overall properties” of the titanium alloys produced according to their system, “the properties are really much better than comparable alloys.”

This was industry-supported academic research aimed at proving design principles for alloys that can be commercially produced at scale, according to Tasan. “What we do in this collaboration is really toward a fundamental understanding of crystal plasticity,” he says. “We show that this design strategy is validated, and we show scientifically how it works,” he adds, noting that there remains significant room for further improvement.

As for potential applications of these findings, he says, “for any aerospace application where an improved combination of strength and ductility are useful, this kind of invention is providing new opportunities.”

The work was supported by ATI Specialty Rolled Products and used facilities of MIT.nano and the Center for Nanoscale Systems at Harvard University.

© Image: iStock