Professor Emeritus John Vander Sande, microscopist, entrepreneur, and admired mentor, dies at 80

MIT Professor Emeritus John B. Vander Sande, a pioneer in electron microscopy and beloved educator and advisor known for his warmth and empathetic instruction, died June 28 in Newbury, Massachusetts. He was 80.

The Cecil and Ida Green Distinguished Professor in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering (DMSE), Vander Sande was a physical metallurgist, studying the physical properties and structure of metals and alloys. His long career included a major entrepreneurial pursuit, launching American Superconductor; forming international academic partnerships; and serving in numerous administrative roles at MIT and, after his retirement, one in Iceland.

Vander Sande’s interests encompassed more than science and technology; a self-taught scholar on 17th- and 18th-century furniture, he boasts a production credit in the 1996 film “The Crucible.”

He is perhaps best remembered for bringing the first scanning transmission electron microscope (STEM) into the United States. This powerful microscope uses a beam of electrons to scan material samples and investigate their structure and composition.

“John was the person who really built up what became MIT’s modern microscopy expertise,” says Samuel M. Allen, the POSCO Professor Emeritus of Physical Metallurgy. Vander Sande studied electron microscopy during a postdoctoral fellowship at Oxford University in England with luminaries Sir Peter Hirsch and Colin Humphreys. “The people who wrote the first book on transmission electron microscopy were all there at Oxford, and John basically brought that expertise to MIT in his teaching and mentoring.”

Born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1944, Vander Sande grew up in Westwood, New Jersey. He studied mechanical engineering at Stevens Institute of Technology, earning a bachelor’s degree in 1966, and switched to materials science and engineering at Northwestern University, receiving a PhD in 1970. Following his time at Oxford, Vander Sande joined MIT as assistant professor in 1971.

A vision for advanced microscopy

At MIT, Vander Sande became known as a leading practitioner of weak-beam microscopy, a technique refined by Hirsch to improve images of dislocations, tiny imperfections in crystalline materials that help researchers determine why materials fail.

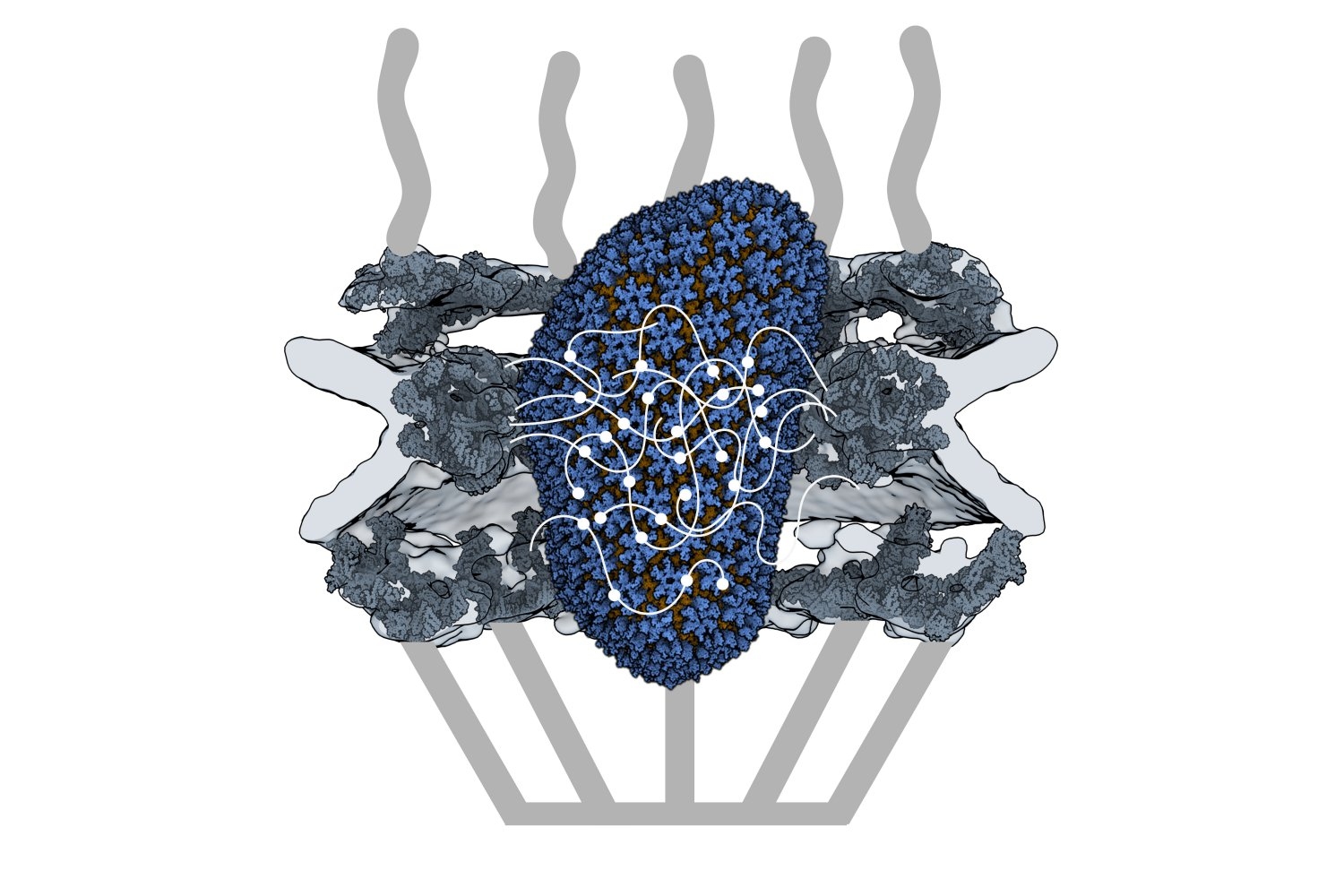

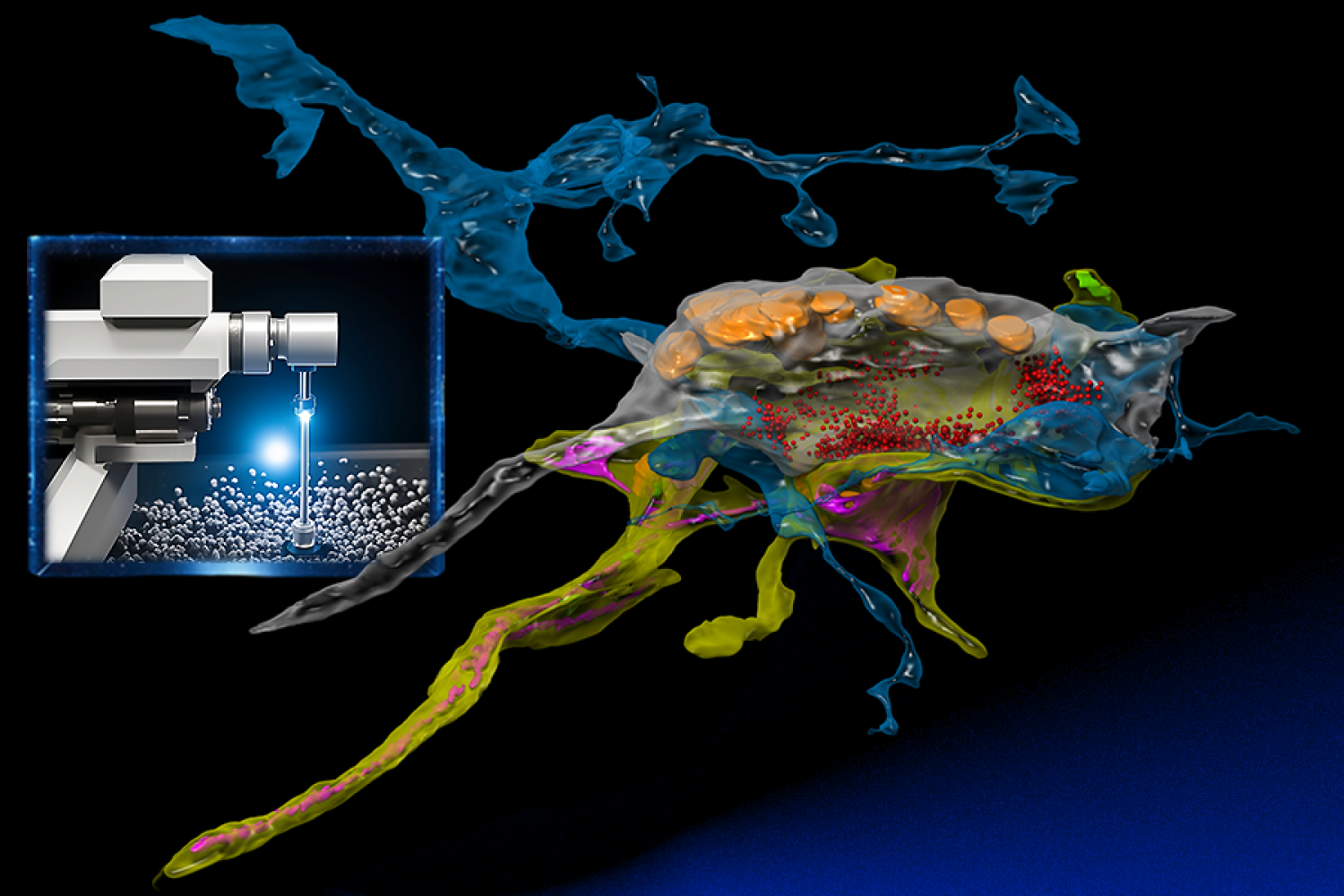

His procurement of the STEM instrument from the U.K. company Vacuum Generators in the mid-1970s was a substantial innovation, allowing researchers to visualize individual atoms and identify chemical elements in materials.

“He showed the capabilities of new techniques, like scanning transmission electron microscopy, in understanding the physics and chemistry of materials at the nanoscale,” says Yet-Ming Chiang, the Kyocera Professor of Ceramics at DMSE. Today, MIT.nano stands as one of the world’s foremost facilities for advanced microscopy techniques. “He paved the way, at MIT, certainly, and more broadly, to those state-of-the-art instruments that we have today.”

The director of a microscopy laboratory at MIT, Vander Sande used instruments like that early STEM and its successors to study how manufacturing processes affect material structure and properties.

One focus was rapid solidification, which involves cooling materials quickly to enhance their properties. Tom Kelly, a PhD student in the late 1970s, worked with Vander Sande to explore how fast-cooling molten metal as powder changes its internal structure. They discovered that “precipitates,” or small particles formed during the rapid cooling, made the metal stronger.

“It took me at least a year to finally get some success. But we did succeed,” says Kelly, CEO of STEAM Instruments, a startup that is developing mass spectrometry technology, which measures and analyzes atoms emitted by substances. “That was John who brought that project and the solution to the table.”

Using his deep expertise in metals and other materials, including superconducting oxides, which can conduct electricity when cooled to low temperatures, Vander Sande co-founded American Superconductor with fellow DMSE faculty member Greg Yurek in 1987. The company produced high-temperature superconducting wires now used in renewable energy technology.

“In the MIT entrepreneurial ecosystem, American Superconductor was a pioneer,” says Chiang, who was part of the startup’s co-founding membership. “It was one of the early companies that was formed on the basis of research at MIT, in which faculty spun out a company, as opposed to graduates starting companies.”

To teach them is to know them

While Yurek left MIT to lead the American Superconductor full time as CEO, Vander Sande stayed on the faculty at DMSE, remaining a consultant to the company and board member for many years.

That comes as no surprise to his students, who recall a passionate and devoted educator and mentor.

“He was a terrific teacher,” says Frank Gayle, a former PhD student of Vander Sande’s who recently retired from his job as director at the National Institute of Standards and Technology. “He would take the really complex subjects, super mathematical and complicated, and he would teach them in a way that you felt comfortable as a student learning them. He really had a terrific knack for that.”

Chiang said Vander Sande was an “exceptionally clear” lecturer who would use memorable imagery to get concepts across, like comparing heterogenous nanoparticles, tiny particles that have a varied structure or composition, to a black-and-white Holstein cow. “Hard to forget,” Chiang says.

Powering Vander Sande’s teaching, Gayle said, was an aptitude for knowing the people he was teaching, for recognizing their backgrounds and what they knew and didn’t know. He likened Vander Sande to a dad on Take Your Kid to Work Day, demystifying an unfamiliar world. “He had some way of doing that, and then he figured out how to get the pieces together to make it comprehensible.”

He brought a similar talent to mentorship, with an emphasis on the individual rather than the project, Gayle says. “He really worked with people to encourage them to do creative things and encouraged their creativity.”

Kelly, who was a University of Wisconsin professor before becoming a repeat entrepreneur, says Vander Sande was an exceptional role model for young grad students.

“When you see these people who’ve accomplished a lot, you’re afraid to even talk to them,” he says. “But in reality, they’re regular people. One of the things I learned from John was that he’s just a regular person who does good work. I realized that, Hey, I can be a regular person and do good work, too.”

Another former grad student, Matt Libera, says he learned as much about life from Vander Sande as he did about materials science and engineering.

“Because he was not just a scientist-engineer, but really a well-rounded human being and shared a lot of experience and advice that went beyond just the science,” says Libera, a materials science and engineering professor at Stevens Institute of Technology, Vander Sande’s alma mater.

“A rare talent”

Vander Sande was equally dedicated to MIT and his department. In DMSE, he was on multiple committees, on undergraduates and curriculum development, and in 1991 he was appointed associate dean of the School of Engineering. He served in the position until 1999, taking over as acting dean twice.

“I remember that that took up a huge amount of his time,” Chiang says. Vander Sande lived in Newbury, Massachusetts, and he and his wife, Marie-Teresa, who long worked for MIT’s Industrial Liaison Program, would travel together to Cambridge by car. “He once told me that he did a lot of the work related to his deanship during that long commute back and forth from Newbury.”

Gayle says Vander Sande’s remarkable communication and people skills are what made him a good fit for leadership roles. “He had a rare talent for those things.”

He also was a bridge from MIT to the rest of the world. Vander Sande played a leading role in establishing the Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology, a teaching partnership that set up Institute-modeled graduate programs at Singaporean universities. And he was the director of MIT’s half of the Cambridge-MIT Institute, a collaboration with the University of Cambridge in the U.K. that focused on student and faculty exchanges, integrated research, and professional development. Retiring from MIT in 2006, he pursued academic projects in Ecuador, Morocco, and Iceland, and served as acting provost of Reykjavik University from 2009 to 2010.

He had numerous interests outside work, including college football and sports cars, but his greatest passion was for antiques, mainly early American furniture.

A self-taught expert in antiquarian arts, he gave lectures on connoisseurship and attended auctions and antique shows. His interest extended to his home, built in 1697, which had low ceilings that were inconvenient for the 6-foot-1 Vander Sande.

So respected was he for his expertise that the production crew for 20th Century Fox’s “The Crucible” sought him out. The film, about the Salem, Massachusetts, witch trials, was set in 1692. The crew made copies of furniture from his collection, and Vander Sande consulted on set design and decoration to ensure historical accuracy.

His passion extended beyond just historical artifacts, says Professor Emeritus Allen. He was profoundly interested in learning about the people behind them.

“He liked to read firsthand accounts, letters and stuff,” he says. “His real interest was trying to understand how people two centuries ago or more thought, what their lives were like. It wasn’t just that he was an antiques collector.”

Vander Sande is survived by his wife, Marie-Teresa Vander Sande; his son, John Franklin VanderSande, and his wife, Melanie; his daughter, Rosse Marais VanderSande Ellis, and her husband, Zak Ellis; and grandchildren Gabriel Rhys Pelletier, Sophia Marais VanderSande, and John Christian VanderSande.

© Photo courtesy of the DMSE.