MIT-led team receives funding to pursue new treatments for metabolic disease

A team of MIT researchers will lead a $65.67 million effort, awarded by the U.S. Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H), to develop ingestible devices that may one day be used to treat diabetes, obesity, and other conditions through oral delivery of mRNA. Such devices could potentially be deployed for needle-free delivery of mRNA vaccines as well.

The five-year project also aims to develop electroceuticals, a new form of ingestible therapies based on electrical stimulation of the body’s own hormones and neural signaling. If successful, this approach could lead to new treatments for a variety of metabolic disorders.

“We know that the oral route is generally the preferred route of administration for both patients and health care providers,” says Giovanni Traverso, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at MIT and a gastroenterologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. “Our primary focus is on disorders of metabolism because they affect a lot of people, but the platforms we’re developing could be applied very broadly.”

Traverso is the principal investigator for the project, which also includes Robert Langer, MIT Institute Professor, and Anantha Chandrakasan, dean of the MIT School of Engineering and the Vannevar Bush Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. As part of the project, the MIT team will collaborate with investigators from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, New York University, and the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Over the past several years, Traverso’s and Langer’s labs have designed many types of ingestible devices that can deliver drugs to the GI tract. This approach could be especially useful for protein drugs and nucleic acids, which typically can’t be given orally because they break down in the acidic environment of the digestive tract.

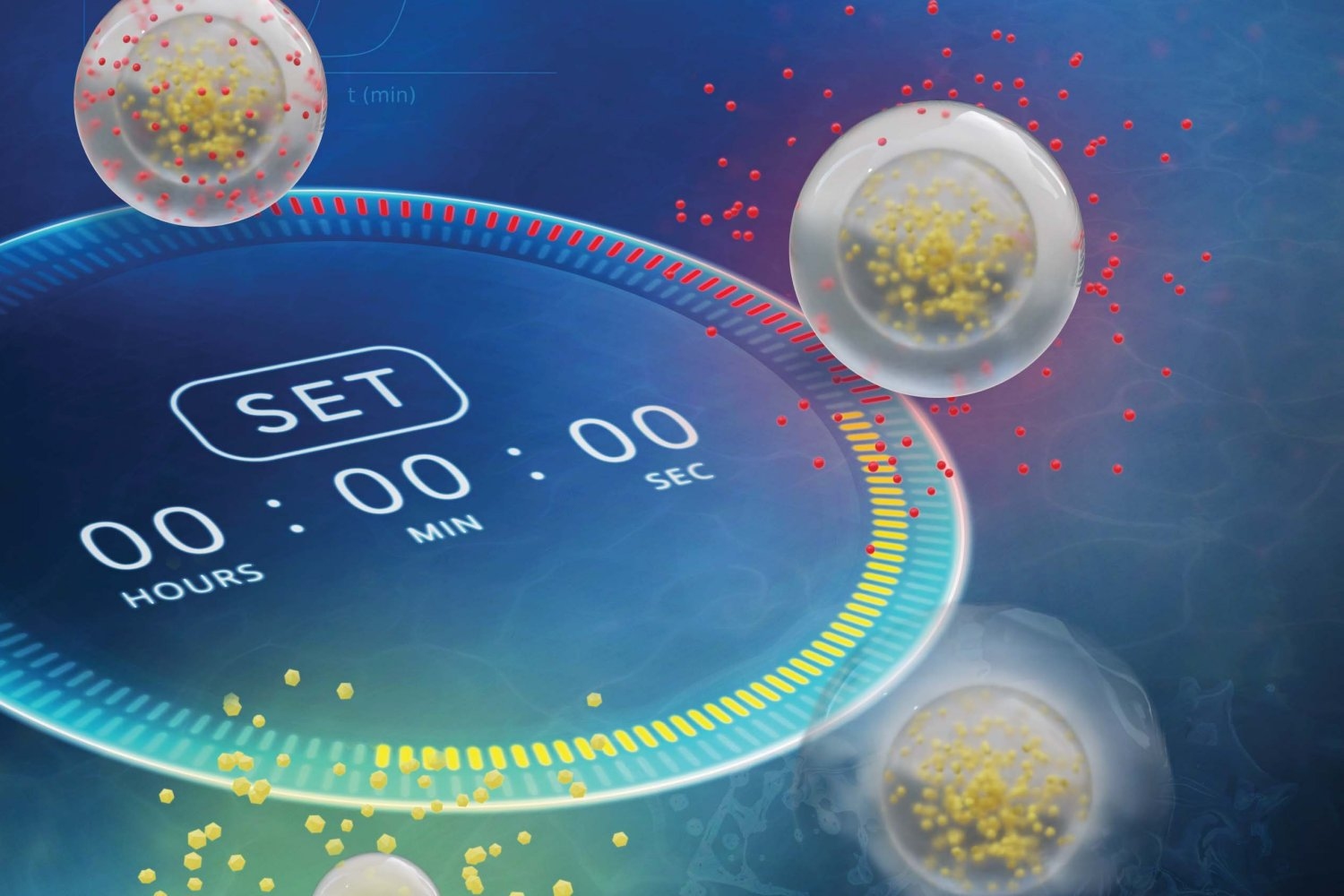

Messenger RNA has already proven useful as a vaccine, directing cells to produce fragments of viral proteins that trigger an immune response. Delivering mRNA to cells also holds potential to stimulate production of therapeutic molecules to treat a variety of diseases. In this project, the researchers plan to focus on metabolic diseases such as diabetes.

“What mRNA can do is enable the potential for dosing therapies that are very difficult to dose today, or provide longer-term coverage by essentially creating an internal factory that produces a therapy for a prolonged period,” Traverso says.

In the mRNA portion of the project, the research team intends to identify lipid and polymer nanoparticle formulations that can most effectively deliver mRNA to cells, using machine learning to help identify the best candidates. They will also develop and test ingestible devices to carry the mRNA-nanoparticle payload, with the goal of running a clinical trial in the final year of the five-year project.

The work will build on research that Traverso’s lab has already begun. In 2022, Traverso and his colleagues reported that they could deliver mRNA in capsules that inject mRNA-nanoparticle complexes into the lining of the stomach.

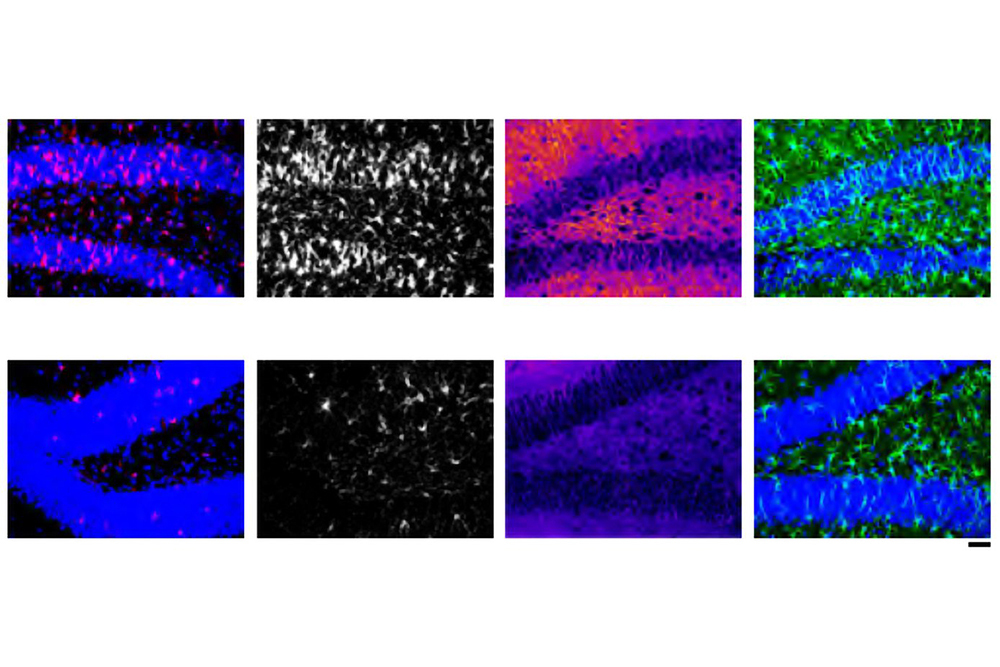

The other branch of the project will focus on ingestible devices that can deliver a small electrical current to the lining of the stomach. In a study published last year, Traverso’s lab demonstrated this approach for the first time, using a capsule coated with electrodes that apply an electrical current to cells of the stomach. In animal studies, they found that this stimulation boosted production of ghrelin, a hormone that stimulates appetite.

Traverso envisions that this type of treatment could potentially replace or complement some of the existing drugs used to prevent nausea and stimulate appetite in people with anorexia or cachexia (loss of body mass that can occur in patients with cancer or other chronic diseases). The researchers also hope to develop ways to stimulate production of GLP-1, a hormone that is used to help manage diabetes and promote weight loss.

“What this approach starts to do is potentially maximize our ability to treat disease without administering a new drug, but instead by simply modulating the body’s own systems through electrical stimulation,” Traverso says.

At MIT, Langer will help to develop nanoparticles for mRNA delivery, and Chandrakasan will work on ways to reduce energy consumption and miniaturize the electronic functions of the capsules, including secure communication, stimulation, and power generation.

The Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s portion of the project will be co-led by Traverso, Ameya Kirtane, Jason Li, and Peter Chai, who will amplify efforts on the formulation and stabilization of the mRNA nanoparticles, engineering of the ingestible devices, and running of clinical trials. At NYU, the effort will be led by assistant professor of bioengineering Khalil Ramadi SM ’16, PhD ’19, focusing on biological characterization of the effects of electrical stimulation. Researchers at the University of Colorado, led by Matthew Wynia and Eric G. Campbell of the CU Center for Bioethics and Humanities, will focus on exploring the ethical dimensions and public perceptions of these types of biomedical interventions.

“We felt like we had an opportunity here not only to do fundamental engineering science and early-stage clinical trials, but also to start to understand the data behind some of the ethical implications and public perceptions of these technologies through this broad collaboration,” Traverso says.

The project described here is supported by ARPA-H under award number D24AC00040-00. The content of this announcement does not necessarily represent the official views of the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health.

© Image: Courtesy of MechE