More durable metals for fusion power reactors

For many decades, nuclear fusion power has been viewed as the ultimate energy source. A fusion power plant could generate carbon-free energy at a scale needed to address climate change. And it could be fueled by deuterium recovered from an essentially endless source — seawater.

Decades of work and billions of dollars in research funding have yielded many advances, but challenges remain. To Ju Li, the TEPCO Professor in Nuclear Science and Engineering and a professor of materials science and engineering at MIT, there are still two big challenges. The first is to build a fusion power plant that generates more energy than is put into it; in other words, it produces a net output of power. Researchers worldwide are making progress toward meeting that goal.

The second challenge that Li cites sounds straightforward: “How do we get the heat out?” But understanding the problem and finding a solution are both far from obvious.

Research in the MIT Energy Initiative (MITEI) includes development and testing of advanced materials that may help address those challenges, as well as many other challenges of the energy transition. MITEI has multiple corporate members that have been supporting MIT’s efforts to advance technologies required to harness fusion energy.

The problem: An abundance of helium, a destructive force

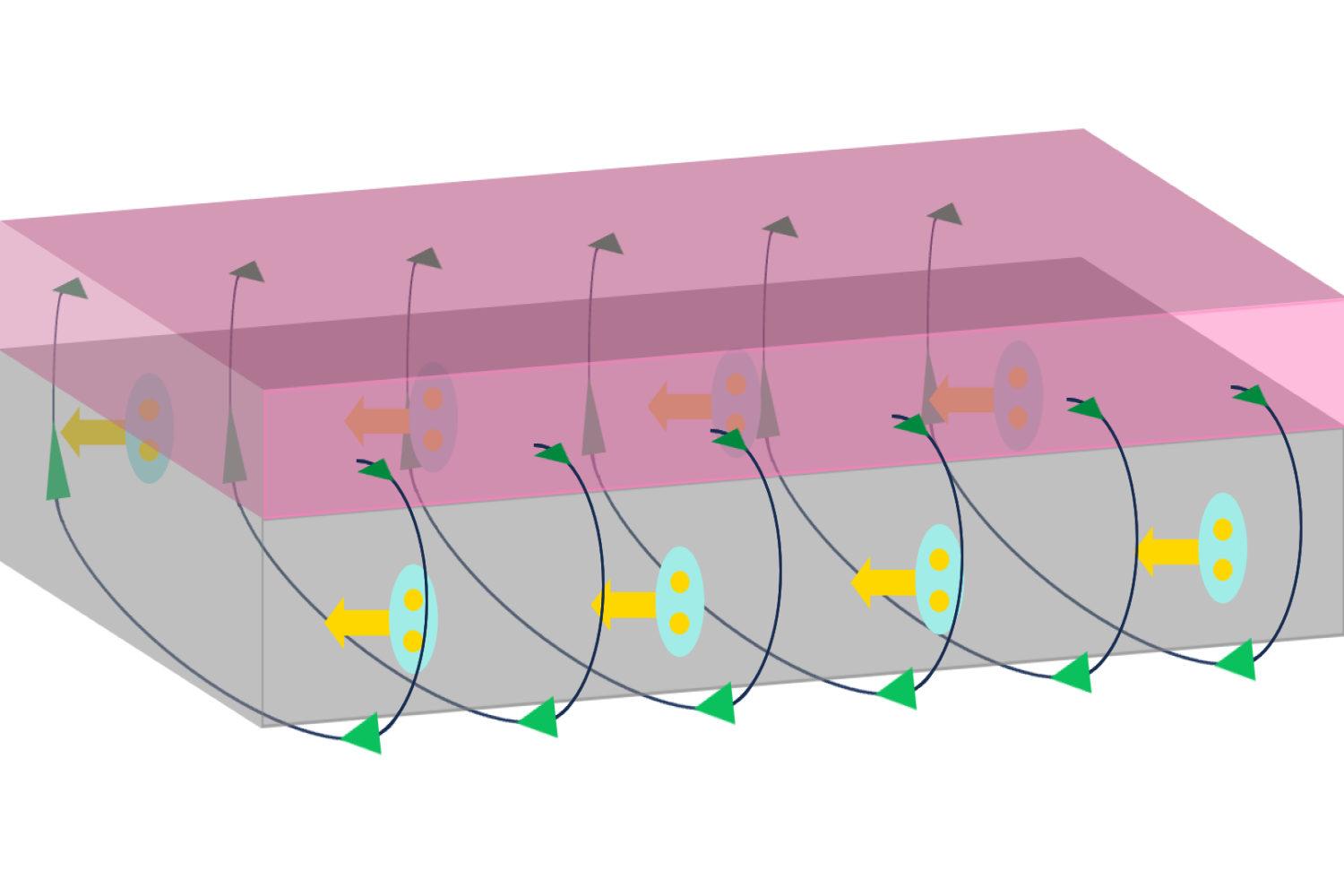

Key to a fusion reactor is a superheated plasma — an ionized gas — that’s reacting inside a vacuum vessel. As light atoms in the plasma combine to form heavier ones, they release fast neutrons with high kinetic energy that shoot through the surrounding vacuum vessel into a coolant. During this process, those fast neutrons gradually lose their energy by causing radiation damage and generating heat. The heat that’s transferred to the coolant is eventually used to raise steam that drives an electricity-generating turbine.

The problem is finding a material for the vacuum vessel that remains strong enough to keep the reacting plasma and the coolant apart, while allowing the fast neutrons to pass through to the coolant. If one considers only the damage due to neutrons knocking atoms out of position in the metal structure, the vacuum vessel should last a full decade. However, depending on what materials are used in the fabrication of the vacuum vessel, some projections indicate that the vacuum vessel will last only six to 12 months. Why is that? Today’s nuclear fission reactors also generate neutrons, and those reactors last far longer than a year.

The difference is that fusion neutrons possess much higher kinetic energy than fission neutrons do, and as they penetrate the vacuum vessel walls, some of them interact with the nuclei of atoms in the structural material, giving off particles that rapidly turn into helium atoms. The result is hundreds of times more helium atoms than are present in a fission reactor. Those helium atoms look for somewhere to land — a place with low “embedding energy,” a measure that indicates how much energy it takes for a helium atom to be absorbed. As Li explains, “The helium atoms like to go to places with low helium embedding energy.” And in the metals used in fusion vacuum vessels, there are places with relatively low helium embedding energy — namely, naturally occurring openings called grain boundaries.

Metals are made up of individual grains inside which atoms are lined up in an orderly fashion. Where the grains come together there are gaps where the atoms don’t line up as well. That open space has relatively low helium embedding energy, so the helium atoms congregate there. Worse still, helium atoms have a repellent interaction with other atoms, so the helium atoms basically push open the grain boundary. Over time, the opening grows into a continuous crack, and the vacuum vessel breaks.

That congregation of helium atoms explains why the structure fails much sooner than expected based just on the number of helium atoms that are present. Li offers an analogy to illustrate. “Babylon is a city of a million people. But the claim is that 100 bad persons can destroy the whole city — if all those bad persons work at the city hall.” The solution? Give those bad persons other, more attractive places to go, ideally in their own villages.

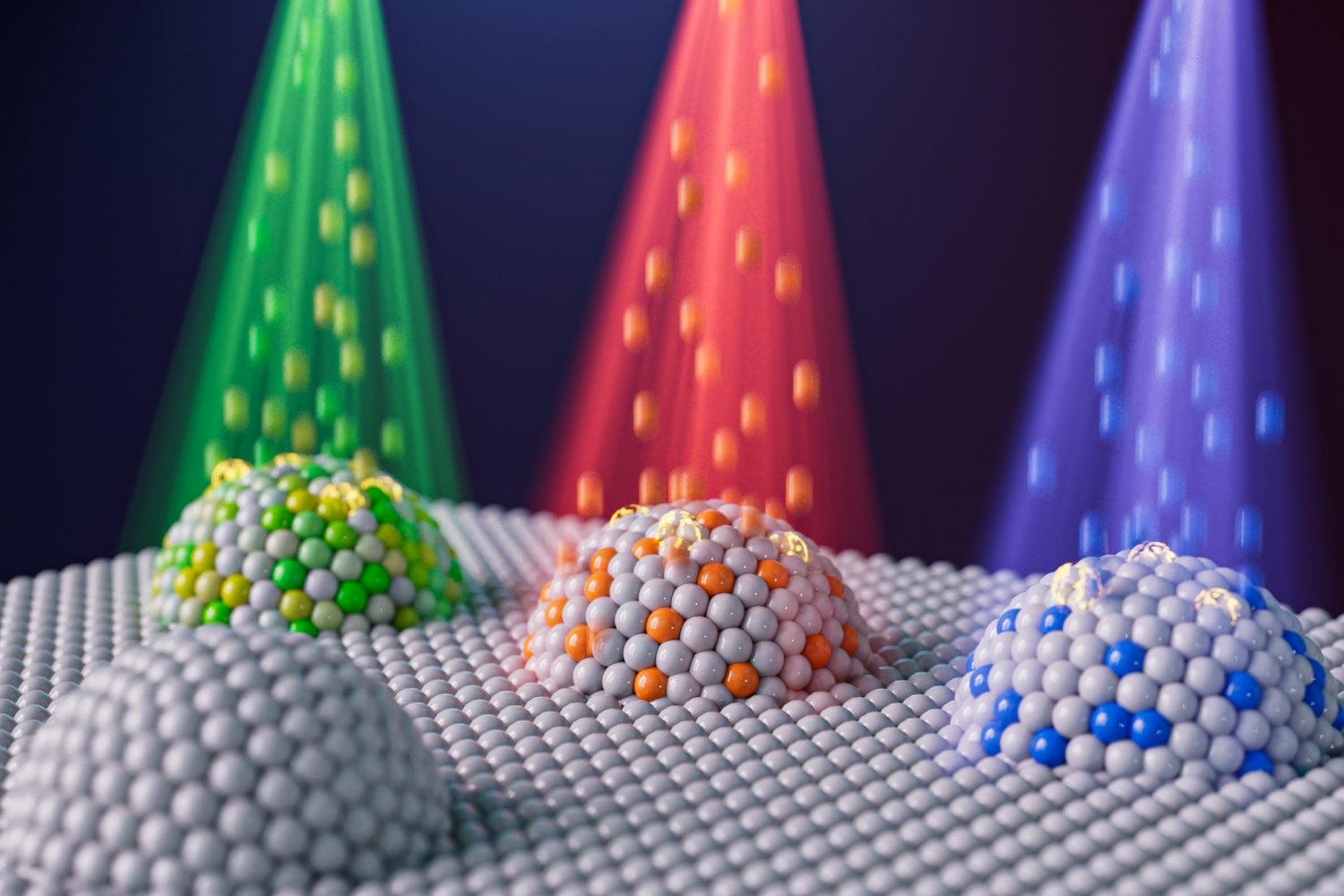

To Li, the problem and possible solution are the same in a fusion reactor. If many helium atoms go to the grain boundary at once, they can destroy the metal wall. The solution? Add a small amount of a material that has a helium embedding energy even lower than that of the grain boundary. And over the past two years, Li and his team have demonstrated — both theoretically and experimentally — that their diversionary tactic works. By adding nanoscale particles of a carefully selected second material to the metal wall, they’ve found they can keep the helium atoms that form from congregating in the structurally vulnerable grain boundaries in the metal.

Looking for helium-absorbing compounds

To test their idea, So Yeon Kim ScD ’23 of the Department of Materials Science and Engineering and Haowei Xu PhD ’23 of the Department of Nuclear Science and Engineering acquired a sample composed of two materials, or “phases,” one with a lower helium embedding energy than the other. They and their collaborators then implanted helium ions into the sample at a temperature similar to that in a fusion reactor and watched as bubbles of helium formed. Transmission electron microscope images confirmed that the helium bubbles occurred predominantly in the phase with the lower helium embedding energy. As Li notes, “All the damage is in that phase — evidence that it protected the phase with the higher embedding energy.”

Having confirmed their approach, the researchers were ready to search for helium-absorbing compounds that would work well with iron, which is often the principal metal in vacuum vessel walls. “But calculating helium embedding energy for all sorts of different materials would be computationally demanding and expensive,” says Kim. “We wanted to find a metric that is easy to compute and a reliable indicator of helium embedding energy.”

They found such a metric: the “atomic-scale free volume,” which is basically the maximum size of the internal vacant space available for helium atoms to potentially settle. “This is just the radius of the largest sphere that can fit into a given crystal structure,” explains Kim. “It is a simple calculation.” Examination of a series of possible helium-absorbing ceramic materials confirmed that atomic free volume correlates well with helium embedding energy. Moreover, many of the ceramics they investigated have higher free volume, thus lower embedding energy, than the grain boundaries do.

However, in order to identify options for the nuclear fusion application, the screening needed to include some other factors. For example, in addition to the atomic free volume, a good second phase must be mechanically robust (able to sustain a load); it must not get very radioactive with neutron exposure; and it must be compatible — but not too cozy — with the surrounding metal, so it disperses well but does not dissolve into the metal. “We want to disperse the ceramic phase uniformly in the bulk metal to ensure that all grain boundary regions are close to the dispersed ceramic phase so it can provide protection to those regions,” says Li. “The two phases need to coexist, so the ceramic won’t either clump together or totally dissolve in the iron.”

Using their analytical tools, Kim and Xu examined about 50,000 compounds and identified 750 potential candidates. Of those, a good option for inclusion in a vacuum vessel wall made mainly of iron was iron silicate.

Experimental testing

The researchers were ready to examine samples in the lab. To make the composite material for proof-of-concept demonstrations, Kim and collaborators dispersed nanoscale particles of iron silicate into iron and implanted helium into that composite material. She took X-ray diffraction (XRD) images before and after implanting the helium and also computed the XRD patterns. The ratio between the implanted helium and the dispersed iron silicate was carefully controlled to allow a direct comparison between the experimental and computed XRD patterns. The measured XRD intensity changed with the helium implantation exactly as the calculations had predicted. “That agreement confirms that atomic helium is being stored within the bulk lattice of the iron silicate,” says Kim.

To follow up, Kim directly counted the number of helium bubbles in the composite. In iron samples without the iron silicate added, grain boundaries were flanked by many helium bubbles. In contrast, in the iron samples with the iron silicate ceramic phase added, helium bubbles were spread throughout the material, with many fewer occurring along the grain boundaries. Thus, the iron silicate had provided sites with low helium-embedding energy that lured the helium atoms away from the grain boundaries, protecting those vulnerable openings and preventing cracks from opening up and causing the vacuum vessel to fail catastrophically.

The researchers conclude that adding just 1 percent (by volume) of iron silicate to the iron walls of the vacuum vessel will cut the number of helium bubbles in half and also reduce their diameter by 20 percent — “and having a lot of small bubbles is OK if they’re not in the grain boundaries,” explains Li.

Next steps

Thus far, Li and his team have gone from computational studies of the problem and a possible solution to experimental demonstrations that confirm their approach. And they’re well on their way to commercial fabrication of components. “We’ve made powders that are compatible with existing commercial 3D printers and are preloaded with helium-absorbing ceramics,” says Li. The helium-absorbing nanoparticles are well dispersed and should provide sufficient helium uptake to protect the vulnerable grain boundaries in the structural metals of the vessel walls. While Li confirms that there’s more scientific and engineering work to be done, he, along with Alexander O'Brien PhD ’23 of the Department of Nuclear Science and Engineering and Kang Pyo So, a former postdoc in the same department, have already developed a startup company that’s ready to 3D print structural materials that can meet all the challenges faced by the vacuum vessel inside a fusion reactor.

This research was supported by Eni S.p.A. through the MIT Energy Initiative. Additional support was provided by a Kwajeong Scholarship; the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Laboratory Directed Research and Development program at Idaho National Laboratory; U.S. DOE Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory; and Creative Materials Discovery Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea.

© Photo: Gretchen Ertl