3 Questions: Darrell Irvine on making HIV vaccines more powerful

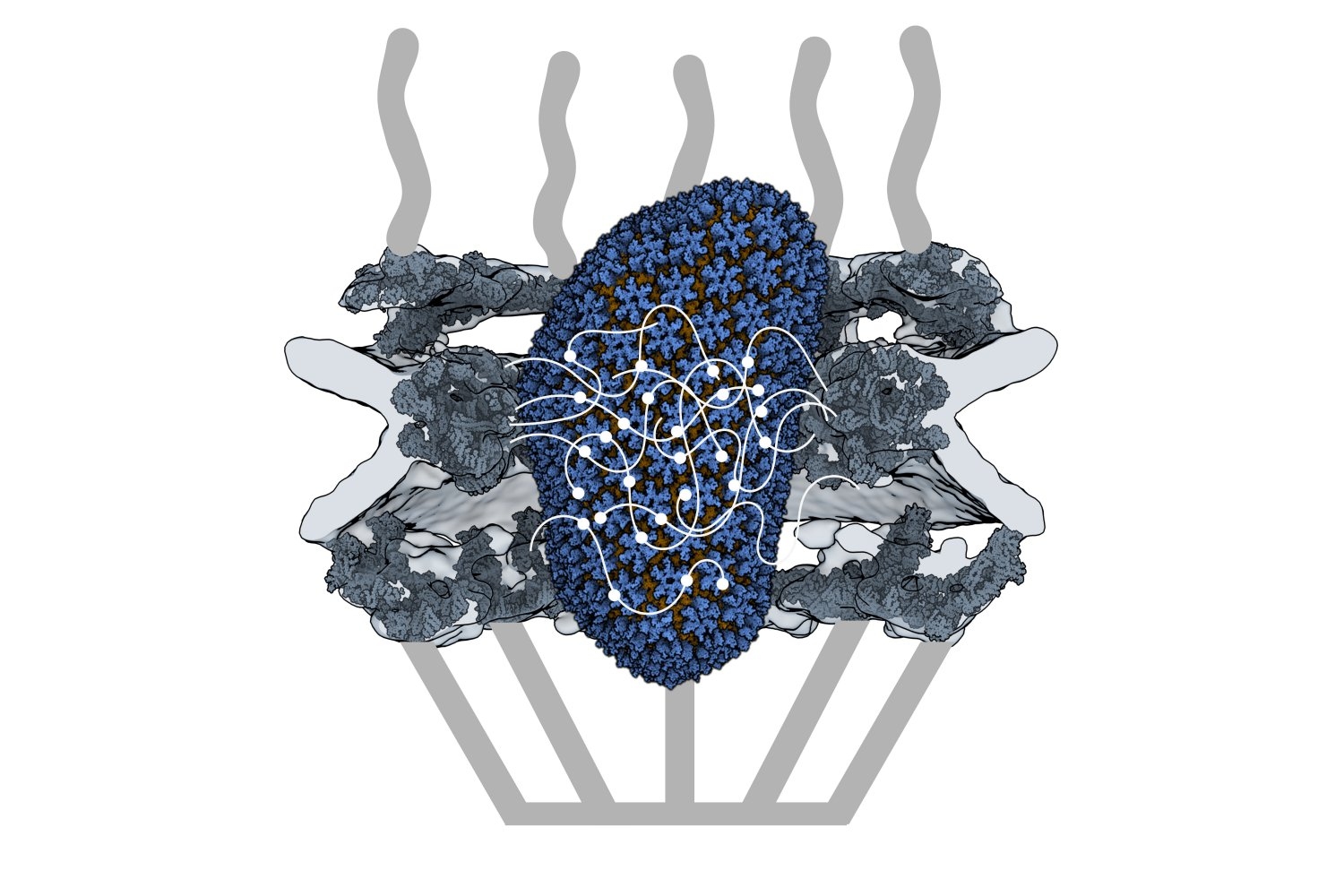

An MIT research team led by Professor Darrell Irvine has developed a novel kind of vaccine adjuvant: a nanoparticle that can help to stimulate the immune system to generate a stronger response to a vaccine. These nanoparticles contain saponin, a compound derived from the bark of the Chilean soapbark tree, along with a molecule called MPLA, each of which helps to activate the immune system.

The adjuvant has been incorporated into an experimental HIV vaccine that has shown promising results in animal studies, and this month, the first human volunteers will receive the vaccine as part of a phase 1 clinical trial run by the Consortium for HIV/AIDS Vaccine Development at the Scripps Research Institute. MIT News spoke with Irvine about why this project required an interdisciplinary approach, and what may lie ahead.

Q: What are the special features of the new nanoparticle adjuvant that help it create a more powerful immune response to vaccination?

A: Most vaccines, such as the Covid-19 vaccines, are thought to protect us through B cells making protective antibodies. Development of an HIV vaccine has been made challenging by the fact that the B cells that are capable of evolving to produce protective antibodies — called broadly neutralizing antibodies — are very rare in the average person. Vaccine adjuvants are important in this scenario to ensure that when we immunize with an HIV antigen, these rare B cells become activated and get a chance to participate in the immune response.

We particularly discovered that this new adjuvant, which we call SMNP (short for saponin/MPLA nanoparticles), is particularly good at helping more B cells enter germinal centers, the specialized location in lymph nodes where high affinity antibodies are produced. In animal models, SMNP also has shown unique mechanisms of action: Administering antigens with SMNP leads to better antigen delivery to lymph nodes (through increases in lymph flow) and better capture of the antigen by B cells in lymph nodes.

Q: How did your lab, which generally focuses on bioengineering and materials science, end up working on HIV vaccines? What obstacles did you have to overcome in the development of this adjuvant?

A: About 15 years ago, Bruce Walker approached me about getting involved in the HIV vaccine effort, and recruited me to join the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard as a member of the steering committee. Through the Ragon Institute, I met colleagues in the Scripps Consortium for HIV/AIDS Vaccine Development (CHAVD), and we realized there was a tremendous opportunity to directly contribute to the HIV vaccine challenge, working in partnership with experts in immunogen design, structural biology, and HIV pathogenesis.

As we carried out study after study of SMNP in preclinical animal models, we realized the adjuvant had really amazing effects for promoting anti-HIV antibody responses, and the CHAVD decided this was worth moving forward to testing in humans. A major challenge was transferring the technology out of the lab to synthesize large amounts of the adjuvant under GMP (good manufacturing process) conditions for a clinical trial. The initial contract manufacturing organization (CMO) hired by the consortium to produce SMNP simply couldn’t get a process to work for scalable manufacturing.

Luckily for us, a chemical engineering graduate student, Ivan Pires, whom I co-advise with Paula Hammond, head of MIT’s Department of Chemical Engineering, had developed expertise in one particular processing technique known as tangential flow filtration during his undergraduate training. Leveraging classic chemical engineering skills in thermodynamics and process design, Ivan stepped in and solved the process issues the CMO was facing, allowing the manufacturing to move forward. This to me is what makes MIT great — the ability of our students and postdocs to step up and solve big problems and make big contributions when the need arises.

Q: What other diseases could this approach be useful for? Are there any plans to test it with other types of vaccines?

A: In principle, SMNP may be helpful for any infectious disease vaccine where strong antibody responses are needed. We are currently sharing the adjuvant with about 30 different labs around the world, who are testing it in vaccines against many other pathogens including Epstein-Barr virus, malaria, and influenza. We are hopeful that if SMNP is safe and effective in humans, this will be an adjuvant that can be broadly used in infectious disease trials.

© Photo: Steve Boxall